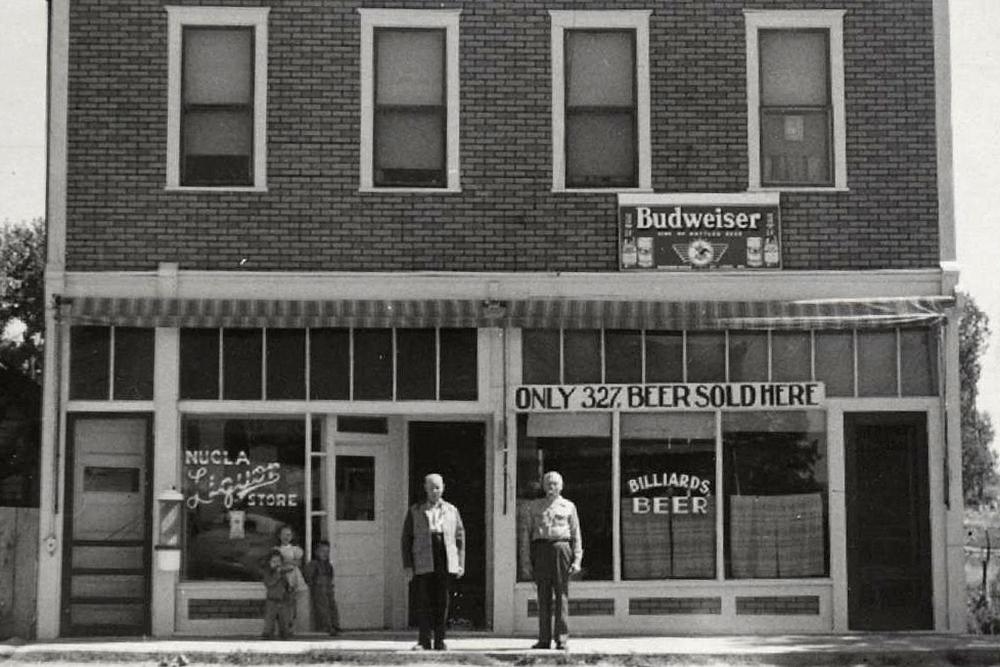

Even during its boom times, the high desert community of Nucla has always been a small place.

It’s also been a beloved one, drawing and keeping people in search of different kinds of lives.

Marie Templeton’s father was one of them, moving his family to the area toward the beginning of World War II.

And Templeton, 89, would like to bust a misconception you may have about this remote corner of Montrose County. Even though it was once a well-known hub for uranium mining, its name has nothing to do with nuclear energy.

“Nucla was supposed to be the nucleus of this socialist bunch of people,” Templeton said.

That idealist bunch was the Colorado Cooperative Company, which Templeton spent years studying as a historian with the Rimrocker Historical Society. The CCC was a utopian society that sprang out of an economic depression known as the Panic of 1893, and one of several such communities that dotted Colorado in the 1800s. It offered the promise of a new life, one where everyone got the same fair shake and did the same hard work, all in a place far from everything they’d ever known.

When asked about the soul of Nucla, Templeton grinned with pride.

“Persistent is the best word I can think of,” she replied.

They had to be, she said, in order to dig Nucla’s famed 17-mile irrigation ditch, a project that took 10 years. In its early days, the town had a reputation for hard work, but also for music and art. Around the turn of the century, the area’s old newspaper, The Alturian, reported that locals held lively dances three times a week.

After only a few years, however, the collective broke up over fights about how equally the work was really shared. In particular, there was tension between the town’s founders, people who had actually dug the area’s famed ditch, and newcomers, who hadn’t had to put that sweat into the land.

After the discovery of radium in 1912, many residents transferred their can-do spirit from farming to mining.

“We’re going to do it, and we’re going to do it!” Templeton said, in a gleeful impersonation. “And that’s it!”

By the time she and her family moved to neighboring Uravan in the early 1940s, the area was well on its way to becoming an important part of America’s march toward atomic weapons.

That meant jobs for locals.

“And these guys had been living poor all their life, and they finally had a good way to support their families,” Templeton said. “And so they worked in the uranium mines.”

With a few hiccups over the years, Nucla’s boom times would last through the 1970s — a radioactive gold rush.

Jerry Nelson, 60, remembers the promise of this place.

“I personally knew some guys walking around in bib overalls that were millionaires,” he said.

While their fortunes didn’t seem to change those guys, Nelson said the money uranium mining brought to town sure did affect this tight-knit community. When he graduated from high school in the late ’70s, Nucla was busy. There was always a dance or a baseball game to go to. While the closest movie theater now is about two hours away, Nucla and neighboring Naturia used to be home to a cinema and The Uranium Drive-In.

When young people say there’s nothing to do in Nucla these days, Nelson likes to tell them the same thing.

“On a Saturday night when I was in school, it was bumper-to-bumper on Main,” he said. “You got off Main, you had to wait for a buddy to let you back on.”

Consistently, kids nowadays don’t believe him.

“Yes, it was,” he’ll tell the young disbelievers. “It was wild.”

Those wild times in Nucla came to an end with a disaster 2,000 miles away, 1979’s partial meltdown and radiation leak at Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania. Uranium prices plunged. Nucla’s mine closed.

Hank Nelson, Jerry’s cousin, said it was a loss some here never accepted.

“My granddad, up until his dying days, was waiting for the price of uranium to go up so he could get back to mining,” he said, recalling conversations between the two of them.

“Grandpa, you're tethered to an oxygen tank, you're 77 years old,” Nelson would say.

“That's all right,” his grandfather would reply. “I'll be ready.”

That fondness for uranium is common here. Chunks of it used to fall off trucks all the time, said Templeton. She remembers showing the ores to a few of her husband’s family members years ago.

“So I saw a little piece of yellow, about as big as my finger, on the ground when we were walking around, and I just picked it up and said, ‘There’s a piece of Uranium,’” Templeton said, before starting to laugh. “That woman almost fainted. ‘Ooh! Don’t get it close to me!’”

Templeton talks about the element with more nostalgia than fear, even though her husband and father both died of cancer after working in the mines.

“They all knew that there was a risk. But they were supporting their families. They were making good money,” she said.

No one’s seen that kind of money around here in years. Nucla’s probably most famous now for requiring heads of households to own a gun. The policy isn’t enforced, but it shows the town hasn’t lost its taste for unconventional politics.

Today, as it faces the loss of its power plant and the coal mine that supplied it, Templeton still has faith in this place, a rugged town that’s far from everywhere and on the road to pretty much nowhere.

“I have no doubt we will survive,” she said.

She sees a place that’s already been persevering for generations, thanks to the same kind of hearty, dedicated folks who founded it.

Outside the window, her sprinklers were going, using water that still comes from the ditch built by the Colorado Cooperative Company, more than a century ago.

“History repeats itself. I know that,” Templeton said, “Don’t you?”