There's only three known specimens of the Rhinconichthys -- and one of them was discovered in Colorado.

This ancient fish was about 8 feet long, with a huge jaw and no teeth. It strained its food from the water like some whales. Now it's part if the collection at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

Paleontologist Bruce Schumacher says the find is exceptionally rare. He and a colleague discovered the fossil on the Comanche National Grassland in southeast Colorado.

"This fish was not known in the western hemisphere, anywhere, so this is the only specimen in the western hemisphere in the New World," Schumacher said. "And if you go to the Old World the only two specimens previously known are from the United Kingdom and Japan. So this is one of three representatives of an entire family of organisms known anywhere in the world."

Why were these three fossils found so far apart?

"That is a little bit of a curiosity yet. But I think part of the answer is that there may be unrecognized specimens of it in collections in museums in the form of a fin but it is hard to ascribe that fin to a animal whose skull we don’t know about or whose body we don’t know about.

"The second thing ecologically is these may have been a very rare component of that ecosystem. Maybe there weren’t a lot of these fish in the ocean or maybe they inhabited areas of the ocean that we just haven’t explored very well."

This fish is something like 92 million years old. What was Colorado’s environment like then?

"So what we think of as the Great Plains as the remnant of a great ocean. The interior of north America was flooded from the Gulf of Mexico up to Hudson’s Bay and these layers where this fish was found in are right at these highest water levels of that ancient ocean."

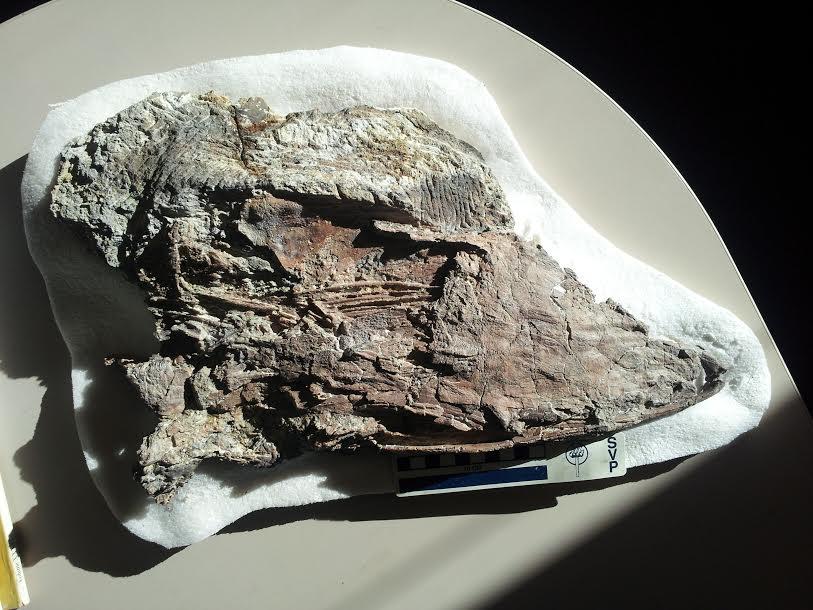

If you look at this fossil would you know it was an ancient fish?

"It would be a little difficult to be honest with you. The skull is crushed because it was buried thousands of feet by overlying rocks - rocks that have since been eroded away. So it’s very compressed, flat, very crushed. And it’s not crushed in a neat way.

"It’s sort of smushed. That’s the term I would use. So to a scientist, it’s a marvel. It’s a beauty to look at. But to a casual observer they would scratch their head and ask, 'what is that?'"

In your 20 years as a paleontologist is this your most unusual find?

"Yes and no. I’ve found things I personally am more excited about. I specialize in reptiles. I’ve done some work with dinosaurs. We’ve found some rather fantastic things, but no, I haven’t even come close to finding an example of a fossil that is the only one in the Western Hemisphere. No, I’ve never come close to that. I don’t think I will ever again. This is probably the most important fossil I’ll ever find in my life. I hope not but it seems like it would be hard to surpass it."