Coloradans will vote on a matter of life and death this election. Proposition 106 on the ballot, the "Colorado End-of-Life Options Act," would allow people who are terminally ill to get a prescription and end their own lives.

Our Colorado Matters debate features Julie Selsberg, a Denver attorney who supports the measure, and Carrie Ann Lucas, an attorney and disability rights activist from Windsor.

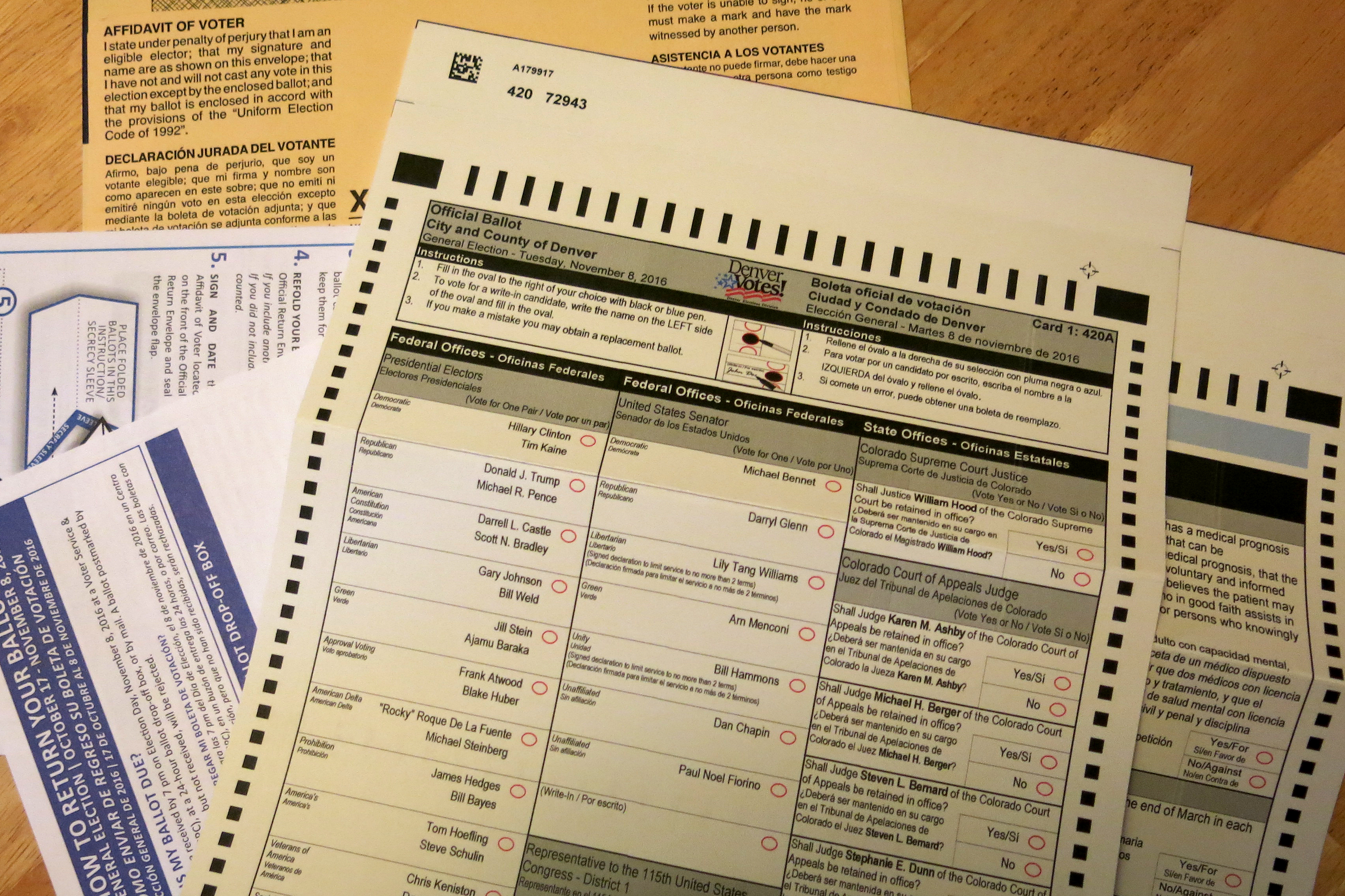

Proposition 106 Ballot Title:

A change to the Colorado revised statutes to permit any mentally capable adult Colorado resident who has a medical prognosis of death by terminal illness within six months to receive a prescription from a willing licensed physician for medication that can be self-administered to bring about death; and in connection therewith, requiring two licensed physicians to confirm the medical prognosis, that the terminally-ill patient has received information about other care and treatment options, and that the patient is making a voluntary and informed decision in requesting the medication; requiring evaluation by a licensed mental health professional if either physician believes the patient may not be mentally capable; granting immunity from civil and criminal liability and professional discipline to any person who in good faith assists in providing access to or is present when a patient self-administers the medication; and establishing criminal penalties for persons who knowingly violate statutes relating to the request for the medication.

Full transcript:

Ryan Warner: This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. I’m Ryan Warner. Coloradans will vote on a matter of life and death this election, Proposition 106 would allow people who are terminally ill to get a prescription and end their own lives. Today an explanation of how this would work followed by a debate with an opponent. Here with me now is Denver Attorney Julie Selsberg who supports the measure. She wishes her late father had had the option. He suffered from ALS and to hasten his death, he stopped eating and drinking which she says was an excruciating 13 day process. RW: Julie, welcome to the program. Julie Selsberg: Thank you, thank you for having me. RW: Walk us through this briefly. How sick does someone have to be to qualify under this proposition? JS: Somebody has to be terminally ill as determined by two different doctors and they have to have been determined to have a prognosis of six months or less to live. RW: By two different doctors? JS: That’s right. RW: Explain that. JS: Well, the measure provides that you have an attending physician and that attending physician goes through a very thorough examination, among other things to determine that you are mentally capable to be having these discussions; that you have been given all the options for palliative care, pain management, treatment, everything like that; and, that you have demonstrated that you would be making an informed decision. But then that has to be confirmed by a consulting physician who’s also defined in our measure. And both the attending physician and the consulting physician are not just any doctor. They are doctors who are familiar with the patient, familiar with their terminal illness and familiar with the treatment for that terminal illness. RW: Is it just the doctors or who makes sure that this is indeed the patient’s independent decision, there’s nobody coercing the patient for financial or other reasons? JS: Well, part of the provision is that when the doctor is in effect screening or meeting and making sure that this patient can qualify to receive medical aid in dying, they meet with that patient alone. So they are – there’s nobody else in the room, there’s no family member, no caregiver, nobody else and they make the determination like they do when they meet with a patient on any serious medical issue, that this person has the mental capacity and that they are not under any coercion or undue influence to be requesting medical aid in dying. RW: I believe the proposition does call for two additional witnesses or signatures of some kind. Tell me about those figures. JS: Right. So there are a number of safeguards that are built in to this measure and I want to point out that this is not just something that we have whimsically put together. This is a comprehensive set of statutes. This is a package that has been tried and tested in other states namely, Oregon, where it has been in effect for more than 18 years. And so the safeguards that are built in include not only that two doctors confirm the terminal diagnosis but that the patient has to see their attending physician, not once to request the medication, but twice and that has to have a separation in between of at least 15 days. A third request comes in the form of a written document and there is an example of the written form in the actual statutes in the measure and, again, this is a statutory addition to our laws. RW: Rather than Constitution— JS: Constitutional amendment. So the actual form has to be witnesses by two individuals and those two people, one of them cannot be related to the patient who is signing; one of them cannot be that attending physician; one cannot be anybody who is working in a healthcare facility where that person might reside; and, they can’t have durable power of attorney or medical power of attorney. RW: What is the drug? JS: It is a barbiturate. It’s a strong dose. It would be mixed together. You’d take them out of the capsules and you mix it together and you could administer it, I think, most people do it by drinking it or some might mix it up into like an applesauce or a pudding and it’s combined with another like an anti-nausea drug so that the bitterness of the medication doesn’t make somebody vomit. RW: The proposal says the patient has to self-administer the drug. JS: That is the most important part. RW: How would that have worked in your father’s case, for instance, because he lost a lot of motor skills? JS: He did but the way the ALS presented itself and progressed in my dad was sort of the respiratory and the upper, from the chest above, those symptoms first. So when my dad decided to stop eating and drinking, he still had some mobility left in his hands, his arms. He could have picked up a drink and sipped from it and my understanding is the other ALS patients who have taken this, have taken advantage of medical aid in dying do the same thing. They don’t wait until their body is in total lockdown in order to self-administer. RW: Would there be cases, though, where someone simply lacked the motor skills to do so? JS: Yes, there would and then unfortunately, they do not qualify. RW: They do not qualify. JS: They do not qualify. This is absolutely self-administer. RW: Very briefly what rights does a doctor to have who does not wish to take part in this system? JS: The nice think about our measure that is not included elsewhere in other states, we have built into our statute a provision that says if you do not wish to participate in this you do not have to. Nobody has to participate in this, not a patient, not a doctor. The only thing that the doctor has to do is then provide the medical records if the patient chooses to seek a second doctor for help. RW: Julie Selsberg, thanks, we’re going to take a break and then speak to an opponent of this measure. It’s Prop 106, also dubbed the Colorado End of Life Options Act and then later a chance for the two of you to engage with each other. ... Today we’re discussing Proposition 106 on the November ballot, that’s the Colorado End of Life Options Act. It gives terminally ill patients the ability to request medication to end their lives. Before the break we spoke to a supporter, now an opponent, Carrie Ann Lucas, is a lawyer and disability rights activist and Carrie Ann, welcome to the program. Carrie Ann Lucas: Hello, how are you today? Thank you for having me. RW: Pleasure to have you on the program. What’s the biggest risk you see in this proposed law? CL: I think the biggest risk is the lack of safeguards in this so while Miss Selsberg talked about a number of things the law says, there are also a number of things I think it exaggerates some of the points because those things are simply not required and put people at risk, particularly the most vulnerable people in our population. RW: Can you give me an example of the safeguard or two you wish you could see in this? CL: Well, I think when you first talk about the notion that this is for terminally ill people, this is for people who are within six months of death without any other treatment. So that does not mean this is intended only for people who are dying. This is for people who have any sort of chronic health condition that without treatment could result in death, including everybody in the state who has type one diabetes is eligible for this law. So it’s extremely overbroad in its definition of terminal enough that’s a significant concern. RW: How is it that anyone with diabetes would be six months away from death. I don’t understand that? CL: Because it’s six months – it’s if you’re within six months of death without treatment so if you take away insulin, everybody with type one diabetes is within six months of death. RW: So you’re saying that people with diabetes are terminally ill as defined by this? CL: Yes, how terribly broad this measure is and that’s the concern is that the measure is simply too broad and not safe for Colorado. RW: Do you want to site another example of a safeguard you’d like to see? CL: One of the other concerns is the discussion of, first of all, physicians make mistakes, physicians aren’t infallible. In 2014 there was a report that 12 million Americans each year are at risk of misdiagnosis and half of those risk serious harm. So this Proposition 106 will make the harm lethal so if you receive your prescribed overdose from your doctor and their colleague after they totally misdiagnose you and then you die, no one will ever know. There’s no chance to fix that. So there’s the other problem it’s oftentimes doctors will say somebody’s within six months of dying, but they really, really are not and we know that from the statistics in Oregon where people have lived for years after receiving their lethal prescription and I know Miss Selsberg's response is, oh, well, of course if somebody lives that’s great. But where with this measure allows people to see suicide assistance who are nowhere near death. If it’s intent is only for people who are near death and the measure should say that but instead it’s overly broad such as including people who have any sort of medical condition that could result in death without any sort of treatment. The other problem is that there is the rates of elder abuse. One in 10 elders are abused in Colorado at the hands of their family or caregivers. So while Miss Selsberg and her family very much loved her father and he was fortunate to have such a loving family around him, that’s not the case for a substantial portion of the population in Colorado and those are the people most at risk so, while yes, you could – the person does have to make this request themselves but that doesn’t mean that they don’t have a family member encouraging them and pushing them to go make a request for the prescription. They could, that family member who is set to inherit, which is, as an attorney, I can't have somebody who is set to inherit witness a will. But under this measure, I could be, a person could be set to inherit from a person and sign their death request. They could then, that person, not the individual who's getting the lethal prescription, the family member could then go fill the prescription, bring it home and administer it to the person, since there's no witness required at the time of death. Nobody would know. RW: I just want to say the language of the measure does say 'terminal illness means an incurable and irreversible illness that within reasonable medical judgment would result in death'. And I want to underscore the fact that one of the signatories, the sort of testifiers, cannot have a financial interest with the patient. Just to read from the measure. RW: Yes. Let's take a break and then I'd like to bring you both on, you've made reference to Miss Selsberg, that's Julie Selsberg who we heard before the break. ... Julie Selsberg, you've heard Carrie Ann Lucas' concern that this law could be used to coerce people and that there is some potential vagueness in the six-months-to-live diagnosis. A doctor can be wrong about that. How do you respond? JS: So the first part about that there could be coercion, first of all, you have to know that this has been in place in Oregon since 1998. And you have to put in perspective, 4 million people live in the state of Oregon. In 2015, 218 people requested the prescription and 132 actually took it. This is not a huge group of people who qualify and are looking for this option. RW: Hasn't Oregon lost track of what some of the requestors have done with the medication? Their results? JS: There is some unreported results yes but the idea is that it gets caught up by the next reporting cycle. RW: Oh right. And to the second point that a doctor can be wrong about a six-month-to-live diagnosis. JS: That's right and it can happen and so I think that's fabulous if a doctor is wrong. Nobody is telling the patient and in fact the doctor counsels the patient, you don't ever have to take this medication. And only the patient can know when their suffering has become too great and that it has become too much to live with that kind of suffering. And only they can make that determination of when it becomes too great. But you have to also know that just having this medication in hand, 36 percent of the people over time in Oregon who had had that medication, never took it. That speaks volumes about the peace of mind it brings to somebody who is terminally ill and fearing a horrible death. They never take it, in 36 percent of the cases. RW: I want to put one finer point on this; the doctor, the primary physician, is not present at the taking of the medication, correct? JS: The doctor absolutely can be present if that is the patient's choice. But again we are talking about people who are in their last stages of dying. We have front-loaded all of the requirements so that the doctor knows that the person is making an informed decision, that they're mentally capable and that they are safe. So it is up to that person to decide if they want just their family around, if they want to include a health care provider or not. RW: Carrie Ann Lucas, your response? CL: Well looking at this issue of whether or not, whether somebody should be present at the time of death, we know from the statistics in Oregon that sometimes the meds don't work as prescribed. Sometimes people wake up, sometimes people vomit, sometimes they make people violently ill, so it's important to have a medical professional there in case something goes wrong. But most importantly, it's important to have a witness there. An unbiased witness at that time when these drugs are administered to ensure they're being administered as they're supposed to and it's a simple protection that's not in the law because it's not, we're not worried about the people who have good families around them. We're worried about that 10 percent of Coloradans who have abusive family members. Those are the people who are most at risk because this law, this proposed law does not create really rights but rather creates new immunities for perpetrators. RW: Julie, how do you respond? JS: I would say the Oregon statistics show that the majority of the people, more than the majority, 90 percent-something, are using the end of life medication in hospice care. So in reality, their families are around, or somebody is around. But again I go back to the reality. Both my parents died from terminal illnesses and as their point of dying became closer, they really narrowed down who was around them, in their circle, and it was immediate family. And their moment of death is of such monumental intensity, it is not a place for someone who does not belong. It is for the immediate family. RW: And so that is your argument for why you don't mandate that a doctor be there. Is that right? JS: Well, plus what I said before, which is that the person has already been screened, they have already proven their capability. RW: So Carrie Ann, I want to make room for a point, a concern that you have which is as someone with a disability and who's connected quite intimately with those who have disabilities, as a disability rights advocate, you fear something of a slippery-slope here. Can you just explain that a little bit? CL: We really believe that this law is, first of all, not necessary. People, people can get adequate pain relief. People can access things like terminal sedation in order to relieve their pain at the end of life and this really puts too many people at risk for the very small, small number of people who would benefit because we are concerned with the greater good. What we have collectively, disabled people have a lot of experience with the healthcare system. We're kind of like the canaries in the mine so to speak, when looking at the healthcare system. And because we're experienced, we know how our lives are devalued by the medical system. We also know how the profit-driven healthcare system and cost-containment medical care system really values the bottom line over proper care. So we're very much concerned that people will be, will have that type of coercion, such as what happened to Barbara Wagner and Randy Stroup in Oregon who were individuals who had advanced cancer, wanted additional chemotherapy to relieve some of their pain and some of the, and they weren't seeking cures for their cancer, but rather treatments that would extend their quality of life that were denied by the Oregon health plan, which is Medicaid in Oregon and instead were offered a lethal prescription as a so-called treatment option. That's our concern is things like that can continue to occur and really coerce and provide that sort of financial coercion and that not, you must take this medication or I'm going to beat you type of coercion, but rather that more silent, that more insidious type of coercion that causes people to act. And that's the concern. Because we have a healthcare system that's fatally flawed. It is so so poor for so many people and this measure does not promote that. RW: Julie, what do you say to the case in Oregon that Carrie Ann references? JS: Well I have several things to say. Number one, the Barbara Wagner case, it's a drawn out case and she's misrepresenting what happened. Barbara Wagner had asked for experimental treatment and this is not unique to Oregon insurance or the Oregon state-provided insurance, most insurance companies, if not all, have a provision about experimental treatment. And so that's what happened to Barbara Wagner. But I want to step back to two other things that she said. Number one is that people can get adequate pain relief and they can have palliative sedation and that is just not true. I know it for myself, I know it from speaking to hundreds of people across the state and we have five hundred volunteers who went to collect signatures and nearly every one of them has a story of a loved one who had suffered a painful death and that palliative care and pain management did not work. I am not saying this is a replacement for any of those things but there are a certain small percentage of people for those things do not work and this is just one more option. RW: And to your second point, just briefly. JS: I would also like to point out that the Disability Rights Oregon, which is the group that is tasked with investigating cases of abuse, coercion or neglect to disabled individuals in Oregon, they have stated they have not received a complaint of abuse or exploitation from people with disabilities in Oregon since the Death with Dignity Law has become legal. RW: You say that palliative care is not perfect, but why not spend the energy there as opposed to focusing on this measure? JS: In Oregon it has shown that palliative care and these discussions around end of life options has improved since end of life dying became legal there. That's great. Let's put more effort into end of life care in Colorado. This is not replacing it. RW: All right. More of our debate about Colorado's medically assisted death proposal after a break. ... Voters in the state will decide whether terminally ill people should be allowed to end their own lives. We are debating proposition 106 on the November ballot with support Julie Selsberg and an opponent, Disability Rights Advocate Carrie Ann Lucas. Supporters of this initiative have raised $4.7 million, opponents have raised about $1.25 million. One argument that's made on this issue often is a religious one. Denver's Catholic Archdiocese and the Colorado Springs Evangelical group Focus on the Family both oppose this idea. The archdiocese has contributed $1.1 million to the fight against it. In a recent blog on the Archdiocese website, Denver Archbishop Samuel Aquila wrote, "The most important shortcoming of Prop 106 is that it treats human life as something that can be discarded—Like an appliance that has outlived its use. Human beings are vastly more valuable than that and our dignity does not depend on our ability to perform functions, or on our health." He continues, "Our dignity comes from the fact that a loving God made us in his image and likeness and gave us souls that are eternal. The state does not bestow dignity on a human person. God does." Julie, can I get your response to that? JS: I can't argue with somebody's religious beliefs. If that is their belief and they believe in suffering at the end of life, that's not my place to say anything. What I would say is please respect other people's opinions who want this option and who don't share the same beliefs. RW: Have you had conversations with deeply religious people about this since you've campaigned? JS: There are plenty of people of faith, of strong faith, who support this. And we have a website where we keep track and people can contribute their stories and there are plenty of examples of people who maintain their faith but don’t believe in suffering at the end of a terminal illness. RW: Carrie Ann Lucas, I'd like to let you weigh in on this faith question. CL: Well we really [come] from a social-justice rather than a faith perspective. Those of us in the disability community and while, again, I'm not going to discount anyone's faith perspective on this. We really look at it as we need to ensure that our laws protect those who are the most vulnerable in our population which is how laws are generally written is to protect those, such as child abuse laws and so forth. And this law does not do that, in fact it really creates a lot more risks for people who are already being abused and neglected and it just places those people at further risk and that's our biggest concern. RW: Carrie Ann, is there something in your own experience as someone with a disability that leads you to believe those with disabilities are especially vulnerable? You've talked about what you see as inherent flaws in the healthcare system that somehow get amplified by this. Help me understand your experience. CL: Well as an individual with a severe disability myself, I'm a quadriplegic, I have, I use a ventilator full time, I have seen how my life has been devalued by the medical system. I've been discouraged from seeking medical treatments before in the past, medical treatments that have extended my life by more than a decade. I've also seen my children, who also have disabilities, I've also seen their lives be devalued. But I think the biggest concern is is what happens if I were to become depressed. Just like any other middle aged woman, I could experience depression. And I would hope that my doctor would send me for treatment and not offer me a lethal prescription if I asked because my doctor knows me well. But nothing in this measure would prevent me from doctor shopping. So while there was a discussion earlier, oh the doctor has to know you, there's nothing in this measure that says that. It just says it has to be an attending physician. An attending physician is someone who's seen you once. So I could switch to another doctor, until I found another doctor who would give me a lethal prescription rather than at that moment the suicide prevention I would so desperately need, I would get suicide assistance. And that's because we know the medical establishment has a very negative view of disability and living a life with a disability. So if I went to a doctor and said oh, I'm tired of living with the disability and I could identify all of the things that doctors, the biases they have against people who live lives like mine, I would walk away with a lethal prescription. I could even have my kids sign one, somebody in the doctor's office could be the other witness. RW: Let me have Julie respond to this question of doctor shopping. So this is obviously something we saw after medical marijuana was passed in Colorado, that it was really a concentrated number of physicians that were handing out recommendation cards. Could something similar happen with this? JS: Well, there's so many things to answer with that. Yes, you could seek another doctor if your doctor does not believe in that practice. But what we have in Colorado, we have the Denver Medical Society who supports this proposition. Boulder Medical Society supports this proposition. Pueblo Medical Society supports it and just two weeks ago, the Colorado Medical Society moved from a position of opposition to a position of neutrality because 56 percent of their doctors support this and decided that it is up to the patients to make this decision for themselves. RW: But neutrality is by no means a ringing endorsement from that group of doctors. JS: Well 56 percent of this group do support it. So as a group, they weren't ready to move to actual support but 56 percent of their doctors do. And so I go back to the provisions of the statute and the safeguards. Attending physician is a physician who has primary responsibility for the care of a terminally individual and the treatment of the individual's terminal illness. RW: I want to thank you both for spending such a nice chunk of time with us. We heard from Julie Selsberg, a Denver Lawyer who supports Prop 106. You will see it on your ballot as the Colorado End of Life Options Act. And Carrie Ann Lucas also joined us, lawyer and Disability Rights Activist from Windsor, Colorado. I'm Ryan Warner. This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. Thanks for being with us. |

Related: