This story is part of the NPR reporting project "School Money," a nationwide collaboration between NPR’s Ed Team and 20 member station reporters exploring how states pay for their public schools and why many are failing to meet the needs of their most vulnerable students.

Colorado’s economy is hot. The unemployment rate is 3 percent. And shiny new skyscrapers are rising all over Denver as revelers pour fistfuls of cash into downtown bars and restaurants.

But no one invited Colorado’s public schools to the party.

"They have outdated technology, larger class sizes. They've lost the opportunity to offer certain programs. They can't retain teachers. They can’t attract teachers," says Tracie Rainey with the Colorado School Finance Project, a nonprofit research group. "They've had fewer school days, furlough days, all sorts of maintenance issues."

The list goes on. Many educators and parents had hoped that, as Colorado’s economy roared back from the Great Recession, the nearly $5 billion that lawmakers had cut from the state’s public schools would come back with it.

They were wrong.

"I was told that an improved economy would mean cuts would continue," says Shannon Bird. The concerned mother of two school-age children lives north of Denver and has made several trips to the state Capitol to lobby for more funding. "Lawmakers told me their hands are tied."

How is it that the nation’s 14th richest state ranks 42nd in how much it spends per student? Especially in a year that taxpayers can expect rebate checks from the state totaling $156 million?

Most Restrictive In The Country

The simple answer is, that’s what voters wanted. In 1992, they amended the state’s constitution with something called the Taxpayer’s Bill of Rights, or TABOR.

To many Coloradans, TABOR sounded like a good idea. It required that voters, not lawmakers, have the final say on tax increases, and it capped tax revenue. Anything the state raised over that cap -- typically in boom years -- would be refunded to taxpayers.

Republican Sen. Jerry Sonnenberg, R-Sterling, says TABOR was about trust.

"The people of the state of Colorado, I’m convinced, especially in my district, until the government figures out how to manage its own pocketbook, don’t want to give them any more money out of their own pocketbook," Sonnenberg says.

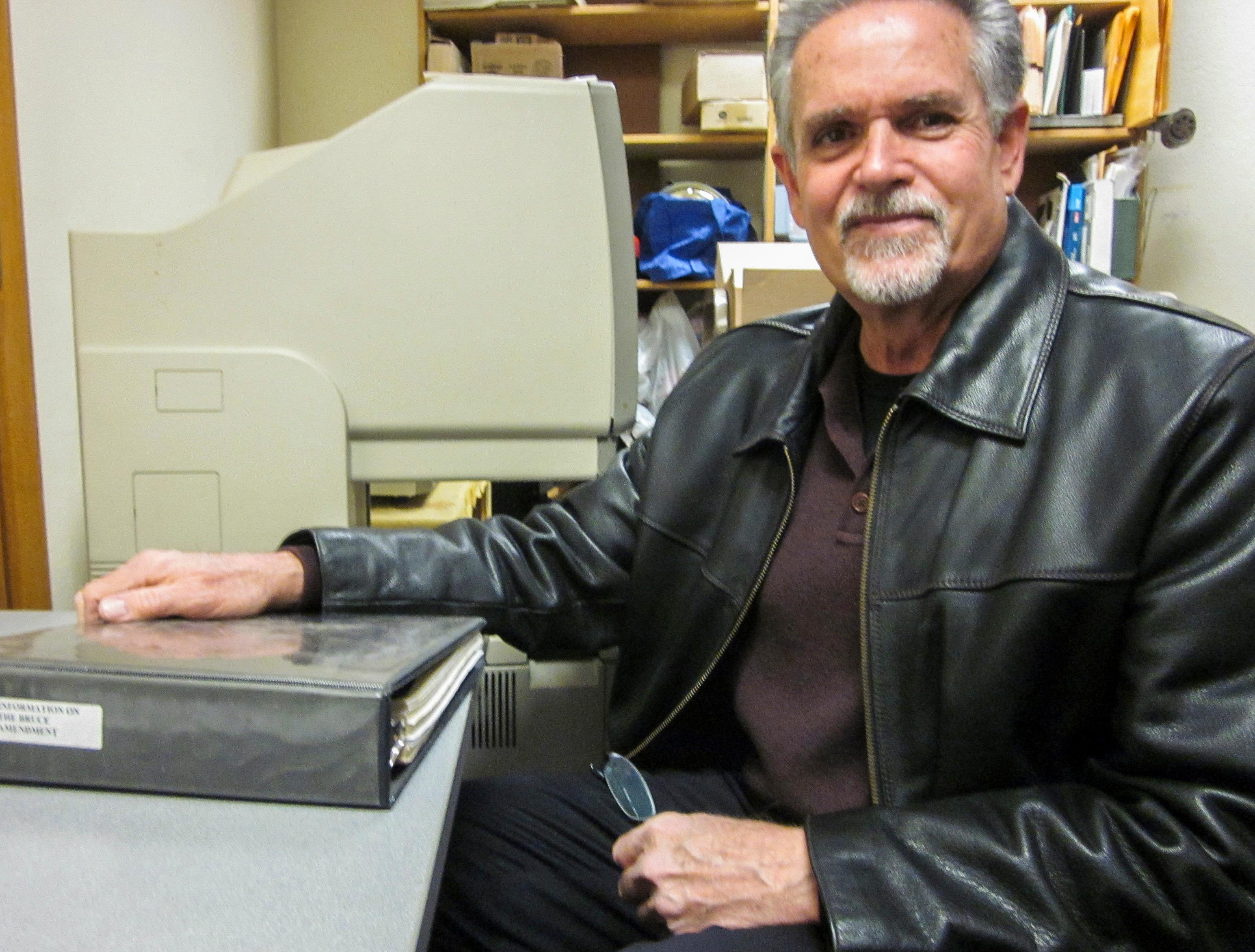

Even back in ‘92, before TABOR had become law, at least one man worried about its potential impact on schools.

"Colorado is viewed nationally as having the most restrictive tax and expenditure limits in the country," says Charlie Brown, who was then legislative council director. Here’s why Brown was worried:

Those caps aren’t likely to change, either. Once voters put things into the constitution "they're frozen virtually perpetually in time," says James Griesemer, who directs the University of Denver’s Strategic Issues program. "The legislature can't change them. And so the legislature's field of action in Colorado has been progressively narrowed."

Constitutional Stew

"I don’t think people on average knew what it meant, especially long-term," says Rainey, with the Colorado School Finance Project.

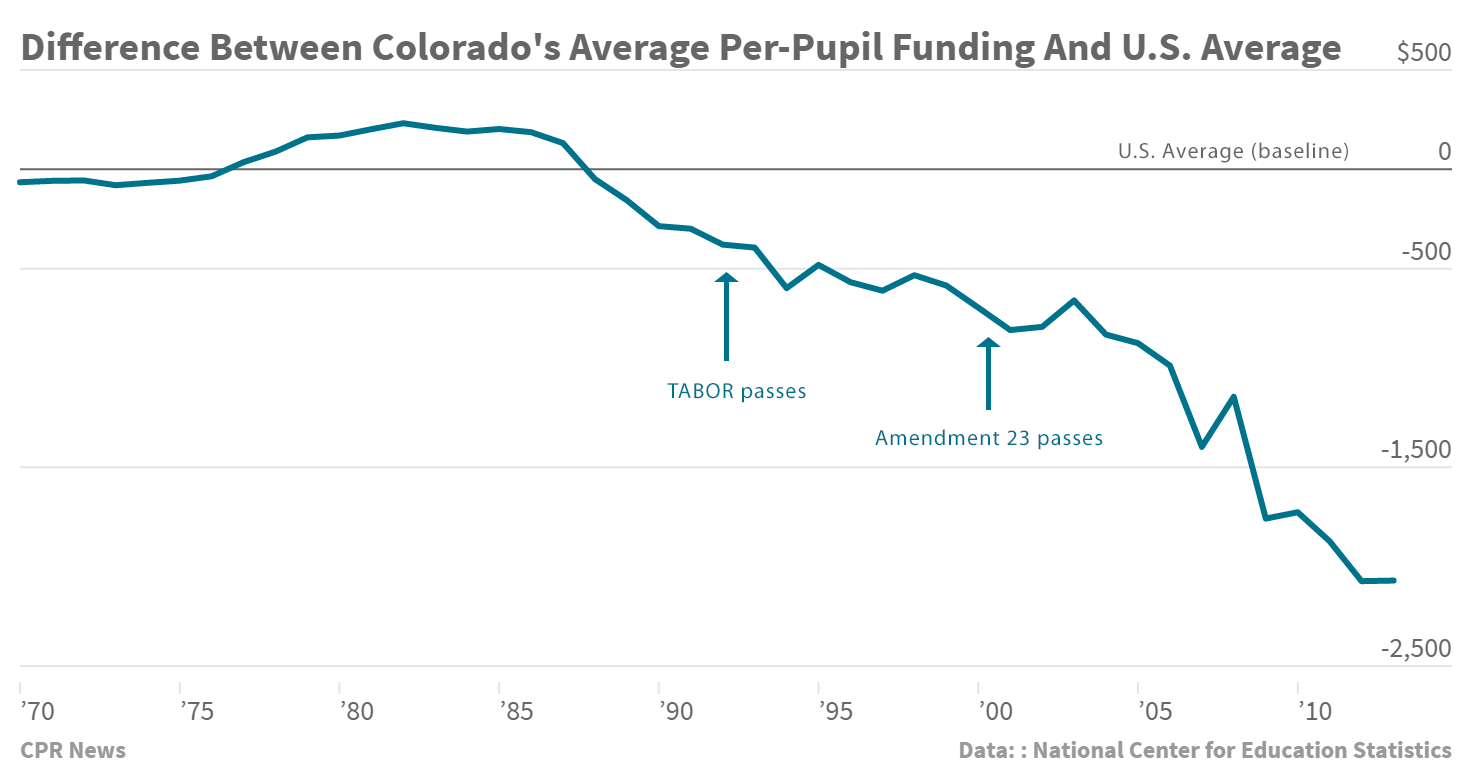

She says TABOR forced schools to make deep budget cuts. When voters began to notice, several years later, they passed Amendment 23 to increase school spending. But, with TABOR still on the books, the two measures worked against each other.

"In effect, we had TABOR putting its foot on the brake of government spending and Amendment 23 putting its foot on the accelerator of government spending. And of course you had a conflict," says Griesemer. "What you have is a constitutional stew of disconnected ideas."

Then came the Great Recession, and the brake won.

Lawmakers didn’t have the money to implement Amendment 23. Instead, they reinterpreted it in a way that let them cut about $1 billion a year from public schools. That shortfall is now nearly $5 billion.

As a result, according to Education Week, Colorado spent roughly $2,500 less per student in 2013 than the national average. That ranks Colorado below two of the poorest states in the nation: Mississippi and Alabama.

"So the state now is balancing their budget on the backs of students," says Rainey.

Jon Caldara sees it differently. He’s president of the Independence Institute, a Colorado-based free market think tank, and says TABOR’s a big reason the state’s economy is doing so well. As for its effect on schools, Caldara says, more money isn’t the answer.

"I think parents and family members and taxpayers are saying, ‘No. Fix the problems. Use the money you have more wisely and educate our children,’ " he says.

Several recent attempts to approve more money for public schools have failed. Still, that hasn’t stopped advocates from announcing their latest ballot drive. They want voters to forego their refund checks and let the state keep those surplus tax revenues.

This year, thanks to TABOR, Coloradans are on track to get $156 million back -- or roughly $19 per person.