Every year thousands of Native Americans — dancers, singers and musicians — hit the powwow circuit that spans the U.S. and Canada.

The Denver March Pow Wow is Colorado’s largest springtime powwow and is even internationally known for drawing in the largest numbers of drum groups. The event celebrates its 45th anniversary starting Friday.

The Denver March Pow Wow sparked the interest of Centennial resident Angie Nofziger, who asked Colorado Wonders what the powwow was, and what happens there.

Grace Gillette, the executive director of the Denver March Pow Wow committee, said that traditional celebrations evolved and blended with those of other tribes into the event someone sees today.

“‘Powwow’ itself is a more contemporary term. They’re what we referred to as social gatherings, or celebrations and dances (that) were done for like the celebration of a marriage, the celebration of a birth, a name-giving ceremony,” Gillette said.

The Painful Backstory Behind Powwows

For centuries American Indian communities conducted ceremonial gatherings within their individual tribes. The designation of land as Indian territory — now known as reservations — alongside Native American treaties and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 are the ugly impetus that caused the pivot to and the rise of intertribal gatherings.

Families and tribes were separated, ripped from their land, forced to assimilate to European culture and killed in part of the efforts of colonizers to secure the nutrient-rich lands of what is now the east and the southeastern United States.

Gillette is a member of the Arikara tribe, or dead grass society members. Her father was one of the tail feather carriers, a sacred position. Her parents were deeply affected by the forced assimilation.

“I'm the generation where my parents were forced to go to school and they were punished for speaking their language,” Gillette said. “So English was always spoken in the home. It was to get away from your Indian ways. I did not dance as a young child. I got my Indian name and my right to dance when I was probably 40 years old.”

Thus powwows and intertribal gatherings became homecoming celebrations, where separated families and communities could reunite. They also became a way to preserve and pass down American Indian culture and tradition to younger generations.

Denver’s Powwow Scene Grows

Young natives in Denver seeking a deeper connection with their culture is one of the reasons the Denver March Pow Wow was born. Many Native Americans were drawn to the city through a ‘50s-era Bureau of Indian Affairs employment assistance program. Gillette herself came to Denver in the ‘70s through the program.

“The BIA gave you information about the community. That’s when I first went to the Indian Center, and they were having a weekend pow wow and I saw a lot of my relatives from home,” Gillette said.

She immersed herself in the community and became involved with the Youth Enrichment Program. Kids would raise money by putting on fashion shows and other fundraisers so they could go to a big powwow on one of the reservations in the summer. At the same time, many were also going through the ceremonial processes of getting their Indian names, their rights to wear feathers and regalia, and the tedious process of creating their own outfits.

Eventually, Denver Indian Center officials decided to host a powwow of their own. The event operated under the Indian Center until 1984, when it was formally incorporated as its own organization. The powwow quickly outgrew each of its event spaces, from the Indian Center ballroom to a gymnasium on the Auraria Campus to its current home, the Denver Coliseum.

Keeping The Powwow Holy

Before any celebration starts, Native Americans believe each gathering should begin with a blessing. Doug Goodfeather is the spiritual advisor for the Denver March Pow Wow and leads the ground blessing ceremony each year.

“We always begin with prayer. We were subjected to a lot. Our religion, our spiritual ways were outlawed and we just recently fought them and got it back in (the) 1978 Freedom of Religion Act,” Goodfeather said. “So it's really important that we always begin to gather people to put them in a conscious state of creating good energy and we lay that down on the grounds.”

The prayer ceremony that Goodfeather conducts for the Denver March Pow Wow happens the day before the event and lasts about an hour. The attendees gather in a circle and face west to begin the prayer. The west harnesses the power of the thunder people, who usher in ceremony, protection and healing, Goodfeather said.

He brings symbolic items to the prayer, including sage, water, a staff in a can of earth, and the hide and skull of a buffalo. At the end, he invokes his ancestors.

“We say ‘all my relatives,’” Goodfeather said. “Why we say that is because for hundreds of years, even thousands of years, we say Mitákuye Oyás’iŋ which means all my relations. And why we say that is everything that God has created on this earth is our relative.”

The Importance Of Drumming, Dance And Art

Drum, dance and art are the brick and mortar of any powwow.

Families often take part together, like Tanksi Clairmont, who said her family does. They are known in the Native American community as a dance family, but they also sing and drum.

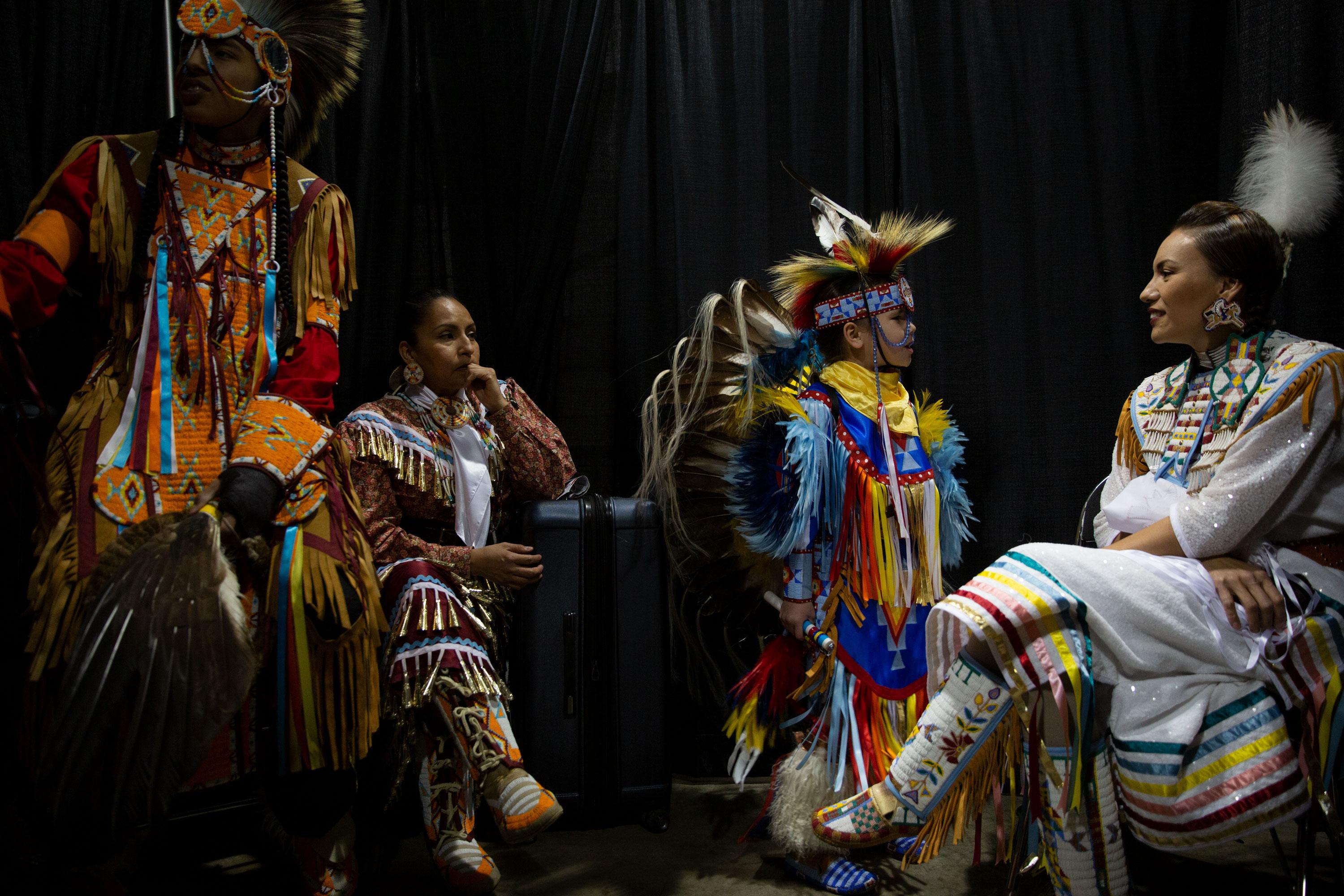

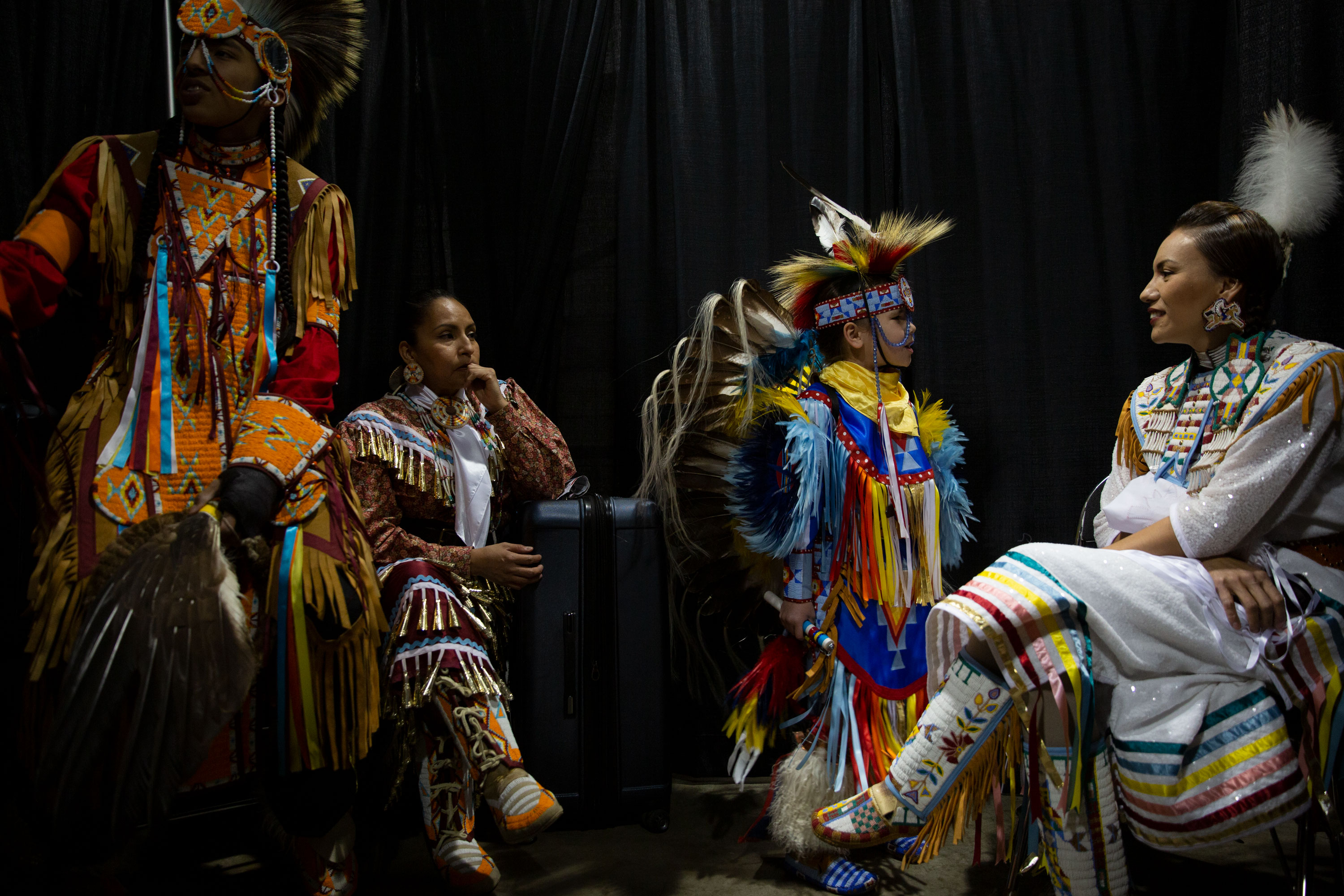

Clairmont handmakes all the clothing and regalia for her family. It’s intricate and time-consuming work: one piece can take a year to make, and stay in the family for generations.

Outfits can embody tradition, with vibrant reflections of tribal history and familial ties, while blending in modern trends and personal style.

“It's always ongoing,” Clairmont said. “There's never a time where I'm not thinking of sewing or beading or drawing out designs. So it just happens year round it's not just for a certain pow wow.”

There are many different styles of traditional Native American dance. Clairmont is a fancy shawl dancer, a newer style of dance developed about 40 years ago. Fancy shawl dancers, draped in a colorful fringed shawl adapted from a traditional women’s blanket, resemble butterflies in motion.

Clairmont’s mother and her twin aunt were some of the first fancy shawl dancers in the country.

“She's really the one who inspired me,” Clairmont said.

At a recent performance, Clairmont danced with four of her family members, including her teenage daughter and young son. Dance is a constant part of their lives: they dance in the house and invent new footwork in the kitchen every day.

Drum circles are integral to powwow performances. The Colorado Crew group from Denver will perform at the Pow Wow. The circle spans generations — some are barely school-aged, while others have drummed for nearly 50 years.

Greg Shortman, a Colorado Crew member from the Assiniboine tribe, said that preparing for a large, intertribal powwow such as Denver’s means practicing synchronized drumming and singing. The group has to brush up on the many songs they may be asked to play. One is the flag song.

“You’ll always hear that at pow wows... It's equivalent to the national anthem of the United States. So each tribe reservation has their own flag song,” Shortman said.

Each song is different, from the drumming technique to whether it has words or not. When there aren’t words, which happens when a song is written in the language of a tribe that not every drummer can speak, sounds called vocables are a substitute.

Shortman said the drum group is a way to feel fellowship for the community.

“Here in Denver (it) is an aspect of community building, where all of these different tribes of people come together and we learn each other's songs to sing at powwows,” he said. “We eat. Have, like a potluck. And so we all get the fellowship visit catch up with each other.”

These practice sessions, like many events in Denver’s Native American community, happen at the Denver Indian Center. Tom Allen, a member of the Sac and Fox and the Northern Arapaho tribes, said it’s also the place where many elders meetup to create pieces of art they sell at the Pow Wow.

Allen, like his father before him, works at the center, and he’s been creating beadwork since he was a young boy.

“Beadwork is a expression of a Native American, I think, ingenuity and creativity,” Allen said. “I know when my father taught me to bead, he said there should be some kind of imperfection in it. ‘Cause we believe there's a spirit in what we make, and the imperfection is where that spirit will come out of it.”

The Denver March Pow Wow now draws participants from 95 tribes in 35 states and Canada. More than 50,000 people attended last year.

Grace Gillette, the organizer, said the hardest part of her job these days is keeping the powwow running the way a powwow should be run.

“We're not here for entertainment,” Gillette said. “It's not a show. We're sharing our culture through song and dance.”

The Denver March Pow Wow runs from March 22-24, 2019 at the Denver Coliseum.