Hundreds of communities and states across the nation have filed suit against drug manufacturers and distributors in response to the opioid crisis. In Colorado, nine have already joined in the action and more than a dozen cities and counties say they’re considering the move.

Nationally, some reports show more than 450 communities and states have filed suit in federal court. Those cases have been consolidated in Ohio. The suits from Colorado could become part of that case.

The litigation is seen as a response akin to how states came together to take on Big Tobacco. The governments seek to be compensated for public spending borne out of the opioid epidemic; involving things like health care, social services, treatment, emergency response and an increase in crime.

Is momentum building for suits in Colorado?

Denver and 12 others governments, including Adams, Arapahoe, Jefferson, Teller and Boulder counties, and the city of Aurora said they’re considering whether to file suit. Also part of those collaborative efforts: the city and county of Broomfield, the cities of Black Hawk, Commerce City, Northglenn and Parker and the town of Hudson.

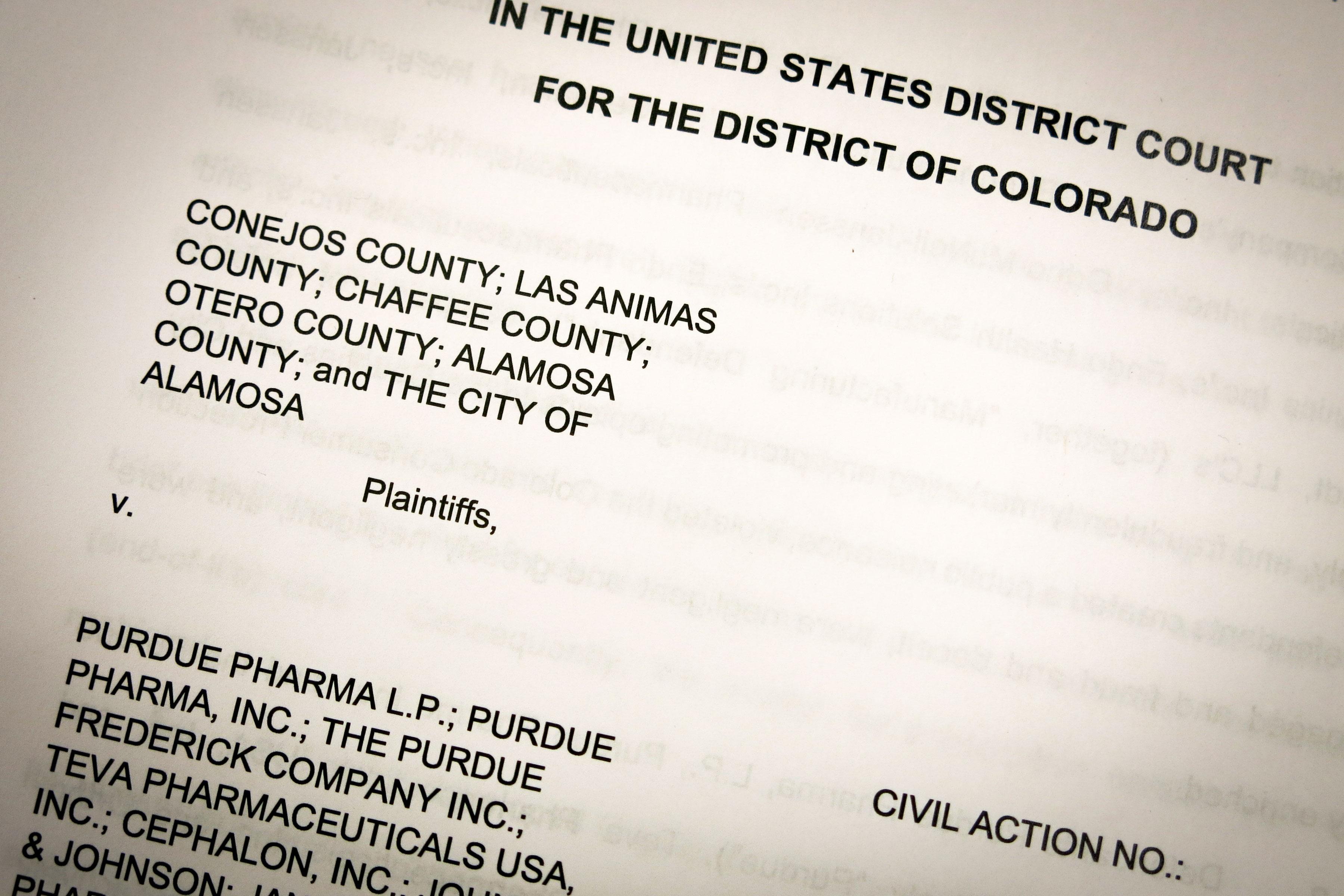

If those governments do sue, they’ll join six southern Colorado counties (Huerfano, Conejos, Las Animas, Chaffee, Otero and Alamosa) and the cities of Alamosa, Lakewood and Wheat Ridge.

Denver City Attorney Kristin Bronson said drug companies and distributors should bear some of the heavy public costs. “We believe that the industry has culpability and that the evidence will prove that,” Bronson said.

Where does the Colorado Attorney General’s office stand on this?

A bipartisan coalition of 41 Attorneys General is actively investigating the industry. A statement from AG Cynthia Coffman said she understands some cities and counties are “feeling the impulse” to sue. But said it’s her responsibility to conduct a “comprehensive and strategic investigation prior to filing any lawsuits.”

What specifically do these communities allege?

They allege that the companies used false, deceptive and unfair marketing practices and falsely claimed opioids aren’t addictive. The companies named in the suit by five southern Colorado counties and the city of Alamosa include Purdue Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, Cephalon Inc., Teva Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Endo Pharmaceuticals and Mallinckrodt LLC. Allegations against distributors include failing to monitor and report suspicious opioid prescription orders.

Otero County commissioner Keith Goodwin said communities like his have been flooded with opioid painkillers.

“I think what we’re having is there’s a lot of push by the industry on prescribing and it’s all profit motive,” Goodwin said. “That’s just my personal feeling.”

What is the pharmaceutical companies’ response to these allegations?

Drug manufacturers and distributors deny the allegations and say they will mount a vigorous defense.

The maker of Oxycontin, Purdue, did not respond to any requests for comment, but a statement on their website said the following:

“Inadequate treatment of pain and abuse of prescription pain medications are both serious public health problems that are increasingly at odds in our society. Corporations that make prescription pain medications have a responsibility to address both problems. For many years, Purdue Pharma has committed substantial resources to combat opioid abuse by partnering with healthcare professionals, patients, caregivers, communities, law enforcement, and government agencies.”

In 2007, Purdue Pharma and three executives plead guilty to federal criminal charges that they mislead regulators, doctors and patients about Oxycontin’s addiction risks and abuse potential. The corporation agreed to pay $600 million in fines and other payments, one of the largest figures ever paid by a drug manufacturer in a case involving opioids.

Another, Teva, said it works “to educate communities and healthcare providers on appropriate medicine use and prescribing.” It also said it is “developing non-opioid pain treatments.”

Johnson and Johnson, pointed out that labels for its medicines provide information about risks and benefits and the allegations are “baseless and unsubstantiated.”

What are we learning from the consolidated court proceedings in Ohio?

The drug companies have tried to have some claims dismissed.

Sommer Luther, a Denver attorney who specializes in personal injury and medical malpractice cases — she is not involved in the litigation, but is following it closely — said the companies argue you can’t prove a link between the drugs and the costs associated with addiction problems, because there can be other factors involved.

“The drugs may have been diverted, the drugs may have been found on the black market,” Luther said. “The drugs may have been prescribed by a physician in an inappropriate way.”

The government entities seem confident they’ll be able to prove a connection, based on internal company documents they’ll gain access to through the trial.

Is a settlement possible, maybe one in the multi-billion dollar range?

A possible large pot of money seems to driving a lot of the thinking.

Attorney Sommer Luther said the federal judge overseeing the consolidated case in Ohio seems motivated to encourage a global settlement that would provide resources to fix the opioid crisis. She said the Big Tobacco settlement with most states in the ‘90s provides a model.

“One of the huge criticisms of the Big Tobacco settlements is that the money never got to the municipalities or the local governments that really needed it,” Luther said — that’s one of the reasons cities and counties are getting involved in this case and could spur a bigger settlement than the roughly $250 billion figure in the tobacco case.

“The impact is so much broader that the end result I think is probably going to be something that could dwarf Tobacco,” Luther said.

Opioids however, unlike cigarettes at the time of the Big Tobacco case, are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Some defense attorneys say the suits by governments face a big hurdle because the agency approved the opioids as safe for treating chronic pain and warning labels of the products disclosed addiction risks.