The first thing you need to know about Daniel Sharpe is that he grew up in a really small town of a few hundred people; Lake City on Colorado’s Western Slope. There he’d go to school, and the teacher would ask, “What do you want to do? What do you want to learn about?”

“The kids would say, ‘dissect something!’” Sharpe recalls. So they’d dissect. The next day they wanted to learn about physics, so the teacher says, “OK, let’s learn about fulcrums.”

One morning he and his classmates asked if, for gym class, they could climb a fourteener. The response? They said, “yeah, sure, no problem,” Sharpe laughs.

So that’s what he thought school was. A place where students can discover, go outside a lot and help make the decisions. Then he became a teacher in Denver.

He was suddenly part of a system with rules about what’s taught when and how. A system where the children weren’t engaged, where teachers were watching the clock and he was left feeling like the career that he picked was “kind of lame.”

It’s a system he wanted to improve.

“How can I maybe make some changes so that I can bring some of what I experienced growing up into a larger traditional public school?”

Daniel Sharpe and others say it’s a lot harder to innovate in the classroom than it is to teach in a traditional style of delivering information in front of a class. Consultant Christina Jean says it requires a change in classroom power dynamics so you’re “not wrangling a whole group of kids and making them sit still and listen to you for long periods of time anymore.”

In addition to giving up some classroom control, another piece of the puzzle is teachers themselves getting the “emotional space to be vulnerable and try new things and take risks,” says Tara Jahn, a former teacher who is a consultant on innovative teaching. Afterall, there’s still evaluations and testing to be concerned with.

Enter SpaceLab, a project of the nonprofit Colorado Education Initiative. The goal is to provide a space to help teachers design the future of learning. There are networking sessions, “seeing is believing” innovative classroom tours, and design thinking workshops. Design-thinking is a problem-solving approach that helps educators identify a problem in their schools and then design solutions for the person at the center of it, usually students.

Barriers to change run the gamut: Lack of resources, helping students with mental health needs, pressure to perform on tests, initiative fatigue, adversity to change and teacher shortages. A big one is stress. Teachers in the lab workshop generated dozens of sticky notes naming all the problems they face. Participants then built creative confidence to work on those challenges and to shake things up in their school or classroom. Several of the participants zeroed in on a goal to give students more control over their own learning.

Based on his own childhood experiences in school, Daniel Sharpe is already ahead of the teachers in the SpaceLab project. Now an administrator at McGlone Elementary in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood, he decided several years ago that students needed to be more involved.

McGlone is one of Denver Public Schools’ Imaginarium innovation labs. These schools are centered on reinventing education, either through technique or physical spaces.

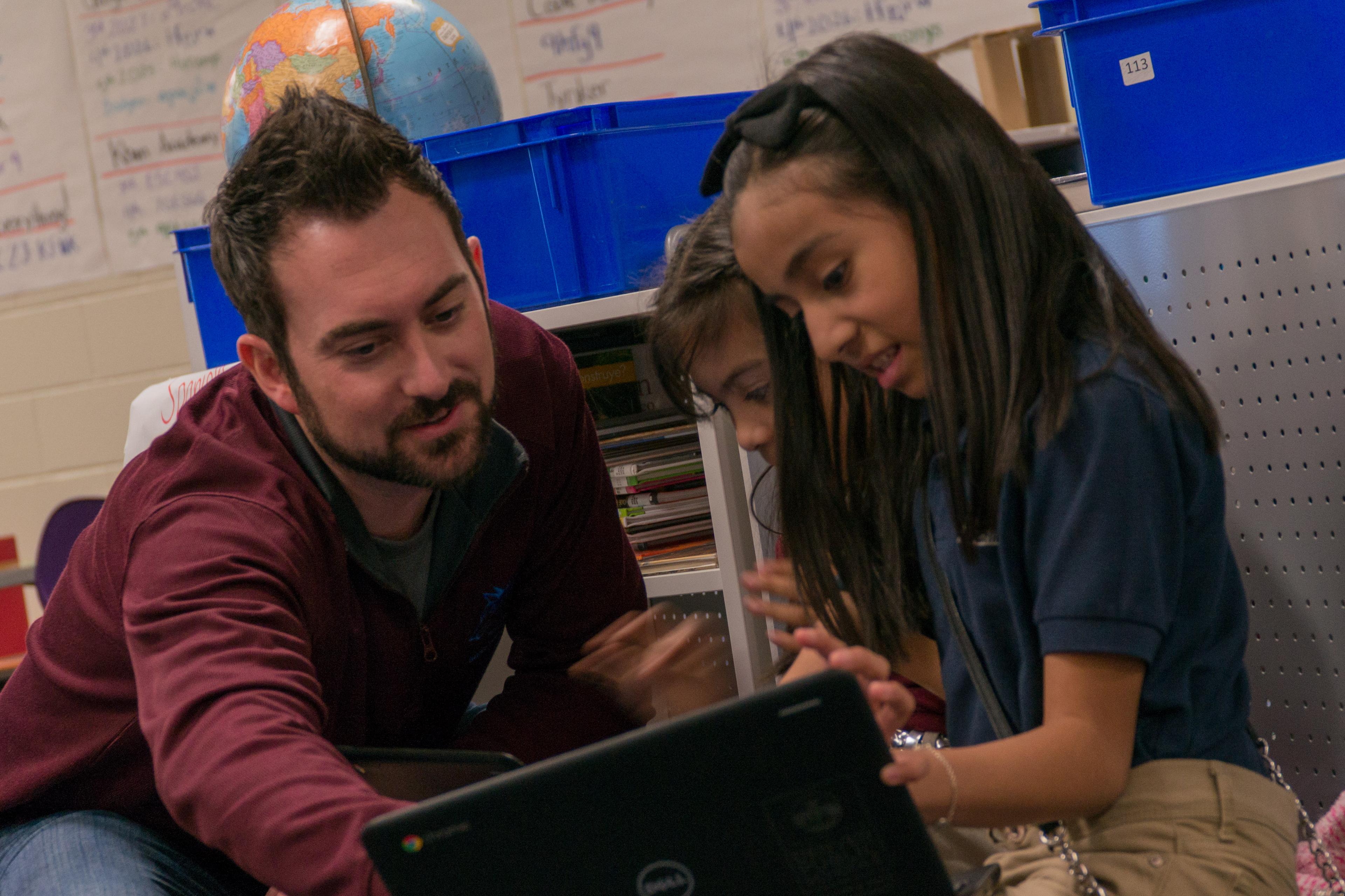

Using digital media Sharpe let students control their pace and path of learning. Together, they developed a computer platform tied to Colorado’s academic standards. They found games for each standard and chose what to work on. Sharpe would help keep them on track.

“You could just see the excitement rise because kids had more freedom around what they were choosing,” he says.

Sharpe communicates with networks of teachers online trying to push the envelope. They share ideas and try new things. Students earn “digital badges” as a way to recognize them for things that aren’t captured in grades.

But innovation isn’t just about using technology in new ways. A visit to a school in San Francisco pushed Sharpe to think about creating project-based learning cycles. At another conference, educators from Argentina pushed him to think about why schools even have grades.

“Why are we so held back that we think that kids have to learn this skill at this point, this skill at this point, this skill at this point?” he wonders.

Bruce Hankins, the superintendent of Dolores County Schools, thinks he knows why.

He says the name for it is “the giant hairball,” what one corporate creativity expert calls the tangled mass of rules, traditions, and systems that bog down organizations. It keeps educators from breaking down classroom walls and trying new things.

He realized he got sucked into the hairball and has been shocked by how standardization in education “stifles creativity, and how it stifles collaboration, and how it stifles empathy.”

Hankins attended the SpaceLab workshop. There he learned that developing empathy for his students was the first step to bringing more of their voices into school. Hankins decided to shadow a student, named Faith, for a day.

As the stand-in for a typical Colorado high schooler, Hankins found that Faith got up around 6 a.m. to attend school where she “was lectured at” for most of the day. She had sports practice until 5:30 p.m., skipping dinner with her family to do several hours of homework afterward. Later, it was off to bed around 11:00 p.m. only to get to sleep around midnight.

It’s about a 17-hour day.

“No wonder our kids feel so much stress,” Hankins says. By the end of Faith’s day he saw “an adult-centered culture. Not a kid-centered culture.”

Since the world needs kids to solve complex problems collaboratively, resolve conflicts, think outside the box, know the world around them and be empathetic, Hankins says schools can’t afford to be adult-centered. He’s working on ways to create time and space to bring kids’ voices, choices, needs and desires into the school day.

Hankins eventually wants to tap students to speak at teacher trainings; he’s invited others to be advisors to the Board of Education. During afternoons at the 7th Street Elementary school in Dove Creek, Colorado, you’ll find kids working on projects rooted in the community.

Hankins has another wish: that every teacher and administrator in his district shadow a student for a day.

“Take some time to see your job through the eyes of kids,” he says.

It’s a powerful way to make teaching exciting again and – just as Daniel Sharpe experienced growing up in small-town Colorado and now preaches at McGlone — give students the voice they crave in their education.

What Do You Want To Know?

Questions about innovation in education? What has worked to prepare your child for today’s world? Know a teacher that’s breaking through? Leave a question or suggestion in the comments below, tweet us @NewsCPR or @CPRBrundin or email us at [email protected].