Eleven-year-old Gitanjali Rao became concerned about lead in drinking water two years ago, when she learned of the crisis in Flint, Michigan. And it’s not just Flint, says the student from the Denver suburb of Lone Tree, approximately 5,000 water systems in the U.S. have problems with lead contamination.

Eleven-year-old Gitanjali Rao became concerned about lead in drinking water two years ago, when she learned of the crisis in Flint, Michigan. And it’s not just Flint, says the student from the Denver suburb of Lone Tree, approximately 5,000 water systems in the U.S. have problems with lead contamination.

The seventh grader at STEM School Highlands Ranch told Colorado Matters that troubling statistic was on her mind when she heard of the Discovery Education 3M Young Scientist Challenge, a national competition for middle schoolers to find innovative solutions to everyday problems. This month Rao won that competition, and a $25,000 prize, for a lead-detection device she invented.

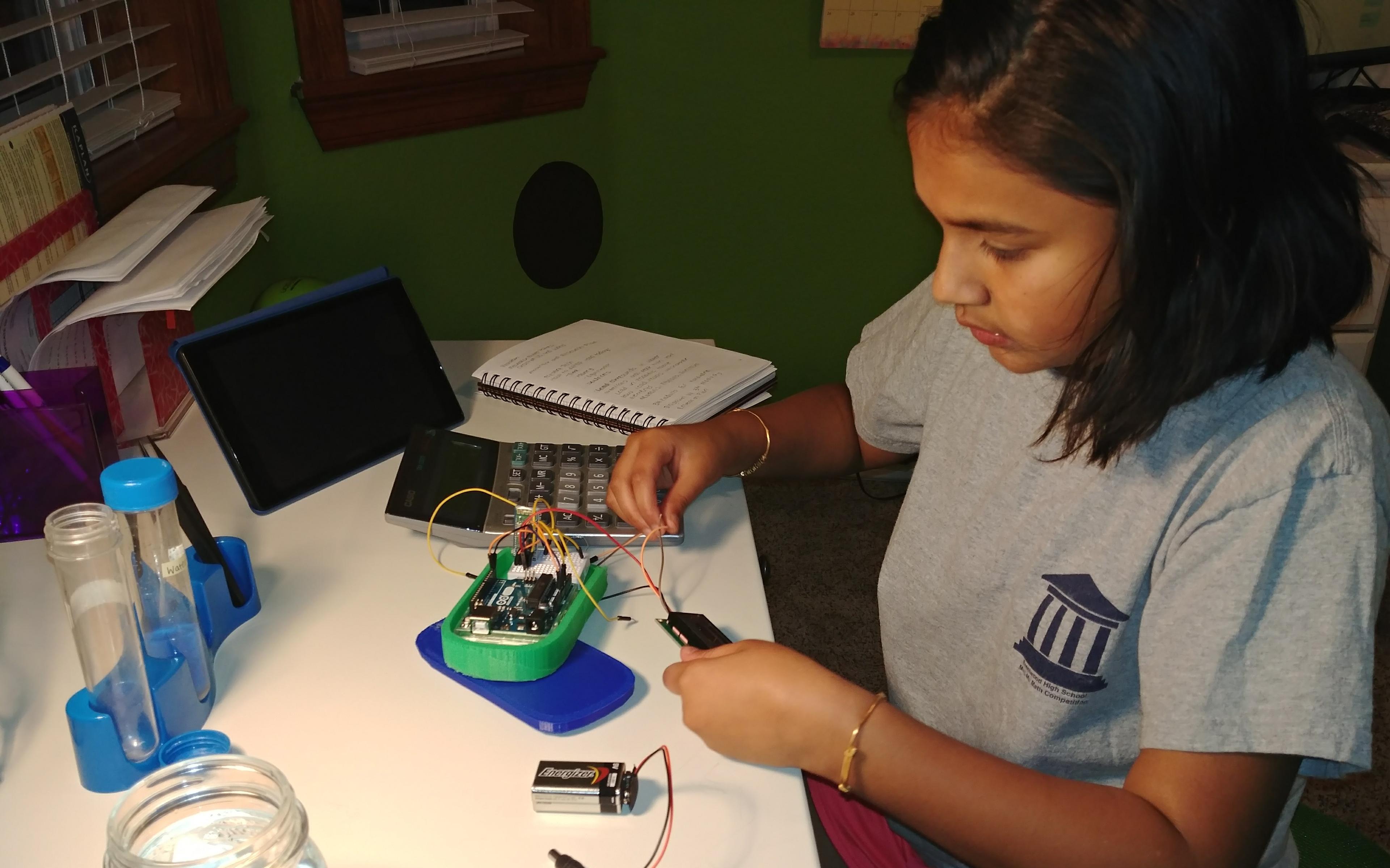

Her device is called Tethys, named for the Greek goddess of fresh water. "It includes three main parts," she says. "A core device, a housing processor with a Bluetooth extension, a 9 volt battery, and a slot to enter a disposable cartridge. And it all connects to a Smartphone.

On how she got started:

"So I've been following the Flint water crisis for about two years now. I thought about creating a device when I saw my parents testing for lead in our water using the test strips. I realized that it wasn't a reliable process. I wanted to do something to change this, not only for my parents, but for the residents of Flint and places like Flint around the world. ... There are two main ways to test for lead in our water or just water quality in general. One is the test strips, and the other one is sending our water off to the EPA. The test strips, on one hand, are easy to use and fast. But they're not accurate. And sending our water out to the EPA is accurate, but it's expensive. It requires expensive equipment and it's time-consuming."

On the role of her mentor:

"My mentor helped me originally with introducing me to nanotube simulation using an application online. This allowed me to experiment with lead within the carbon nanotube itself."

On the role of her school and teachers:

"Yeah so I got a lot of help from my school, STEM School Highlands Ranch. First of all, they helped me 3D print the outer cover of my device and my cartridge. This allowed me to keep all my parts within the device intact. One of my other computer science teachers helped me develop my user interface further, making it more user friendly, of course."

On what she'll do with the prize money:

"With most of the money, I plan to continue evolving my device so that it can be put out into market, and it can be in everyone's hands. With the rest of the money, I plan to give back to the organizations I volunteer for, such as Children's Kindness Network. I would also like to put the rest into my college fund."

Full Transcript

Ryan Warner: You're with Colorado Matters from CPR News. I'm Ryan Warner. An 11-year-old from Lone Tree is America's Top Young Scientist. Gitanjali Rao earned that title by inventing a new test for lead in drinking water. She has won $25,000 in this young science challenge. Gitanjali, welcome to the program. Gitanjali Rao: Thank you for having me. RW: This contest asks kids, fifth through eighth grade, to solve an everyday problem. What inspired you to work with lead in water? GR: So I've been following the Flint water crisis for about two years now. I thought about creating a device when I saw my parents testing for lead in our water using the test strips. I realized that it wasn't a reliable process. I wanted to do something to change this, not only for my parents, but for the residents of Flint and places like Flint around the world. RW: This means you started paying attention to the Flint crisis when you were about nine, I gather. GR: Yes. RW: Wow, OK. Right now, if you want to test your water, what, you buy these strips? What doesn't quite work about them, do you think? GR: There are two main ways to test for lead in our water or just water quality in general. One is the test strips, and the other one is sending our water off to the EPA. The test strips, on one hand, are easy to use and fast. But they're not accurate. And sending our water out to the EPA is accurate, but it's expensive. It requires expensive equipment and it's time-consuming. RW: Your invention is called ... say it for me. GR: Tethys. RW: Tethys, after the Greek goddess of fresh water. Is that right? GR: Yes. RW: And you've got one here. This is a plastic box smaller than a breadbox. I don't know who has breadboxes anymore. But briefly, how does it work? GR: It's a very simple process. It includes three main parts, a core device, housing processor with a Bluetooth extension, and a 9 volt battery, and a slot to enter a disposable cartridge. RW: And this connects to your Smartphone? GR: Yes. Yeah, and it connects to your Smartphone to display the results of safe water status, slightly contaminated, or critical. So you just attach a disposable cartridge to the device itself and dip the cartridge in the water you wish to test. Once you do that, you pull out your Smartphone, and connect over Bluetooth, and check your status. RW: OK. Do you think this would be very expensive if it were offered on the market? GR: Right now at this point, it is only $20 and once it's manufactured at scale, that pricing significantly reduce, as well. RW: You know what impresses me, Gitanjali, is that you can speak to all kinds of audiences. I feel like you are explaining very clearly here in everyday terms how this works. But you had to submit this idea in a video, and that was to a different audience. That's to the folks at the contest. I have to just play a bit of your video here. GR: My solution proposes using nanotube based sensors that detect the presence of lead and its compounds. Due to the sensitivity and connectivity of carbon atoms structures, this sensor can detect lead faster than any other current techniques. RW: Why are you talking so fast? GR: I had to smoosh a lot of information into one to two minutes. RW: And you had to get in a lot of science. You had to demonstrate to the judges that you knew what you were talking about. GR: Yes, I did. RW: From that video, you were selected as a finalist and assigned a mentor, Dr. Kathleen Shafer, who works at 3M, the company that sponsors this National Young Scientist contest. What sorts of things did she help you with? GR: My mentor helped me originally with introducing me to nanotube simulation using an application online. This allowed me to experiment with lead within the carbon nanotube itself. RW: And so not to be exposed to it, right? GR: Yeah, yeah. She also helped me refine my experimentation plans and make sure I had all the safety and disposal requirements into consideration, as well, since those are also important aspects. RW: Can you tell me what a nanotube is? GR: Yeah, a carbon nanotube is a tube-like structure made out of carbon atoms, and they have unique connectivity and connectivity properties in general. They're measured in one billionth of a meter. RW: That is what makes them nano. You put the Tethys together, and you needed the types of tools that scientists have, like a lab, and even a 3D printer. I'll say that you're a seventh grader at STEM School Highlands Ranch. You went to your teachers. What did they think? How did they help? GR: Yeah so I got a lot of help from my school, STEM School Highlands Ranch. First of all, they helped me 3D print the outer cover of my device and my cartridge. This allowed me to keep all my parts within the device intact. One of my other computer science teachers helped me develop my user interface further, making it more user friendly, of course. RW: That's the app, in other words, the user interface of the app, so that it makes sense to people. GR: Yeah. One of the high school chemistry teachers allowed me to use her chemistry lab in order to perform my tests. RW: It takes a village to raise a lead test kit, I suppose. The end result is that you won $25,000. What are you going to do with that money? GR: With most of the money, I plan to continue evolving my device so that it can be put out into market, and it can be in everyone's hands. With the rest of the money, I plan to give back to the organizations I volunteer for, such as Children's Kindness Network. I would also like to put the rest into my college fund. RW: Into college. You're so sensible. What do you think you'll study? GR: I want to go to MIT to study genetics and epidemiology, since they allow me to look at different approaches to solve real-world problems out there today. RW: Sounds like you've prepared that answer. Someone has asked you that before, I can just tell. Do you think that you might be on Shark Tank some day pitching this lead test kit? GR: I really hope that someday I'll be on Shark Tank. At this point, I'm trying to focus on making sure that my results are accurate. But once it becomes commercially available, that could be a very real possibility. RW: Yeah, and I guess this whole project has really made you just think of your own water. GR: Yeah, yeah. I had to try to the test strips while I was developing this project. It showed light marks, and it wasn't very clear, since most of the test strips work on chemical reactions. So while I developed this device, it made me think of, is my water clean? RW: Is it? GR: It is. RW: OK, I'm pleased to hear you're drinking clean water. Gitanjali, thank you for being with us. GR: Thank you! RW: She's Gitanjali Rao, a seventh grader at STEM School Highlands Ranch and her invention of a lead detector won the National Discovery Education 3M Young Scientist Challenge. You're with Colorado Matters from CPR News. |