After you take care of business and push the handle on your toilet, it’s out of sight, out of mind, right?

But when the pandemic started, some folks, like Pieter Van Ry, realized there’s actually gold in that stuff.

“How it began was I actually, on a Sunday morning, woke up and I read a Popular Mechanics article,” he said. This was early on, March 2020, when the first wave of COVID-19 infections hit. “At the end of that article, it said, ‘If you have a wastewater facility and you're interested in participating in this study, please contact us.’”

As a matter of a fact, he did happen to have a wastewater facility.

Van Ry directs South Platte Renew. Its Englewood treatment plant serves 300,000 people southwest of Denver. That article Van Ry read had a catchy title: How Poop Offers Hints About The Spread of Coronavirus.

To see just how, I took a visit to the South Platte facility. On a snowy February afternoon, they opened a hatch down to a dark stream where the effluent flows into the plant.

“So this is essentially where it comes in,” Van Ry said, motioning to where big pipes meet down more than dozen feet below “one from essentially Englewood, one from Littleton.”

Let’s just say the odor did not carry the delightful fragrance of a dozen roses.

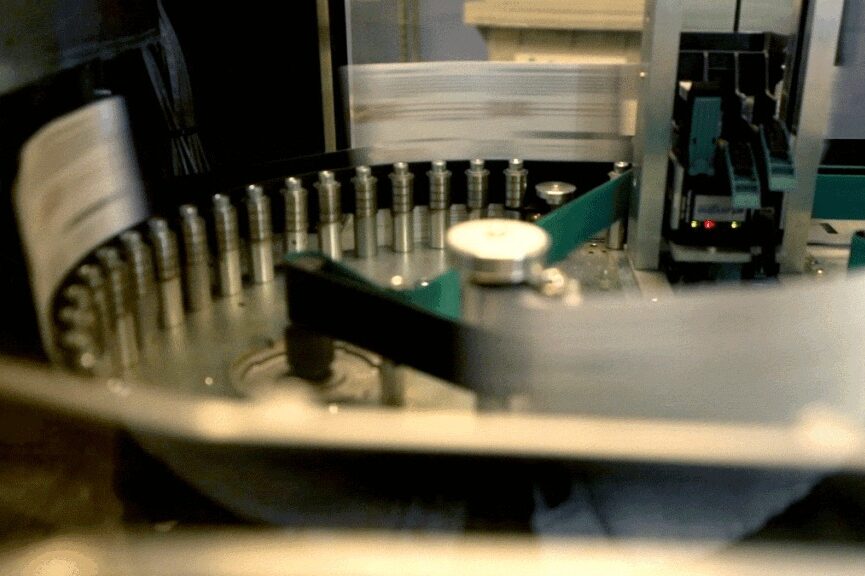

Van Ry’s colleague, lead operator Brandon Hinkhouse showed a machine siphoning off fluid through piping into a white plastic container.

“It grabs a sample and then purges it again and then it'll actually take a sample and that's what we collect,” he said.

The South Platte team sends those wastewater samples to a lab at a Massachusetts company called Biobot Analytics. Its mission: “population health analytics powered by sewage.”

How the testing works

From the start, lab results from the samples showed exactly what the virus was doing, Van Ry said. The team at South Platte Renew had stumbled onto a powerful new public health tool: testing wastewater to monitor, wave by wave, the spread of a virus.

“Really what it tells me, it was spreading rapidly through the community,” Van Ry said.

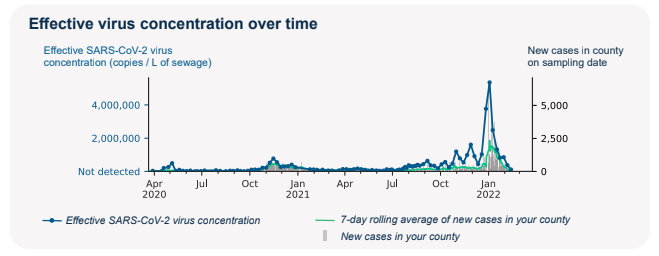

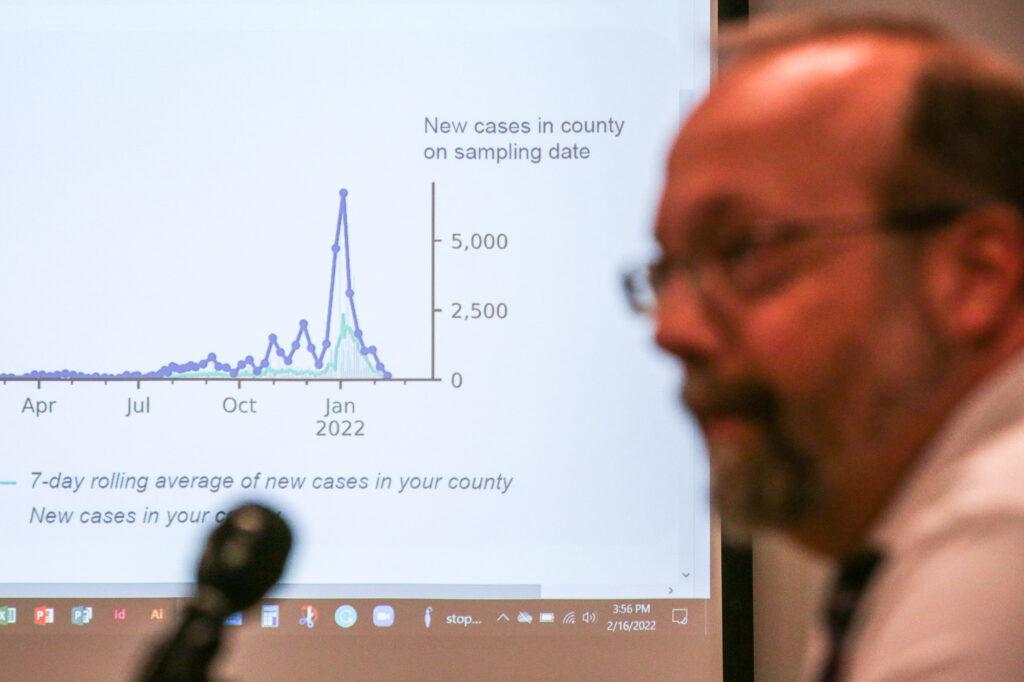

In a conference room, he showed a slide of data from samples. All the surges were clear, alpha, delta and then a spectacular spike driven by a new variant in early 2022.

“With omicon being so, so transmissible, the fact that the chart went so high, we had to readjust the scale,” to accommodate for what the samples were showing, he said.

The technique caught on around Colorado and the country. Colorado Mesa University’s program, in collaboration with the Broad Institute of M.I.T. and Harvard, generated national coverage via a story in the New York Times.

Now the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is aiming to expand wastewater testing with the National Wastewater Surveillance System.

And Colorado is doing the same.

Over at the state lab in Denver, techs in white lab coats, wearing masks, draw out liquid samples with pipettes.

“The samples come in here and they start their initial processing,” said lab director Emily Travanty, as she gave a tour around the facility. “They get concentrated and filtered and then they go on to the detection and then the sequencing.”

People infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, shed viral RNA, genetic material from the virus, in their feces. In wastewater tests, scientists use that RNA to tell what’s there. Travanty said the state health department, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE), started doing this five years ago with routine testing of food borne illnesses, like salmonella.

“So we were able to pivot that expertise towards COVID-19 as the pandemic emerged and build upon that expertise within the laboratory,” she said.

Effort could expand across Colorado

The agency is now working with 33 wastewater utilities and adding as many as seven more utilities by the end of February. Its goal is statewide coverage.

The state compiles the data from a variety of sites on a public dashboard. It also shares its numbers with the CDC. About $9.4 million in federal funds is paying for the state’s wastewater testing project from January 2021 through at least July 2023. The total includes personnel, supplies, equipment, and contracts.

Travanty’s colleague, epidemiologist Rachel Jervis, noted that with clinical coronavirus tests, someone needs to seek medical care, get tested, and then get results.

“Whereas with COVID wastewater, we found that up to 50 percent of people will shed COVID virus in their stool regardless of whether or not they have symptoms,” she said. “So we're sort of removing the human behavior component of seeking medical care.”

Along with normal testing, it gives an early look, an early warning sign about where COVID spread is highest.

“Essentially we're looking at trends. We rarely use a single sample to infer much about our COVID wastewater data. We’re looking at trends across several samples,” Jervis said.

“It's a blunt instrument in some sense, right? You're able to say that, ‘Yeah, there seems to be a lot of virus in this location at this time,’” said Jude Bayham, an assistant professor at Colorado State University and in the Colorado School of Public Health, who is also, who is also a member of the state’s COVID-19 modeling team.

Bayham said as overall COVID-19 trends improve and Colorado pivots to the next phase — and maybe scales down other testing — still-evolving wastewater analysis promises to step up.

“Wastewater surveillance is a relatively cheap alternative that can provide a lot of information,” he said.

That kind of information can guide coronavirus response.

Seeing COVID in poop led to action at University of Denver

At the University of Denver, outside a red-bricked dorm, some folks with the school's response team recently cracked open a heavy steel manhole lid.

Down below, a steady stream of wastewater flowed.

“That's sewage right now. Well, it's everything right now,” said Keith Miller, an associate professor in chemistry and biochemistry at DU. “It's heavy load, right? They’re taking showers right now. So there isn't a lot of solids.”

In fall 2020, the first weeks of the in-person school year, DU’s team started pulling samples from pipes like this.

Mechanical engineer Corinne Lengsfeld oversees the campus’ saliva testing lab. She said a wastewater sample taken on one Friday early that semester was off the charts. “It was a million virus units per one liter,” she said. “Holy Toledo!”

That information convinced school officials to have everyone in the dorm do rapid nasal testing. “That's what wastewater testing is, it's the one that's gonna give you the biggest picture first,” Miller said.

Using the wastewater data, plus following up with quick testing, allowed them, over the weekend, to identify 10 infectious students and move them to an isolation dorm. Lengsfeld said that without that, perhaps 100 more students in the dorm of 300 might have caught it. “It works. I mean, it definitely is a case study, I think, of exactly how to control spread,” she said.

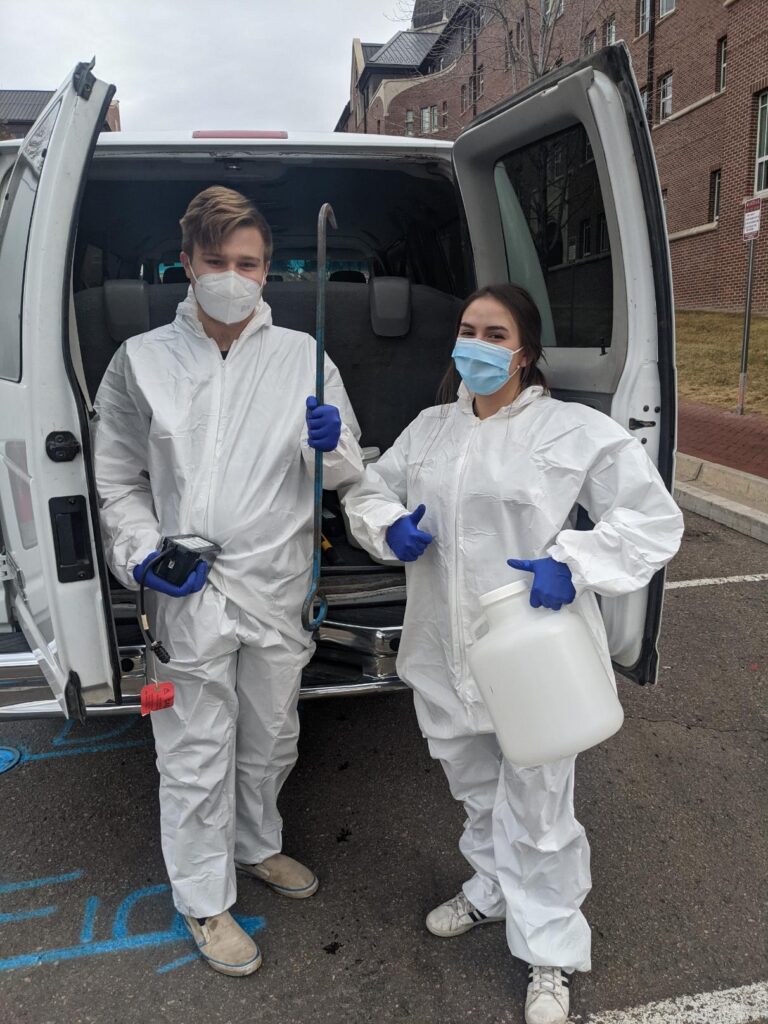

Student Vander Georgeff volunteered to put on PPE and climb down into pipes below campus to gather plastic containers collecting the muck. It was not what he expected to be doing his freshman year.

“It got pretty gross at times,” he said with a laugh. “We never envisioned walking around in white Tyvek suits at six in the morning pulling these, they looked like those Gatorade coolers, those big round ones, pulling those things out of sewer drains.”

He said he learned a lot from “playing with poop,” as they jokingly called it. He said prior to vaccines being available, and more widespread spit testing, it helped keep the campus safer, giving DU a tool to detect cases and drive overall numbers lower.

Now he works in DU’s molecular diagnostics lab. “I could definitely see myself continuing in this career,” Georgeff said.

How testing wastewater will help in the future

Back at Platte Valley, Pieter Van Ry also takes pride in his team’s work. Treatment plants like this have generally been unheralded, doing a key job no one wants to think about, and often the butt of wisecracks.

“Yeah, your number two is our number one,” he said. “There’s a lot of good ones out there.”

But now there’s a new lofty priority: to be a sentinel of coming contagion. And not just for COVID-19. Eventually, it could be used to spot other diseases too.

“It could be one of those things that does become somewhat of a game changer in terms of understanding community health,” Van Ry said.

“We are really excited about this new tool,” said Dr. Rachel Herlihy, the state’s epidemiologist. “It will help us understand regional differences. It's also been incredibly useful for us in understanding the emergence of new variants.”

“We're still really figuring out how to best put it to use,” Herlihy added.

A top official with the CDC sees it that way too, telling reporters in a recent conference call that the agency anticipates using the system for infectious diseases and other things.

“One of the strengths of wastewater surveillance is that it is very flexible,” said CDC microbiologist Dr. Amy Kirby, team lead for the National Wastewater Surveillance System. “So once we have built this infrastructure to collect the samples, get them to a laboratory, get the data to CDC, we can add tests for new pathogens fairly quickly.”

Should a new pathogen of interest pop up, she said, they could ramp up this system within a few weeks to start gathering community level data on it.

The agency expects to be able to use the system to target other pathogens, like antibiotic resistance, foodborne infections, like E. Coli, salmonella, norovirus influenza and an emerging fungal organism that causes disease, called Candida auris.

There is also interest, down the road, in using it for noninfectious diseases, like tracking substances of abuse, Kirby said.

While the approach is groundbreaking in the U.S., it’s been used for years elsewhere.

“Wastewater surveillance has been used for many decades, actually, to track polio in communities, not in the U.S., but definitely overseas as part of the polio eradication efforts,” Kirby said. “And they use it essentially the same way we do – so to look for communities where polio is circulating and then use that as a trigger for additional clinical surveillance in those communities.”