Whether this is the first presidential election you plan to vote in or not, you may have questions about how your ballot travels from your home to your local county election office, and what happens when it gets there.

We tackled this question with a comprehensive breakdown back in 2022, but here’s an abridged version.

Step 1: Cast your ballot

In Colorado, all registered voters are mailed a ballot. Voters can choose to vote by mail, take their ballot to an official drop box or vote in person.

Step 2: Ballot collection

Together, a pair of election workers — a Republican and a Democrat — will unlock the box and unload all of the ballots by hand. They fill out a log of how many ballots they’re picking up and put them all into an official transit box that is locked.

On Election Day, teams retrieve paper ballots from in-person polling places in a similar fashion.

When they get back to your county clerk’s office, workers then unlock the box and unload the ballots.

Step 3: Ballot verification

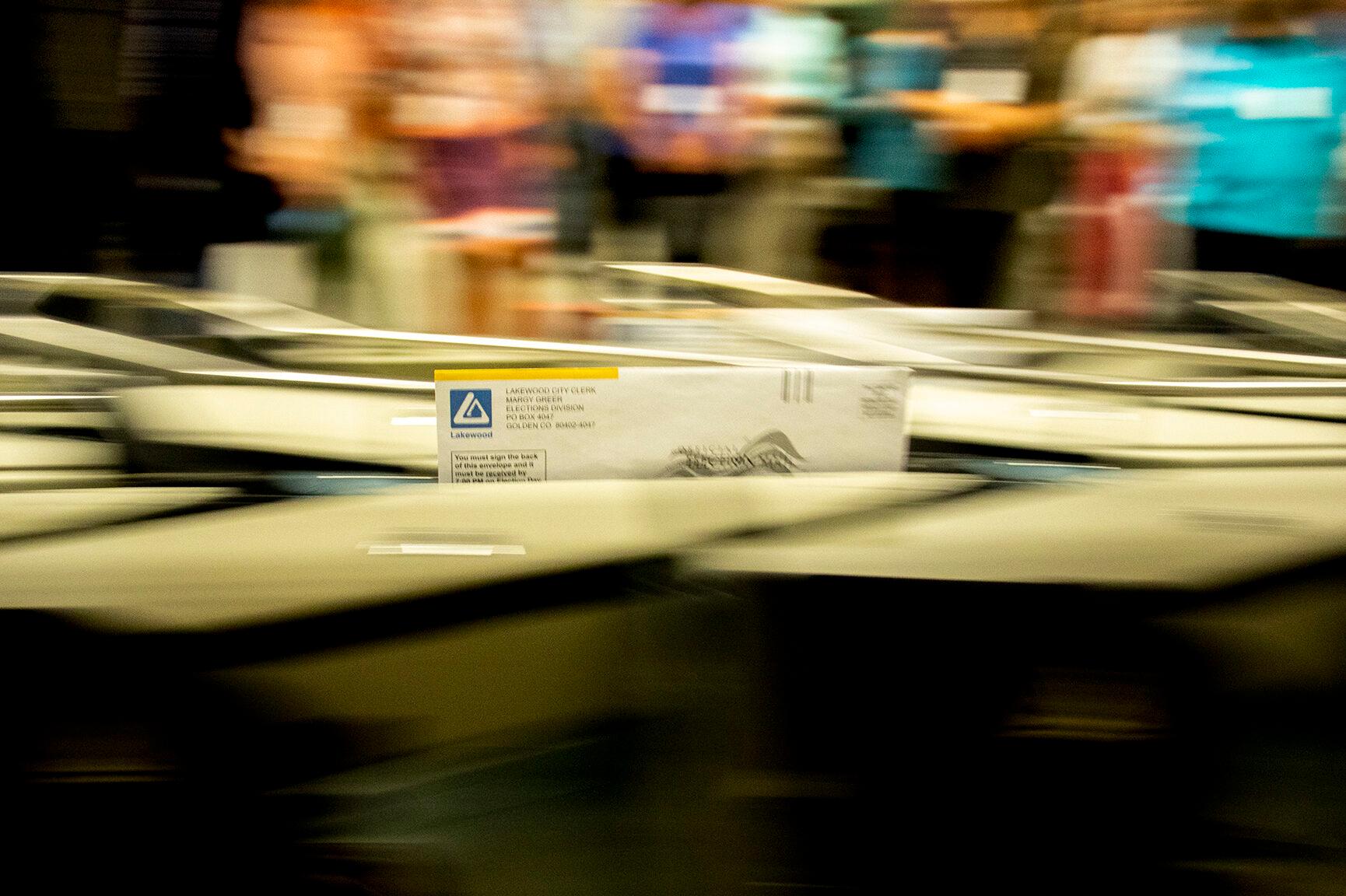

Next, your county will verify your ballot's authenticity using two things on the outside of the envelope: your signature and a printed barcode.

Depending on how big your county is, the process takes place by hand or with a special ballot sorting and scanning machine.

At the same time, a signature-verification program compares your signature to ones already on file from state records, like your driver’s license.

If there isn’t a match for the signature or the barcode, then the machine will kick your ballot into a reject tray. There are also some other reasons a ballot could be rejected, including a damaged envelope or one that’s returned without an envelope.

If your ballot does get rejected by the machine, a bipartisan team of election workers will examine it to determine why. But rejections are rare.

If the team doesn’t think the signature is a match, the county sets your ballot aside and contacts you through what’s known as a “cure process.” If you don’t respond, the county will not count your ballot. Instead they’ll send it to the local District Attorney’s office for potential fraud investigation. State records show fewer than .01 percent of ballots in elections are investigated for fraudulent signatures, though.

Once your ballot envelope is verified, either by the machine or through the cure process, election workers can finally open it.

The workers then pass your ballot along to the tabulation team. That’s where the vote counting begins.

Step 4: Ballot counting

After opening all of the ballots and placing them in stacks, they are then put in locked carts that workers roll to a secure room for scanning.

Here, a team unloads the stacks and feeds the ballots through a tabulation machine, which looks a little like a home printer. The tabulation machines use secure vote processing software and are never connected to the internet.

To count your votes, the tabulation machine takes a photo of your ballot. Then, the software reads which bubbles you’ve filled in and tallies them up with other votes.

If the machine can’t read your ballot for any reason, but your selections are otherwise clear (say you put a check mark instead of filling in the bubble like you’re supposed to), it’s passed off to another bipartisan team to go through a process called “duplication.” That means the team copies your votes to a clean ballot in order to feed it through the machine. If that happens, the county will invalidate your original ballot, but will keep it on file.

Once the ballots are counted, county officials upload their local results to the state’s centralized Election Night Reporting (ENR) system. To do this, they use a new or clean thumb drive to copy vote tallies from their offline voting system and transfer them to a protected computer.

At 7 p.m. on Election Day, the ENR software system begins to aggregate votes from around the state. Then it reports those results to the public.

Workers in county tabulation rooms aren’t able to see results while they’re loading ballots into the tabulation machines.

Once your ballot is scanned and counted, county workers prepare it for storage.

Step 5: Ballot audit

After the election, your ballot sits locked away for several weeks before it’s time to certify the results with an audit conducted by the Colorado Secretary of State’s office and county election workers.

In every Colorado county, bipartisan teams of election workers will pull random ballots and manually enter their votes into a software portal managed by the Secretary of State’s office. Its job is to compare the audited ballot’s physical entries to the scanned and counted ballot already on file from election night.

If those randomly sampled ballots match the count from election night, counties can assume with a high statistical probability that their tabulation machines accurately counted all of their votes.

Step 6: Ballot storage and disposal

Colorado law requires counties to keep ballots for 25 months after each election. That way, officials can have them on hand for recounts, public information requests or other needs.

Elections offices also keep digital files of each ballot on a secure server that is never connected to the internet. The files are part of the public record, so anyone could request them at any time after the election.