For about three years, oil and gas drillers have suffered through low oil prices. In fact, they haven’t been this low for this long in more than a decade. Yet some of Colorado’s largest energy companies still seem optimistic.

Take Anadarko Petroleum. They pumped 33 million barrels of oil in Colorado in 2016, making them the state’s largest driller. The next closest competitor, Noble Energy, trailed them by 10 million barrels.

Why are they so active when prices are so low? One big reason: they own a lot of the mineral rights.

As Craig Walters, vice president of Rockies operations for Anadarko, explained at a recent Colorado energy conference, most companies go out and lease the minerals from whomever owns them and then drill. Anadarko’s advantage is they are the mineral rights owner, as Walters put it, “we actually get the full benefit, the full revenue stream.”

Anadarko’s unique situation goes back more than 150 years, to when the Union Pacific Railroad was granted the land and mineral rights around its rail lines in the West. In 2000, Anadarko acquired those minerals.

It turns out to have been a deal for the ages, because those rights cut through one of the most productive oil plays in the country: the Denver-Julesburg basin in Colorado.

“I mean the economics in the DJ basin are really, really good,” Walters later told CPR News. “And with Anadarko’s mineral interest ownership, that just gives us some enhanced economics, and so yes, we’re able to continue our program at low oil prices.”

Federal filings show Anadarko hasn’t turned a profit in years, losing more than $400 million last quarter. They’re a big enough company to withstand those shocks, and the quarterly losses have steadily shrunk in the last year. At the beginning of the oil downturn, the company lost $2 billion one quarter, and a $1 billion another.

Of course, it doesn’t help that the fatal explosion in Firestone led them to shut down wells and spend lots of money on inspections required by the state.

No matter what, low prices have forced all companies to become dramatically more efficient. Some research suggests oil only needs to be $34 a barrel now for drillers to breakeven in Colorado’s Niobrara formation.

Eric Jacobsen, senior vice president of operations with Extraction Oil and Gas, wouldn’t give a precise break even number for his company in Colorado. He did point out that it depends on where in the state they drill, estimating “in most cases it’s below $45 [a barrel].”

And that’s about the price oil’s been for the last couple of years.

Many efficiency gains have come from technological innovations. There may also be a dark side to extreme cost cutting. One class action case, filed earlier in 2017 against Anadarko, claimed the company failed to pay overtime wages for years. The company denies the allegations.

Bernadette Johnson, vice president of market intelligence at Drillinginfo, a Littleton-based energy analytics company, said the other big change in the industry is how agile U.S. companies have become.

“We can bring it on very quickly,” Johnson says. “So if you see a price bump, to $55 to $60, for whatever reason, a geopolitical event, whatever, our producers respond very quickly. They lock in hedges, they start drilling. You can bring those wells on within a couple of months. It’s very different production here than it is anywhere else in the world where you have to have years lead time to get those things online.”

Few believe crude oil prices will get back to $100 a barrel, like in 2014. So energy-producing states like Colorado, and local governments near the activity, like Weld County, need to get used to lower tax revenue from drillers.

“That’s going to take a hit, and it already has, and it’s permanent,” Johnson says. “So should we be banking on the same type of royalty payments, the same type of tax revenue we saw at $100 a barrel? No. And that doesn’t come back.”

Still, signs of life in the industry are welcome news. Permits for future drilling are up slightly in Colorado, 1,565 this in the first half of 2017, a 24 percent increase.

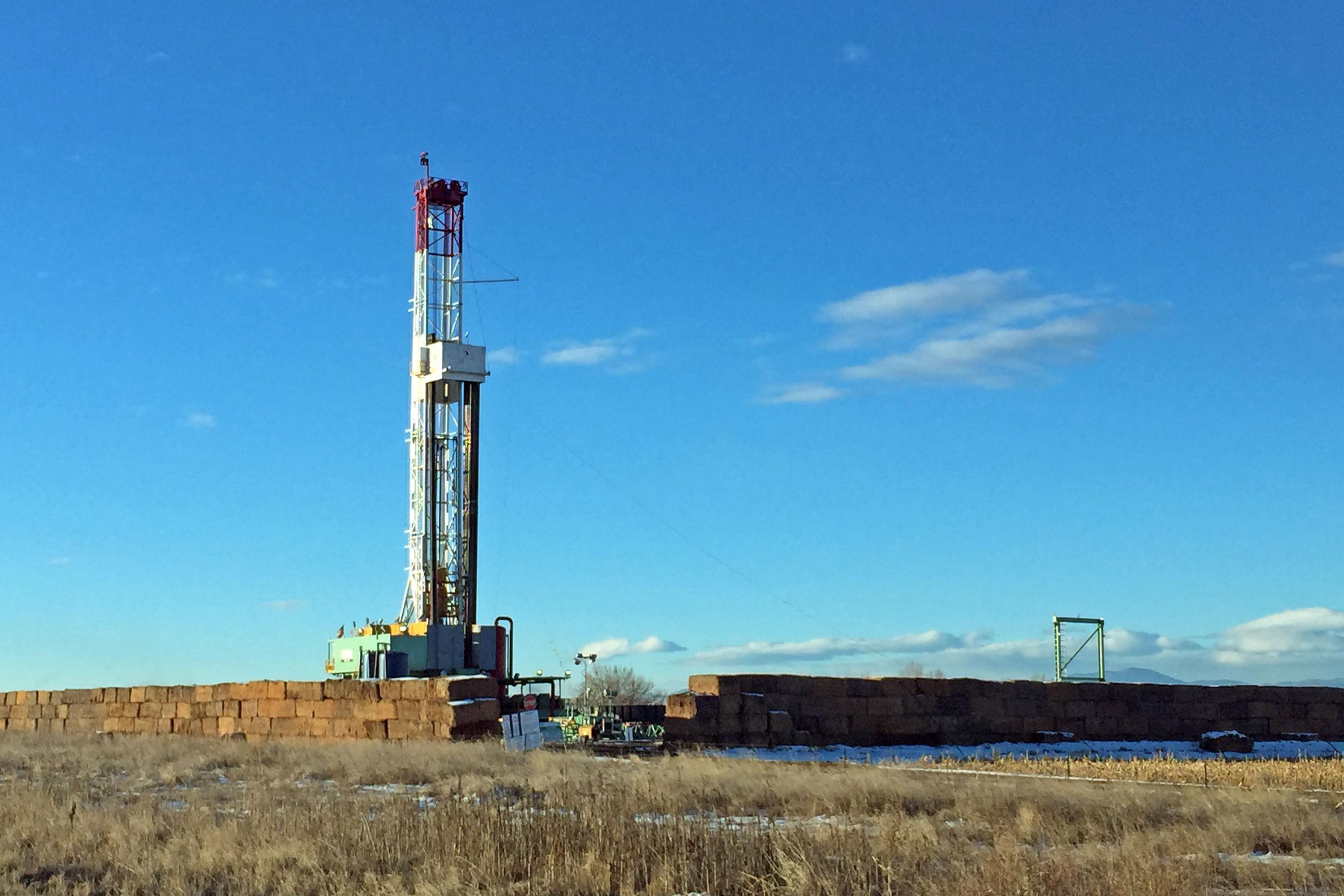

Everything is relative though. To be clear, this isn’t a prelude to a drilling bonanza. There are only 37 total drill rigs operating statewide, according to Baker Hughes. That’s half the number from three years ago. Yet, a dozen or more drill rigs have come online in the last year, and there are signs that hiring is picking up too.