His story is at the center of a new book called "The Odyssey of Echo Company: The 1968 Tet Offensive and the Epic Battle to Survive the Vietnam War" by New York Times best-selling author Doug Stanton.

Read an excerpt:

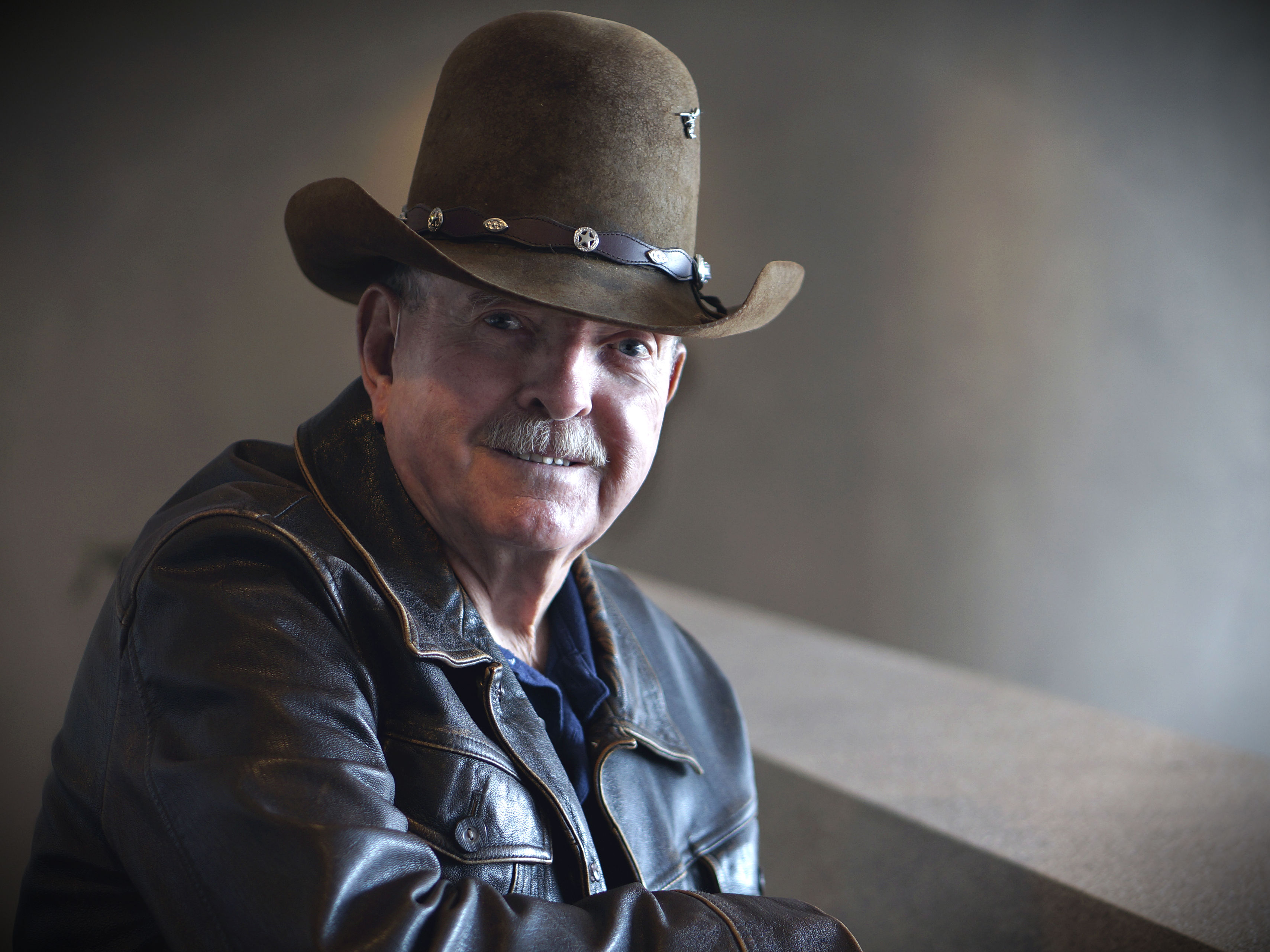

May 27, 2005 I first met Stan Parker in May 2005 when I was climbing into a Chinook helicopter on the tarmac at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan. I was trying to get to a U.S. Army Special Forces camp in Khost, on the Pakistani border. Wearing wraparound shades and a keffiyeh, Stan was older by at least twenty years than many of the soldiers I saw walking around the airstrip. He was in charge of air operations at Bagram Air Base, and this meant that he had charge of me. Unfortunately, the weather was not cooperating, and we weren’t flying anywhere. But fortunately for me, Stan Parker started telling stories while we waited. Short, sandy-haired, broad-chested, Stan had an easy smile and talked a lot like Robert Duvall in Lonesome Dove. He was wearing body armor, with an M-4 carbine slung across his chest. I wouldn’t want to mess with him. After thirty-five years of military service, he told me, he was finally thinking of “getting ready for retirement.” His had been quite a career. In 1993, he’d been in the Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia. He’d been part of the Special Forces operation in Honduras, the Philippines, Korea, and Eritrea, Africa. He’d been in gun battles in Afghanistan. When I asked Stan how many firefights he’d been in, he could not come up with an answer—hundreds, perhaps. He had achieved the rank of sergeant major and had been assigned to U.S. Special Operations Command, at MacDill Air Force Base, in Tampa, Florida. He was one of the Army’s senior elite soldiers, and, on top of this, he was deeply wired into America’s counterterrorism fight across the globe. He knew things. He’d seen things, he told me, “beyond a civilized person’s comprehension.” Yet when I’d asked him to name the scariest part of his military career, he said, “Coming home from Vietnam.” And on the day we met, that’s what Stan Parker really wanted to talk about: what had happened to him thirty-seven years earlier when he was twenty, during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Vietnam. 1968. January. Stan had read my book In Harm’s Way, and this had given him an idea. He’d seen that story about World War II, and the sinking of a Navy ship and the ordeal of its crew, as a survival story. Stan wanted to know if I would ever write about how he and his buddies had survived the Tet Offensive, when his forty-six-man Reconnaissance Platoon attacked and was attacked by well-trained North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong fighters. Stan’s odyssey had lasted ninety days, until he was wounded for a third time and forced to leave the intense brotherhood of his unit. A soldier awarded three Purple Hearts had no choice but to be shipped home. In order to stay in Vietnam, he’d refused the third award. (He was subsequently assigned to another unit.) I took Stan’s suggestion about writing this story and filed it under “Maybe.” I didn't think America was ready to hear that story while in the midst of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Maybe the country never would be ready. Part of this had to do with the age of the men who’d fought in Vietnam. Now in their late fifties and early sixties, they weren't old enough to want to talk, not just yet. In September 2012, seven years later, I gave a lecture to cadets and command staff at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, and I remembered that Stan Parker, now retired, lived nearby. We hadn't spoken in several years, and I called him. “I’ve been waiting for you,” he said, surprising me. “I’ve told my buddies about you. We’re ready. We want to talk about Vietnam.” The truth was that I’d never forgotten meeting Sergeant Major Stan Parker on that helicopter in Afghanistan. I still remembered the sunlight coming in through the green helo's rear ramp as this old soldier asked me to write about something that had happened to him and his Recon buddies years earlier, something that had affected them deeply and that they didn't understand. Tom Brokaw, he’d said then, was the only civilian who’d ever looked at his Combat Infantryman Badge with star and recognized that he’d served in Vietnam. Stan had met Brokaw a few months earlier on a helicopter in Afghanistan when he was reporting an NBC News special. Stan had been tasked as his bodyguard. He proudly showed me a photo of their meeting. Back in the late 1990s Brokaw had discovered the willingness of World War II veterans to unpack their secrets about their war as they turned seventy and felt perhaps that it was time to unburden themselves. Maybe, just maybe, I wondered, the same might now be true of the more than 2.7 million Americans who had deployed in Vietnam, 1.6 million of whom experienced combat or the threat of attack. Their average ages now ranged from sixty-five to sixty-nine. That’s a lot of people, I thought, a lot of untold stories. It seemed time for them to come home. • • • Even before he retired, Stan wanted to track down his former Recon 1/501 platoon-mates and ask them what they remembered. Some of them he found on the Internet didn't want to be reminded of the past and hung up when we called. He spent a surreal dinner with a former Recon member who made the nervous admission that he’d never told his wife that he’d served in Vietnam. He pulled Stan aside and begged him not to tell his family. Stan made up a fib that they once worked together many years earlier. This pattern of evasion troubled him. He wondered what it meant when a person couldn't admit that a major chapter of his life, perhaps its most potent and transformative moment, had ever taken place. And so Stan and I started to talk at great length over a span of several years. As with so many other stories about Vietnam, Stan’s would take a long time to tell. As he and I spoke, I occasionally saw a shadow in his eyes—call it memory, call it flashback. Something was there, traveling back and forth through his consciousness, unresolved. So many things, Doug. If I talk, I might be whole, I’ll be unburdened, I’ll be heard. I won’t be a better person, I know that, but I might be the person I am. Does that make sense? It does. I want to go on. Go on. Excerpted from THE ODYSSEY OF ECHO COMPANY by Doug Stanton. Copyright © 2017 by Reed City Productions, LLC. Excerpted with permission by Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. |

Related: