How schools are funded in Colorado is so complex, there’s a joke that only five people in the state truly understand it.

Superintendent Jan DeLay in northeastern Colorado’s RE-1 Valley School District is on a mission to change that. She’s convinced that once average citizens understand why so many districts like hers are in a fiscal crisis, they’ll approve a local tax measure on the ballot to fund RE-1.

The money would be would be used to attract and keep teachers and to expand academic opportunities for students through technology, textbooks and other programs.

The last time the district passed a mill levy was in 2005, for $500,000 to update buildings, technology, textbooks and transportation. DeLay says that money is gone within the first couple of months in the new school year.

“What we have to do is decide, ‘OK, so are we going to buy science materials for our science teachers this year’ and then … ‘do we have money left over for a bus or if we have internet connectivity problems’ – your switches, which is the backbone of your internet service – updating our switches is $200,000, a bus is $100,000, so you can see how quickly $500,000 goes.”

"Unsustainable" Finances

DeLay has one word to describe her school district’s finances: “unsustainable.” Yet she knows it will take more than a word to convince the public her schools need more money.

DeLay’s nights and weekends have been spent with community groups. They stare quizzically at her slide show of charts and graphs and buckets. She doesn’t have a choice, really. That’s because RE-1 Valley is one of two Colorado districts so far that have declared “fiscal exigencies.” That’s a fancy way of saying there’s simply not enough money to support the schools and cuts had to be made.

“Now that I know the state isn’t going to pick up and help us, I’ve got to let people know about this,” she says.

RE-1 Valley Cost Cutting

DeLay tells the district’s story to anyone who will listen. Today it’s the League of Women Voters. The more people who understand how the district got to this place, the more she believes she can build momentum for a $2 million ballot measure. Which, by the way, is the same amount that the state cut from what it gives to the district.

“We’ve made cuts in athletics, we’ve made cuts in teachers, we’ve made cuts, in our administrative staff,” DeLay says, running through a list of cost-cutting that includes textbooks, reducing paper use and buying used school buses off of the internet from Oklahoma.

She’s also trying to get the public to see how hard it is to hang on to teachers with salaries starting around $30,000.

“The perception is that you live here, you make what other people make here, but what we’re dealing with is competition from other districts and across the nation,” DeLay says.

Unpaid 'Credit Card Debt'

RE-1 Valley isn’t alone. Dozens of other Colorado districts are going to voters in November to ask for more than $4 billion to make up for state funding cuts. But rural districts have had a tougher time at passing local measures. DeLay is open to suggestions from the group.

“If you do think we should go forward with this, how do we explain some of these things to our voters, to our constituents out here in northeastern Colorado who are very conservative, who don’t like government?”

DeLay throws everything at this small group and it’s a lot to absorb. First, average funding per student in the nation is $11,667. Here it’s $6,703.

A lot of other things are happening, too. Kids from farm families are growing up and moving away. Each kid lost is $6,703 gone from the district. Enrollment has declined by 644 students since 1996. And even at 2,098 students, the district isn’t small enough to qualify for an extra $2,000 per student that the smaller district next door, Buffalo RE-4J, gets. She’s lost students to that neighboring district.

The main problem facing all of Colorado’s 178 districts is the loss of state funding.

“They [the region’s lawmakers] referred to this as credit card debt,” DeLay says.

Desperate to balance the state budget during the Great Recession, state lawmakers began slashing school budgets for about $5 billion. They promised they’d pay it back.

“The problem the state still doesn’t have enough money to pay that back because of our increased burden with Medicaid,” she says.

For RE-1 Valley, that’s meant a couple of million out of the budget every year since 2010.

“It’s about 12 percent of an annual cut to most school districts, 12 percent of our budgets,” DeLay says.

A woman in the small audience looks confused.

“I’m sorry why?” she asks.

DeLay is patient. This stuff is hard. Partly because of a very complex school finance system and conflicting constitutional amendments. The reactions at her community gatherings vary.

“Sometimes it’s just stunned silence,” she says. “Sometimes it’s an invigorating mood in the room saying, ‘how can we help, what can we do?’”

Checking In With Voters

Backers of the property tax increase have their work cut out for them.

As state Sen. Jerry Sonnenberg says, his “district is one of the most conservative districts in the state.” He reflects a distrust of government in these parts, of which public schools are part.

“We grow government every single year as much as the law and TABOR allows us to grow it,” he says, over dinner at the River City Grill in Sterling. “We don’t have income problem in this state, we have a spending problem.”

This is when Sonneberg is his most animated. He believes Colorado never should have agreed to a Medicaid expansion, which is consuming greater portions of the state budget. While he grouses about spending, he’s also upset about Colorado’s complex school funding formula that makes “schools like Cherry Creek get more money than a school like Sterling. Now that’s unreasonable.”

Cherry Creek Schools, located in suburban Denver received $6,982 per pupil from the state in 2015. RE-1 Valley received $6,703.

Sonnenberg says the school finance formula needs to be fixed. His district encompasses a more than a fourth of the 178 school districts in the state. He says there’s no question more money is needed in schools.

“It’s clear that there are other things driving the budget and education’s not the priority I think it needs to be,” he says.

But voters are also grumpy about taxes because they feel they were sold a bill of goods on the marijuana legalization ballot measure. Alan Barton is finishing up his dinner at a table nearby Sonnenberg’s.

“I thought when we voted on the marijuana proposition that the taxes were going to go to the schools?” he says. “And nothing has been seen from that.”

In fact, a small sliver of taxes is going to a small sliver of schools, for school construction and only if a district comes up with a matching grant.

“I think obviously we got smoked by fine print on this last one and things need to be more clear,” Barton says. “Politics is too fogged over.”

Barton’s wife though, says she’d vote for a mill levy override.

“If it goes to the schools, yes,” she says.

Many farmers are also wary. A young farm family is at a table nearby. The father, Justin, doesn’t support the tax increase. He doesn’t want to give his last name because he does business in this small town and worries about offending clients and others. The property tax increase on the ballot here would cost the average homeowner $72 a year. But if you’re a farmer who irrigates with sprinklers it will cost you $340.

Justin says that farmers “don’t want to pay any more taxes” and that there’s “waste” in schools.

“There’s a lot of wasted money spent on a lot of frivolous things, sports are maybe too important, ahead of curriculum. That’s one place that maybe could be worked on,” he says.

But even Sen. Sonnenberg, a fiscal conservative and a farmer, says that when it comes down to it, rural schools are the centers of the community. Everyone turns out to watch the sports teams.

“If you give people an option and say this what we’re going to spend the money for, people of Logan County– would you vote for more taxes for the school district, if you give them a solid reason, there is no question they would vote for it,” he says.

Using Props To Make A Point

RE-1 Valley Superintendent Jan DeLay is ready for any questions voters have about waste.

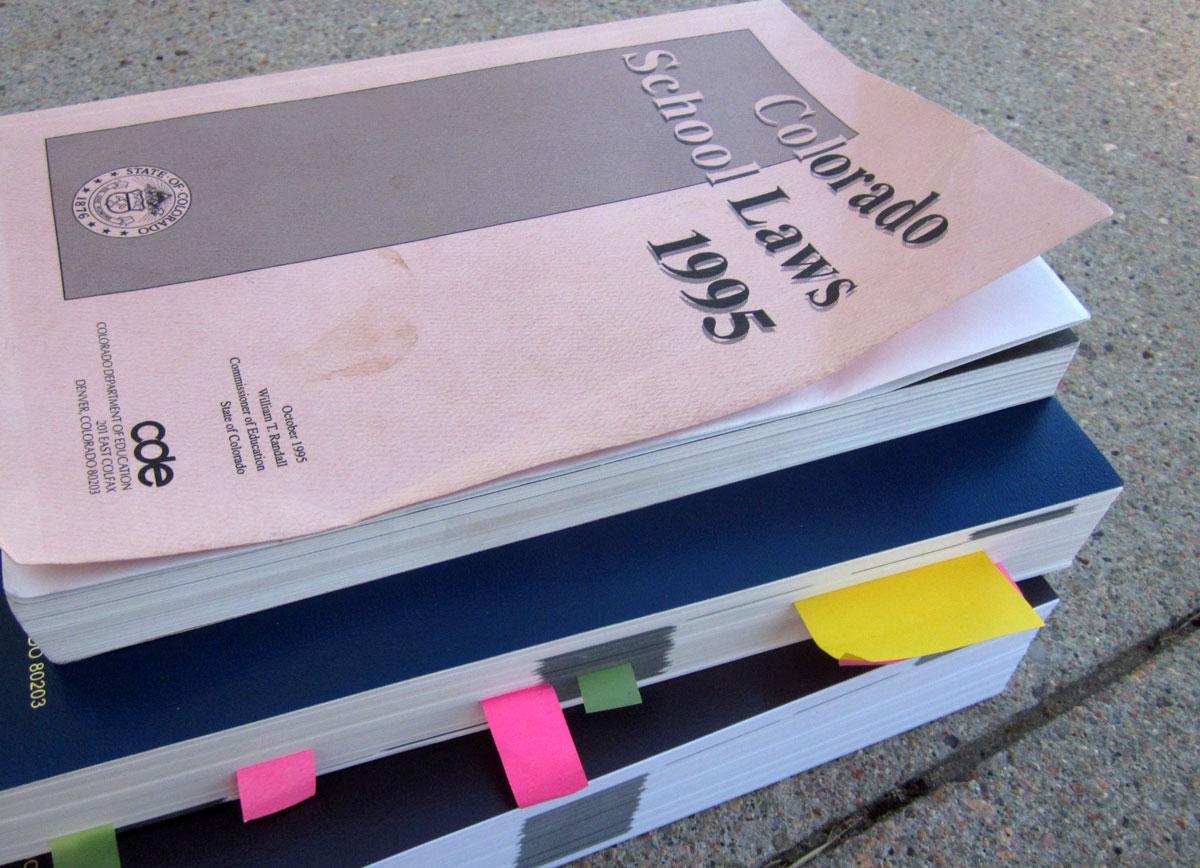

She uses props to tackle the criticism that, ‘school districts have just too much fat in the central office.’ Not so, says DeLay. That budget has been cut to the bone, to the point where there’s no staff to file and track everything required by state law, which has got the district into trouble and cost more money. She starts by holding up a thin book of school regulations and accountability laws schools must follow.

“Colorado school laws 1995,” she says. “Pretty small book. Smaller than a bible.”

Then she holds up another. A well-worn book and much thicker.

“School laws 2012,” she says. “Hmm… Maybe a good-sized bible.“

And finally, a much bigger book.

“School laws 2015,” she says. “Much larger than a bible.”

While the state was slashing budgets, the regulations, the requirements for reporting to the state about new laws like teacher evaluation, school accountability, academic standards, new early grades reading laws have all increased. Aside from these hidden costs, schools across Colorado are also grappling with rising health care, retirement and transportation costs.

“And that doesn’t come with any extra money, we’re just required to do it,” DeLay tells the group.

“We don’t have the ability to raise tuition and so these kinds of things – even increases to minimum wage, there’s no money attached to a public school to be able to generate that kind of revenue.”

At the end of her presentation, DeLay’s million dollar question is “how do you explain such a complicated funding mechanism to John Q. Public?”

The group doesn’t have many suggestions. It’s kind of overwhelming. Jean Williamson thinks it was a good presentation.

“I think the biggest problem is that nobody really understands the tax situation in this state including me,” she says.

Williamson suggests teaching kids in schools about how public school finance works.

Now that the measure is officially on the ballot, Superintendent Jan DeLay can’t campaign for it. She is allowed to continue her quest to help the public understand the murky world of school finance and why her district can’t keep moving forward unless citizens step up to replace the state’s unpaid credit card debt. Sometimes, it’s a solitary quest.

“That’s just when I have to dig deep and say, you know what? Superintendency is lonely sometimes but that’s what I wanted to do so buck up!” she laughs.