Updated 9:45 a.m. -- Denver Public School officials will keep negotiating with the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, Superintendent Susana Cordova and the union said.

Updated 9:45 a.m. -- Denver Public School officials will keep negotiating with the Denver Classroom Teachers Association, Superintendent Susana Cordova and the union said.

Those negotiations would happen in advance of any decision from the state agency which authorizes strikes. The district formally asked for state intervention earlier in the week, which could delay a strike for up to 180 days.

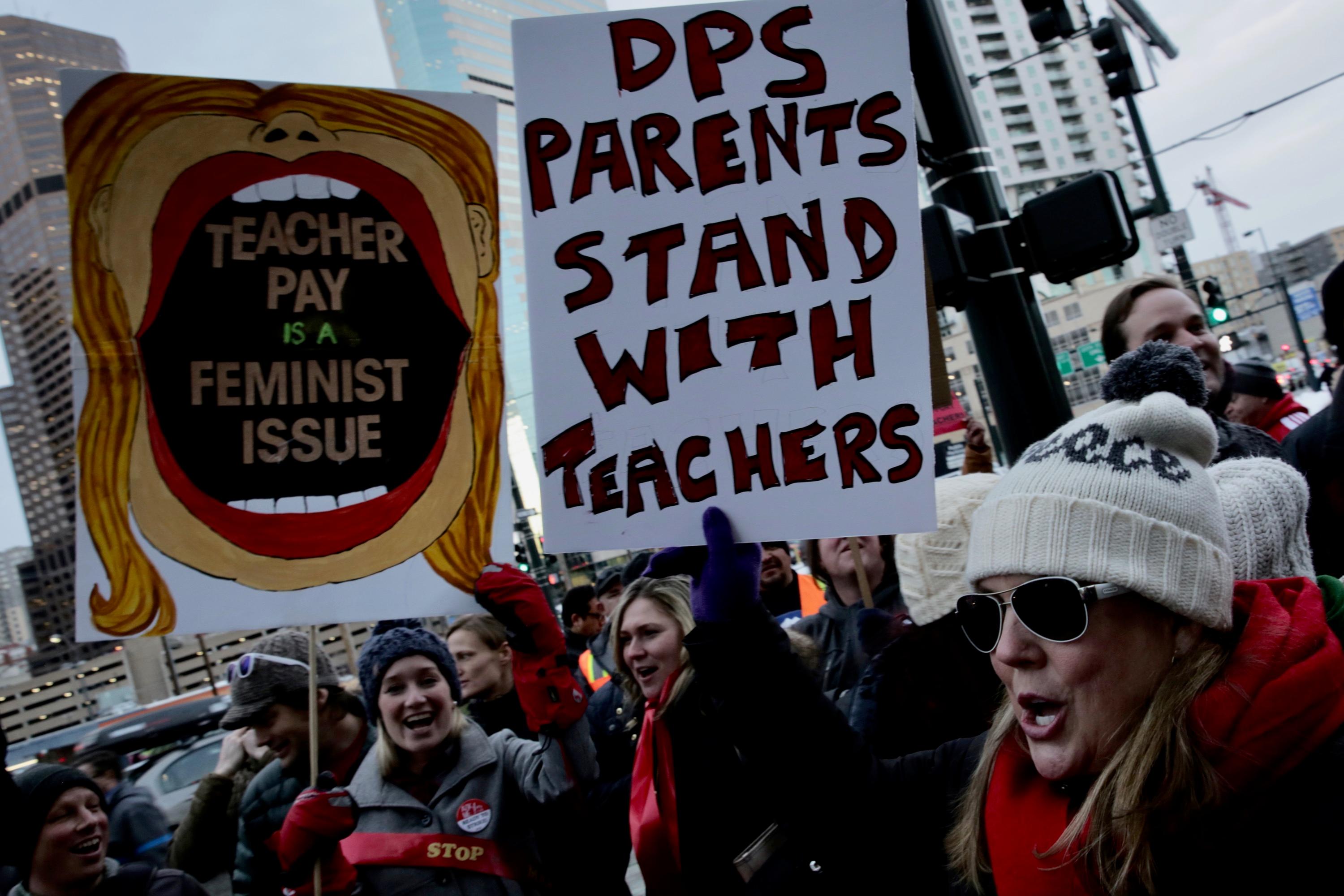

On Thursday night, DPS teachers and their supporters flooded a Denver school board meeting, describing their challenges with pay and imploring the state not get involved with the contract dispute.

"We have reached out to the DCTA and heard back today that we will continue negotiating," Cordova said Thursday. "We are now working out the details of when we will again meet so that we can continue working toward an agreement."

The union confirmed the district reached out. DCTA officials responded that they will resume talks as long as the bargaining is public and more money is part of the negotiations.

"The district needs to have a serious commitment to come to the table with more funding,” said union president Henry Roman on Friday. “Based on their last request to the governor to intervene, they stated very clearly that they have no new funding. To us that’s problem."

"As soon as they willing to bargain and put more money on table, we’re ready.”

A strike would affect 5,300 teachers and 71,000 students.

In a filing with the state, the school district outlined how the potential of a teacher strike in the state’s largest school district affects the public interest. The list includes loss of instructional time from teachers on strike, disruption of students’ ability to receive food and medical care services, as well as creating a financial hardship on DPS families.

Officials also are concerned that a "strike would deeply affect the culture of the schools long after the strike is over, including affecting the ability of the school district to hire teachers."

Some board members pointed the finger at state lawmakers, who have presided over budgets that have withheld nearly $750 million from Denver Public Schools since 2008.

"Enough is enough," said board chair Anne Rowe. "Let’s all join arms and let’s change the way we fund public education."

Board member Jennifer Bacon said the strike scenario is a chance to "reprioritize" for the district, including retaining teachers, getting teachers proper support in class and a livable wage.

"I think we can go back to the table," she said. "I don’t think we need the governor, I think we can figure this out," she said to the loudest applause of the night in a room packed with teachers.

The concern over state intervention stems from the delays it will cause. After the school district seeks state intervention, the education department has to ask the teachers' union to respond to the request. The union is expected to respond soon that it does not want the state to intervene.

That process could take up to 24 days, allowing 10 days for the union to respond and once they do, 14 days for the state to decide. If the state ultimately does get involved and use its limited power to try to broker an agreement, it could put a strike on hold for up to 180 days.

At the protest, and then inside during the board’s public comment period, people repeatedly and forcefully said the state should not intervene in the negotiations.

At the protest, and then inside during the board’s public comment period, people repeatedly and forcefully said the state should not intervene in the negotiations.

"Bringing in a mediator, bargaining for such an extended amount of time. Everything that could have been asked of us, we’ve done and so we’re just really feeling like it’s a district stall tactic," said teacher Anna Wallenkamp. She wants the district to bring a new offer to teachers.

Some in the crowded board room expressed worry over schools being staffed by substitutes, while others accused Cordova, the new superintendent, of continuing the "cycle of broken trust" between district leaders and teachers.

Rebecca Ryan, a teacher at Gilliam Youth Services Center, a youth detention center and Denver Public Schools site, said her "students are going to be put in danger, as is our staff, faced with inconsistency while our teachers fight for a fair wage."

Ryan, who is a single mom with three kids, needs the support of a food bank to help feed her children.

"My salary doesn't cover my student loans, my living expenses, and I now can't afford groceries," she said. "So, if you guys want to look me in the eye tonight, do me a favor. Look me in the eye, tell me why it is OK that you guys have all this money that you put in in central administration and I can't feed my children."

Several teachers, parents and students accused the district of having administrative bloat and excessive salaries for top administrators.

"We've been bargaining for 15 months," said East High teacher Anna Noble. "We don't need to have more meetings. We need a decision and we need it now."

"We feel like we've done everything. We've met the district. We've done our due diligence and it's falling on deaf ears" said teacher Eric Gallegos, explaining why teachers don't want state to get involved.

Students spoke about how worried they are about getting behind in their work, and not feeling safe with substitutes.

“It’s very scary that I am being asked to stop my hard classes while my teachers are fighting," said high school student Leilani Escalera. "I don’t want to be taught by someone I don’t know."