There’s beauty in the mundanity of David Thompson’s life. The 65-year-old works out at the Y, where he likes to ride the stationary bike; dotes on his grandsons, Jackson and Ethan; and walks the dog. He has a 14-year-old Shih Tzu named Gracie.

“She does tricks,” Thompson said. “I taught her how to do a 360 with a treat. She spins around on her back legs.”

The basketball legend nicknamed “Skywalker” for his otherworldly leaping ability will celebrate 31 years of sobriety in December. The man who Michael Jordan idolized has long been at peace since cocaine, alcohol and injuries sunk him into a pit of despair.

“I was stuck in that pity pot for a long time regretting what I’ve done and what my life was,” Thompson said. “If you stay there, you won’t grow. You have to pull yourself up and continue to grow and continue to live.”

Over the last three decades, Thompson has learned from the past but not been so damaged by it that he has allowed it to poison his present.

“That’s the only way you can recover,” Thompson said. “First you have to forgive yourself.”

Before addiction sapped his ability, Thompson helped us realize what was possible on the basketball court. He is credited with popularizing the alley oop. As a rookie with the Nuggets, he went toe to toe with Julius Erving in the first-ever Slam Dunk Contest. He once scored 73 points in an NBA game. Shortly thereafter, he signed a then-record $4 million contract.

The runway to that ascent was a dirt court where Thompson first learned to love the game. Thompson grew up as the youngest of 11 children in Boiling Springs, North Carolina, in a house that lacked indoor plumbing. Friends and family members converged there to play on the unpaved court out back. The rims were bicycle wheels with the spokes removed.

“No nets or anything,” said Thompson’s cousin Alvin Gentry, who was a regular on that court and now coaches the New Orleans Pelicans. “We’d go out there and play all day after church.”

Thompson was a 5-foot-8 eighth grader when he dunked a basketball for the first time. He knew he had God-given gifts, and he made sure to maximize them. He wore ankle weights when he trained, and he was constantly coming up with different series of jumping regimens. By 10th grade, he could stand in front of the basket, pogo stick straight up and touch his elbow to the rim 10 times in a row.

His 42-inch vertical leap landed him in the Guinness Book of World Records as a freshman at North Carolina State. That year, he also was on the finishing end of an alley oop for the first time, which like Post-it notes and penicillin was a happy accident. During practice, Thompson was getting overplayed by his defender. He cut toward the basket, wrangled a lob pass from point guard Monte Towe and dropped it in the orange cylinder mid-flight.

“Coach (Norman) Sloan stopped practice,” Thompson said. “He said, ‘Hey, I like that. Maybe we can put that in our offense.’ Smart coach he was.”

Dunking was banned in college at the time, so Thompson wasn’t able to punctuate those lob passes as authoritatively as he would’ve liked.

“I’ve always thought that one of the biggest tragedies of college basketball is there was no dunking when David Thompson played college basketball,” said Towe, who within weeks of playing alongside Thompson at North Carolina State wrote home to tell his parents in Indiana he had a teammate who was better than local legend Oscar Robertson.

On March 23, 1974, Thompson, with 15 stitches in his head, the result of a nasty spill he suffered the week before, led Towe and the rest of the team against UCLA in the NCAA Tournament semifinals. UCLA had won seven national titles in a row. Thompson scored 28 points, and the Wolfpack won. Two days later, he poured in 21 points as North Carolina State earned its first national championship in school history.

“David Thompson is barely bigger than my wife, Lori, and she’s 5-foot-3 and weighs 100 pounds,” Bill Walton, who starred for UCLA in the early ‘70s, told CPR. (At 6-foot-4, Thompson is not quite as small as Lori but is nowhere near the 6-foot-11 Walton.) “And David Thompson, in a game dominated by the winners of the genetic lottery, could get wherever he wanted to go.”

Walton still considers the loss to North Carolina State the most disappointing defeat of his career. “It is a stigma on my soul, and there’s no way I can get rid of it,” he told NCAA.com in 2015. But when Walton was approached to write the foreword for Thompson’s book in 2003, he didn’t think twice.

“The way he would soar through the air and elicit the incredible awestruck gasp of the audience; they had never seen anything like this,” Walton said. “It was super fun to be a part of that. Much more fun to be on the winning side, I’m sure. But I’m honored to be in his historical shadow.”

Thompson was at the height of his powers during the 1973-74 season. He averaged 26 points on 54.7% shooting, led North Carolina State to a 30-1 record and earned Most Outstanding Player honors at the NCAA Tournament. There were no indications then of the fall to come.

“Life is easy when you’re hot,” Walton wrote in Thompson’s biography, “Skywalker.” “David’s story is what you do when the ball bounces the other way.”

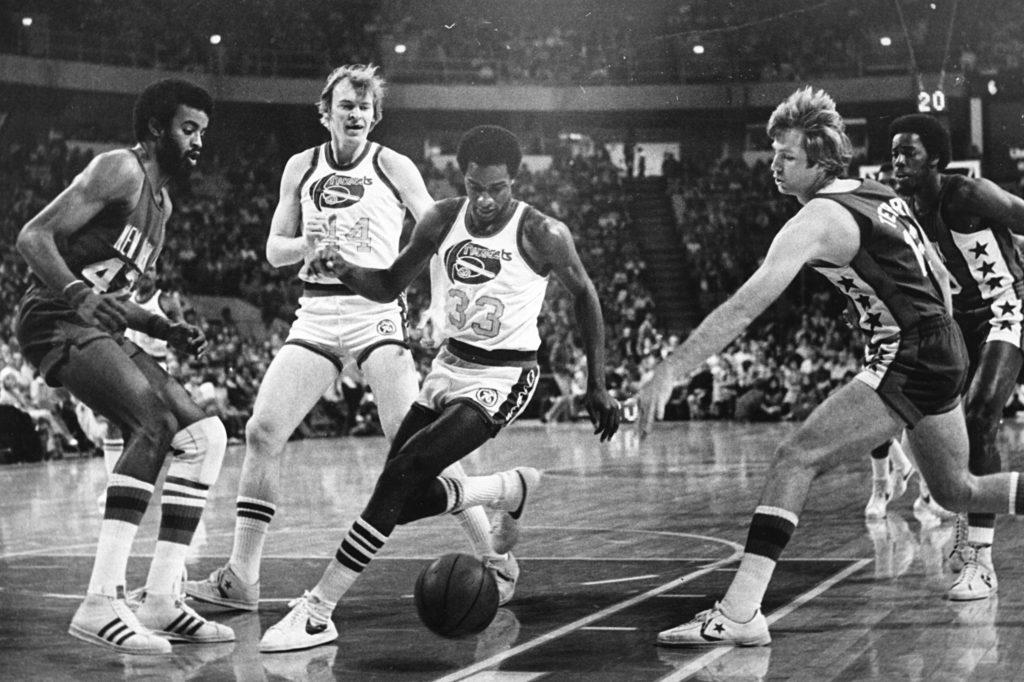

The Skywalker nickname began to stick during Thompson’s rookie season in Denver. CBS broadcaster Brent Musburger, who coined it, was inspired by the way Thompson crossed his legs as he soared through the air.

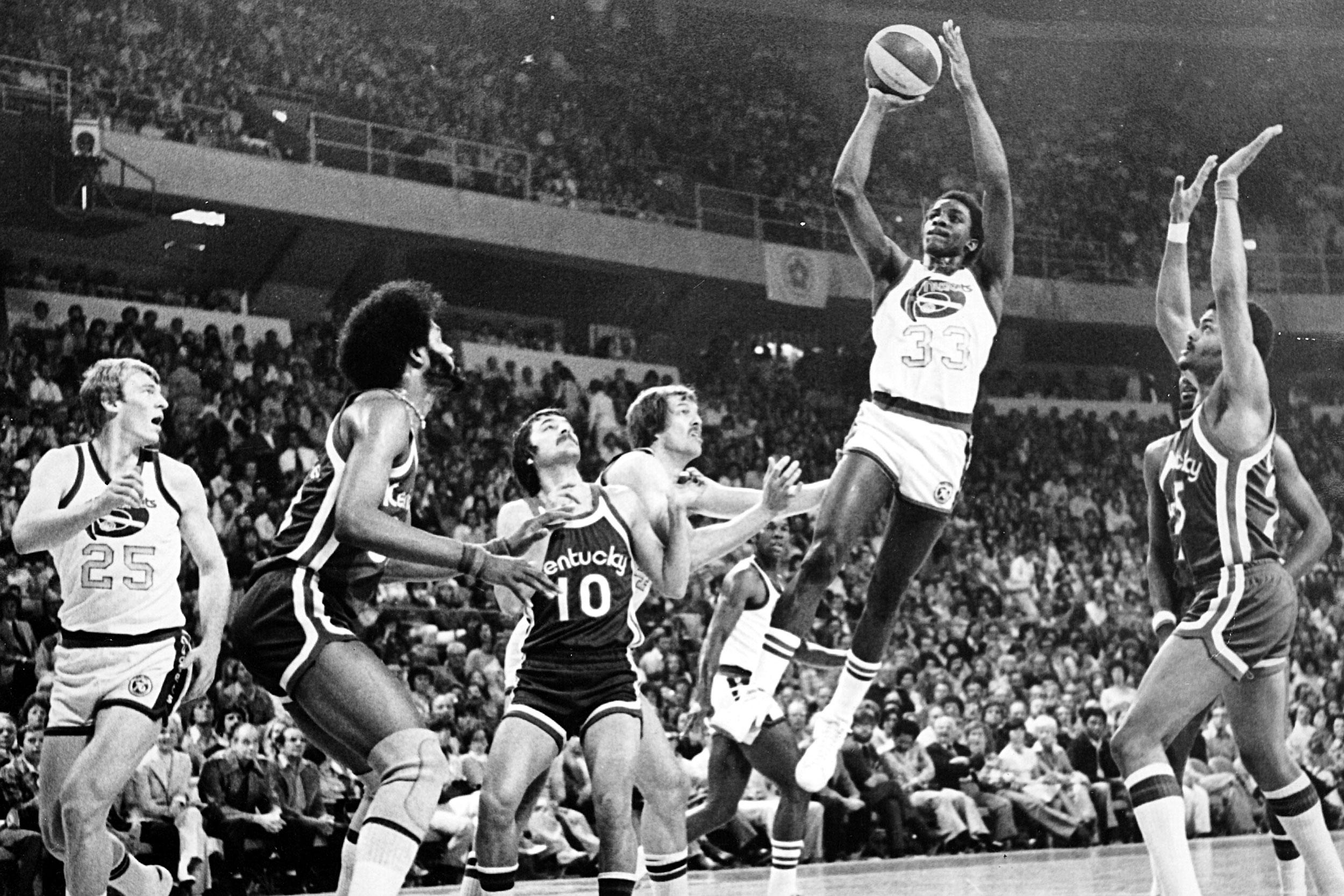

Thompson ended up in Denver, which was then part of the ABA, after spurning the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks, who took him No. 1 overall in 1975. He was instantly one of the league’s biggest draws. He averaged 26 points, 6.3 rebounds and 3.7 assists as a rookie. Prior to the All-Star Game, he faced Erving in the inaugural Slam Dunk Contest, which was the brainchild of former Nuggets executive Carl Scheer. Thompson threw down a two-handed 360, but Erving famously won it when he dunked from the free throw line.

“Dr. J marked off his steps and took off running,” Thompson recalled. “He had the short shorts and the big old afro. He took off running, and his afro was blowing in the wind. He dunked from the free throw line, and everybody went crazy. I came in second.”

The Nuggets finished the regular season 60-24, the best record in the ABA. They earned a first-round bye, then knocked off the Kentucky Colonels in seven games to reach the championship round against Erving’s New York Nets. Thompson played well in that first, and though he wouldn’t know it then, only Finals appearance of his professional career, but Erving was better. The Nets beat the Nuggets four games to two.

The 1976 Finals marked the end of play in the ABA — later that year, both teams joined the NBA as part of the merger — but they marked the beginning of something else. During the Finals, Thompson first tried cocaine.

Thompson had been searching for a pick-me-up after playing in more than 100 games as a rookie, so he turned to a drug that was on its way to becoming ubiquitous in professional basketball. Cocaine offered an energy boost, Thompson learned. It would take years before Thompson found out everything else that comes with it.

On April 17, 1978, Thompson agreed to a contract extension with the Nuggets that made him the highest-paid player in NBA history. The deal, which came a little more than a week after Thompson scored 73 points in Denver’s final game of the regular season, was worth $4 million over five years.

At first, it felt like a blessing. How could it not? A kid from Small Town, North Carolina, had struck it rich doing what he loved. But as time went by, those seven figures started to symbolize something else.

“I was excited about it,” Thompson. “But I didn’t realize how everybody was going to look at it. After I signed that contract, I was no longer David Thompson. I was David Thompson, the highest-paid player. David Thompson, the $4 million man.”

The 1979-80 season was a disaster. Thompson appeared in only 39 games as he dealt with plantar fasciitis, an inflammation of the tissue that connects the heel to the toes. Sidelined for much of the season, Thompson’s cocaine use went from an occasional boost to a daily habit. Thompson began to realize he had a problem. He arrived late to practices. He missed team flights. He grew more distant.

“Sometimes the pressures of being a superstar or whatever, sometimes you fall back on some vices,” Thompson said. “Drinking and using, sometimes it would get out of hand, and that’s exactly what happened to me.”

Thompson loved basketball but not the fame that came with it. At times, he felt uncomfortable in the public eye.

“I think that was part of the downfall when he went through the tough times, said Gentry, who’s coached superstars such as Steve Nash and Anthony Davis. “He never asked to be this star person. He just wanted to be a great basketball player.

“I think everyone thinks that it would be something great, but when it actually happens to you, you understand there is no privacy and everybody thinks that they own a piece of you.”

In December 1979, Thompson resigned as co-captain. The Nuggets limped to a 30-52 record and missed the playoffs.

“When the team doesn’t do as well, you’ve always got to blame somebody,” Thompson said. “You making all the money, and the pressure started building.”

Things got so bad that his wife, Cathy, went to the police and asked them to arrest her husband’s drug dealer. She wanted her husband to stop using.

By the 1981-82 season, Thompson, who at 27 years old should have been entering his prime, lost his starting spot and began coming off the bench. His numbers fell off a cliff. He averaged 14.9 points after never contributing fewer than 21.5 per game in his first six seasons. Displeased with a reduced role, Thompson asked for a trade.

The Seattle SuperSonics decided to gamble on a player who only four years earlier had scored more points in a single game than any player not named Wilt Chamberlain. On June 16, 1982, as it became clear Thompson was on his way out of town, the Denver Post ran a series of stories detailing Thompson’s addiction.

“Nugget Star’s Use of Cocaine Disclosed,” the newspaper’s above-the-fold headline on A1 read.

Two of the game’s greatest high flyers became forever intertwined at the first Slam Dunk Contest. Eleven years later, Thompson and Erving found themselves a million miles apart.

In April 1987, Thompson involuntarily checked into the North Rehabilitation Center in Seattle. By that time, he’d squandered his money. His basketball career was over. The death knell was a gruesome knee injury he suffered falling down the staircase of Studio 54. He had recently been arrested for shoving his wife in a domestic dispute and was sentenced to 180 days in jail. Thompson ended up at the detention and rehab center instead of jail after the pastor of a local megachurch, Doug Murren, went to bat for him in front of a judge.

Meanwhile, Erving was wrapping up one of the most celebrated careers in professional basketball history. At halftime of his final game in Philadelphia, Erving walked out to the court where he was honored in front of the home crowd and asked to reflect on his 16-year career. The broadcaster interviewing Erving asked who his toughest opponents were. The first name out of his mouth? David Thompson.

Thompson watched this unfold with about 30 other patients inside the game room at the rehab facility. The entire room broke out in applause as Erving mentioned his old rival.

“It kind of hit home and really helped me turn myself around,” Thompson said. “He was on TV, and here I was in jail going through this situation. That kind of helped me as far as me wanting to get my life back on track. You kind of realize that you’ve got self worth.”

In that moment, Thompson took his first steps toward ending the cycle that cost him his career and fortune. Erving’s shoutout awakened some long-dormant part of him that made him realize who he was before alcohol and cocaine transformed him. It also stoked something inside of him that helped him imagine who he could become without his vices.

“It made me want to prove myself,” Thompson said, “and I was able to do that.”

Thompson was determined to stop allowing his mistakes to compound. He stayed for two months at North Rehabilitation Center, then completed the rest of his sentence at Issaquah City Jail. Inside, he cracked open the Bible and rediscovered the Christian faith he’d abandoned.

After so many years in a downward spiral, Thompson was finally ready to heal.

This past February, the NBA held its All-Star Game in Thompson’s home state for the second time since the event began in 1951. There, in Charlotte, the Nuggets’ past, present and future shook hands. Thompson made an appearance to judge the Slam Dunk Contest, while Denver’s current franchise center, Nikola Jokic, was there to play in the first All-Star Game of his career.

Thompson owns a Jokic jersey, and he occasionally wears it around town, which is fitting because though their games couldn’t be more different, ground-bound Jokic is arguably the most talented Nugget since Skywalker. In May, Jokic became the first Denver player to make the All-NBA First Team since Thompson did it in 1978. Jokic wasn’t even born until 1995, but he’s aware of what Thompson was capable of in his heyday.

“Michael Jordan before Michael Jordan came around,” Jokic has said.

The idea of Thompson as a Jordan prototype is widely accepted in basketball circles. Jordan, who grew up in Wilmington, North Carolina, and was 11 years old when Thompson’s North Carolina State team won the NCAA title, has many times cited Thompson as one of his biggest inspirations. In 2009, Jordan asked Thompson to present him as he was inducted into the Hall of Fame.

“I was in love with David Thompson,” Jordan said during his 2009 speech. “Not just for the game of basketball but in terms of what he represented. We all go through our trials and tribulations, and he did. And I was inspired by him.”

Around the time Jordan became basketball’s biggest star in the early ‘90s, Thompson was looking for work. He’d gotten out of jail and moved back home, searching for a fresh start. George Shinn, the owner of the NBA expansion team the Charlotte Hornets, brought him on in the community relations department. Thompson’s job was simple: Share his story.

“It really gave me a chance to turn my life around,” Thompson said. “It gave me some hope.”

In 1991, Thompson reconciled with Cathy, whom he’d been separated from for the previous four years. She and their two daughters, Brooke and Erika, moved from Seattle to Charlotte, where the family reunited. Thompson and his wife remained happily married until 2016, when Cathy died after a battle with diabetes and resulting kidney complications.

“She was really the true love of my life,” Thompson said. “Me and my wife got married out in Colorado. Had our kids out in Colorado. When we first got out there, we were really just kids. We grew up a lot over the years. We were able to make a good life back in North Carolina.”

The Thompsons had a golden retriever and a black lab when they lived in Colorado. They got Gracie when they returned to North Carolina.

“She’s getting old,” Thompson said. “But she’s still active and barks a lot.”

These days, Thompson likes to keep a low profile. He still does the occasional speaking engagement, and in July, he traveled to remote Avery County to instruct at a basketball camp put on by his North Carolina State teammate Tommy Burleson. But for the most part, Thompson prefers to blend in.

“He can just be who he is,” Gentry said. “And it’s kind of funny because the people who are really deep basketball people, they still know who he is and how great he is, but he doesn’t have to live it every day. Doesn’t have to walk on the street and everybody is stopping him and doing this and doing that. I think it’s really good.”

Thompson doesn’t shy away from discussing his past; he’d just rather live in the present. Any bitterness has now dissolved into acceptance. Questions about what could have been no longer gnaw at him.

“I don’t regret the past,” Thompson said. “I’ve learned from the past. You can’t do anything about it. I’m happy with my career. I did something that very few people ever did. I had a good career, and it could’ve been better, but it wasn’t. I’m still considered one of the top 100 players in the history of basketball. Some people consider me the best player to ever play in the ACC. I did some good things. It could have been better. It doesn’t really bother me. I’m OK with it. I’m OK with it now.”

Editor's Note: An earlier version of this story misidentified the first name of Charlotte Hornets' owner George Shinn. The story has been corrected.