Teachers in Denver Public Schools, the state’s largest district, have tried their best to help students process a new president some weren’t expecting.

Three-quarters of Denver students are minorities, some undocumented, some Muslim. President-elect Donald Trump has promised mass deportations of undocumented immigrants and a ban on Muslims from entering the U.S.

As the final election results came in, Denver teacher Rebecca Del Toro knew she needed to do something -- and she was ready. That’s because about five years ago, Del Toro felt she needed to prepare to help her students process traumatic events. The special education teacher at Collegiate Prep Academy said social media means more information gets out about school shootings, police shootings, and sometimes, hate speech.

“Whenever something happens that can re-traumatize that community, I need to be prepared,” she said. “I need to respond. I need to address it. The plans go out the window, the plans go out the window and I need to address this.”

After the election, Denver Public Schools deployed teams to various schools. Some held hour long assemblies to let students process their emotions. Allen Smith, DPS’s associate chief for culture, equity and leadership teams, said the district will explain to undocumented families that students will still be educated under federal law. They’ll also be providing training for teachers on empathy.

“Because students are going to be carrying this emotion,” he said. “But I don’t want people to panic and I don’t want people to act off of emotions, so it’s important to give our teachers training in how to help our students and even our families not make rash decisions off of emotion.”

He said teachers can also play a role helping students distinguish between rumors and reality. The district said it will closely monitor attendance and dropout rates going forward, which can spike particularly among undocumented students who may feel a sense of hopelessness about their futures.

Emotional Students

The weeks before Trump takes office will be nervous ones for some teachers. Some have already dealt with high school students breaking down in class.

In the Boulder Valley School District, where minorities make up just 20 percent of students, officials hoped a memo to guide teachers on post-election discussions would help. But Boulder High freshman Alejandra Floripe said none of her teachers talked about the election.

“Our teachers avoided the problem,” she said, tearing up. “They acted like nothing happened. No one was there to talk to us or just help us out because it’s hard for us minorities.”

She and her friends wanted to talk about their fears. Floripe has extended family members who are undocumented.

“Our loved ones are going to be gone if they don’t have documents, if they don’t have papers, our families are being taken away,” she said.

In Denver, the first students who walked into Rebecca Del Toro’s Collegiate Prep Academy were clearly distraught. Del Toro said they sought out teachers and a place where they could talk.

She tried to address their fears with a circle exercise she developed for when she knows her students are particularly upset about an event. First, they started with a meditation to build respect. Then each student said one word about how they felt.

Then the questions poured in: What powers does a President have on his own? Which need to get Congressional approval?

“Of course they asked me, ‘Can he just deport people? Can he just put a ban on Muslims entering the country?’ One of my students asked about abortion access. A lot of the questions were, ‘Is it true, is it true that he can just sign away our rights as that we have worked for throughout history? Can he just sign a paper and it will be gone?’”

A Teacher’s Open Letter

The academy’s civics teacher, Richard Elkind, was already thinking about this in the hours after the election. Since his students had spent time researching polls, data, analysis, and had made their own predictions, he wanted to address how and why the polls were wrong.

He also would share a letter he wrote to them at 2 a.m.

In the letter, he acknowledged that the election makes him worry about America’s relationship with the rest of the world and the Supreme Court nominees. He also told them that as America has globalized, many Americans have been left behind and the frustration Trump speaks to is real.

Elkind is scrupulous about not sharing his political beliefs with his students – he wants them to think for themselves, to make up their own minds – but in his letter, he shared that he was nervous and scared.

“I have to also acknowledge these are the same emotions that animated many Trump voters in the first place, and their fear is no less important than mine,” he wrote.

He wants them to feel safe and welcome not just in school, but in society, and worries a signal has been sent that they aren’t. Elkind also reassured his students that a president alone can’t do many of the things that made the students afraid.

“At the end of the day, the sun will keep rising, the Earth keeps spinning, and life will continue,” he wrote. “We live in a democracy, and we need to honor the result of this election, but that does not mean we should not fight bigotry and for causes we believe in. I will continue to support ALL of my students whether they are Muslim, identify as LGBT, are female, or black, or Hispanic, or Native.”

The Student’s Aren’t Alone In Their Worry

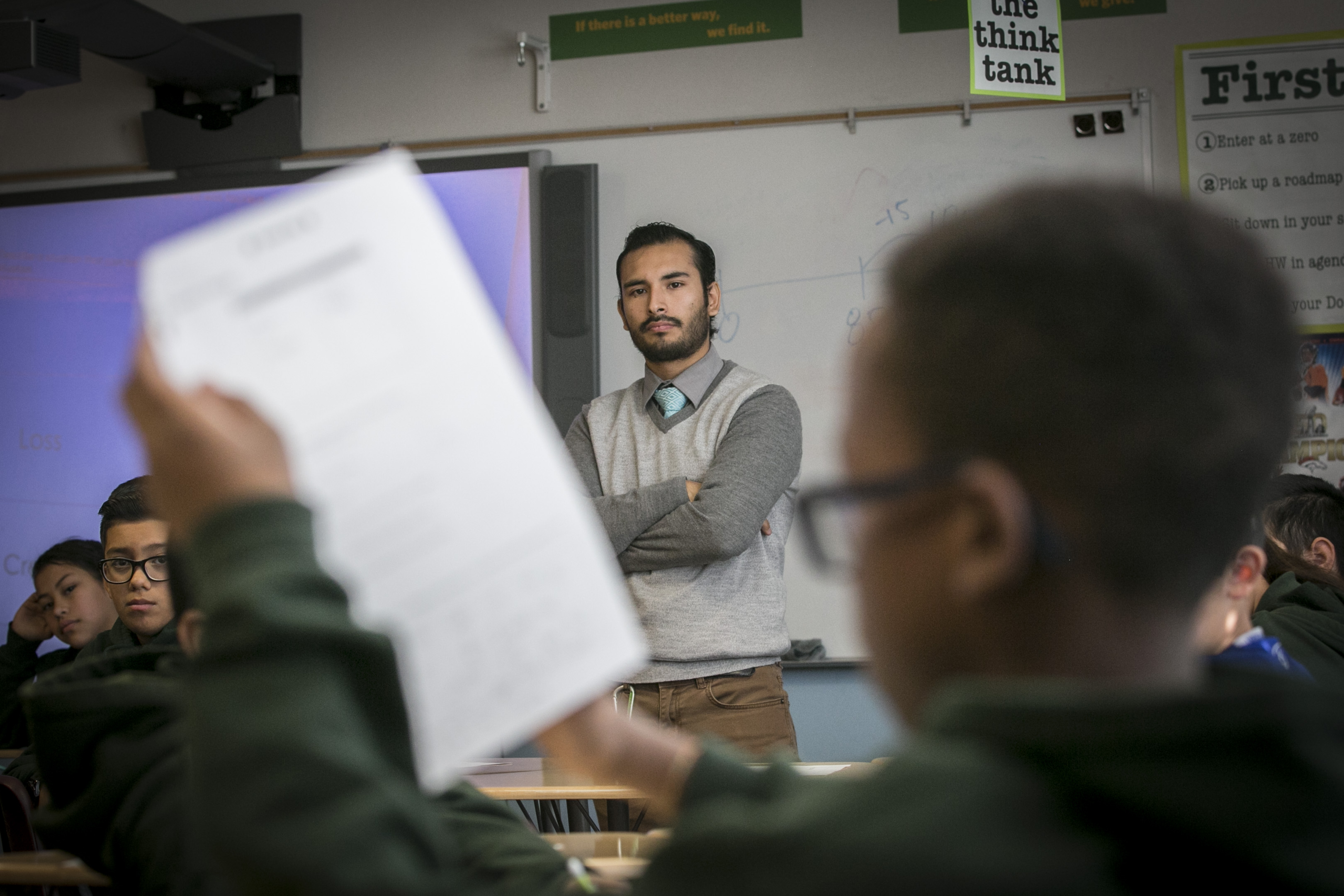

The day after the election, at KIPP Montbello College Prep, 6th grade teacher Alejandro Fuentes said a student suddenly ran into an open locker.

He recall asking him, “What are you doing?” The student’s reply, Fuentes said, was “Donald Trump won. I don’t want to be here, I don’t want to be at school. I’m not going to be paying attention anyway. What’s the point of being here when this was allowed to happen?”

As Fuentes taught math that day, he also tried to answer student questions about what a Trump presidency means for those who are Muslim or minority. He tried to reassure them, but was struggling himself.

“My students could tell that something was wrong with me because there were just tears in my eyes from the get-go,” he said. “And students kept coming up to me and asking me, ‘what’s wrong Mr. Fuentes, what’s wrong?’”

He told them that he is undocumented, arriving in the states at age five. Fuentes is living under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, granted to children who were brought here illegally by their parents. Fuentes said it will be hard for students to focus in the weeks ahead. And hard for him – until President-elect Donald Trump takes office – and starts to make policy.

“Come January, February, when he’s able to make decisions, I worry about being able to stay as a teacher, something that I’m passionate about and have done for almost four years,” he said. “And I worry about a possible deportation. That’s just an actual fear.”