Carl and Brenda Dutro have spent their entire married life together in the same home on a corner lot in the Eastern Plains town of Hugo. For 30 years they ran the only grocery store in town, Osborne’s, before they retired.

They were looking forward to some fun. There’s family, especially grandchildren. Carl thought he’d spend more time with his true passion: a full blown music recording studio, festooned with posters of the Beatles and the Broncos, and scheduling performances with a friend. On one recent day in early May he was picking out the intro to “Dear Prudence” on his guitar.

But other matters — health matters — intruded. Brenda said that ever since the Affordable Care Act went into effect, they’ve struggled not to get dropped by their insurance company, and their monthly premiums have skyrocketed.

“I think ours jumped from $700 to $1,700” over the course of three or four years,” she said recently, talking at her kitchen table. “What they should really call it is Non-Affordable Care Act.”

Last year Carl was hospitalized with blood clots in his lungs. The bill came to $11,000. Insurance only covered a third and they’re using Carl’s monthly social security check to help pay off the rest. They say the whole health insurance system is a mess, and believe the government is a primary culprit.

Even though Carl is 64 and Brenda is 62, they’ve decided to go without — to drop their health insurance all together. They’ll take their chances, at least until Carl qualifies for Medicare when he turns 65. Brenda describes a recent phone call with their insurer, Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield.

“It's very emotional because it's like ‘What do we do? How do we fix this?’ You know, and the one lady said ‘Well I think that sounds high. Let me see if we can get you a cheaper rate.’ And she said ‘That's the cheapest we can have.’ She said ‘Can I ask why you're dropping? I said ‘Yeah we can't afford it. I said it's too much.’”

Their predicament is a common one in rural areas.

After the reforms of the Affordable Care Act, Colorado’s uninsured rate dropped significantly, from 14.3 percent in 2013 to 6.7 percent in 2015. Roughly 500,000 people in the state gained health insurance coverage. About 400,000 people got covered through expanded eligibility of Medicaid, the federal health care program for low-income families or individuals.

But the vast changes brought by the ACA ushered in a period of sustained turbulence for insurers. Since 2015, we’ve seen insurers drop out of Colorado’s exchange, and prices rise. Insurance rates shot up by 20 percent for customers on Colorado’s individual insurance market in 2017. What’s more, residents in 14 Colorado counties were left with just one carrier offering plan through Connect for Health, the state's insurance exchange. The hikes were the biggest since the launch of the ACA and in some rural parts of Colorado, premiums spiked by 40 percent.

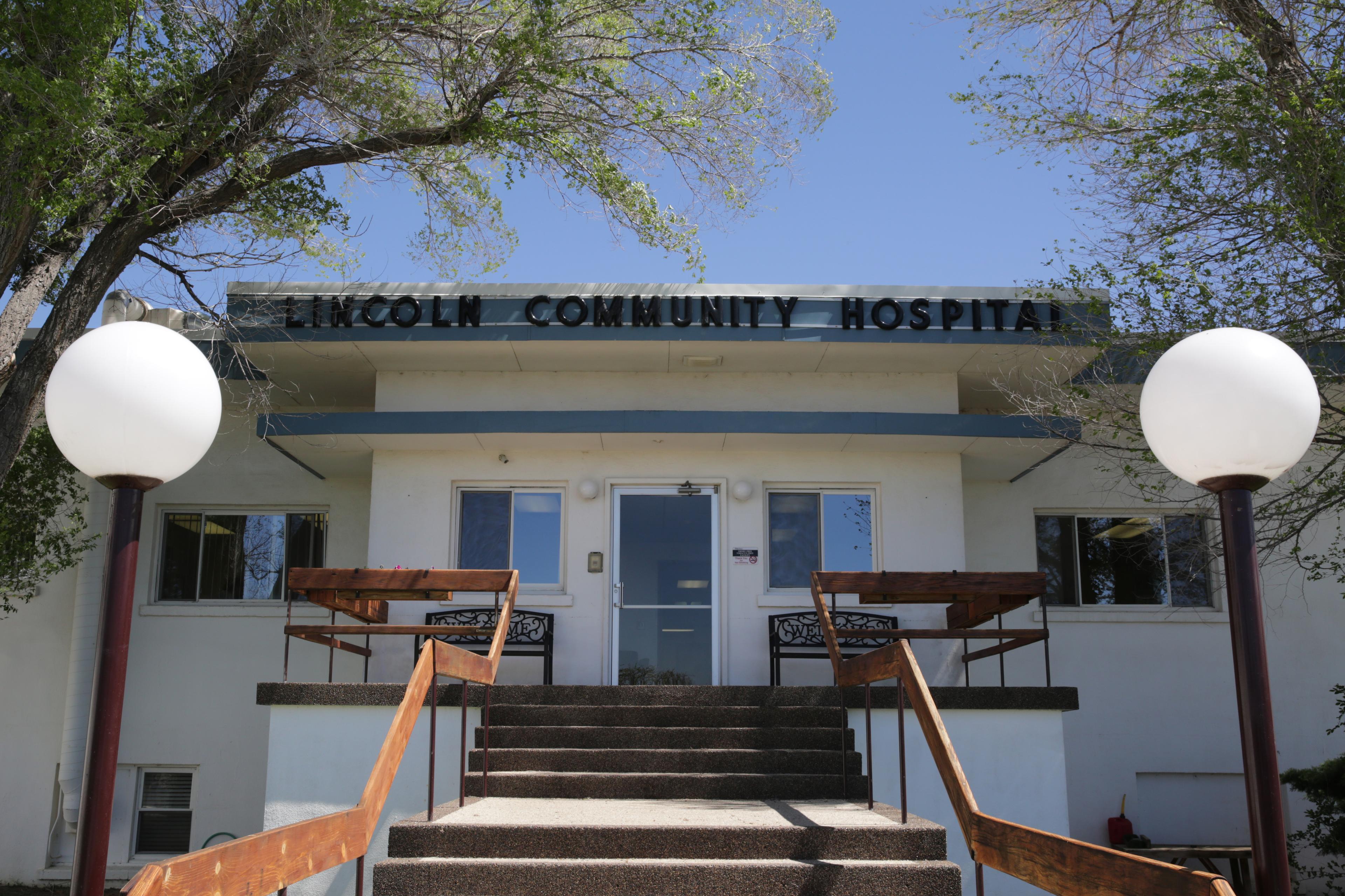

Medicaid is in now the crosshairs of Congressional Republicans. Their initial Obamacare replacement plan contains deep Medicaid cuts. That could mean cuts to recipients and hospitals like Lincoln Community Hospital and Care Center in Hugo.

“I don't know why everybody thinks the government has to control our lives,” Carl Dutro said. “It just seems like when the government gets a hold of something, they can screw it up and make it three times more expensive and it doesn't to a point work. And I think that's what we're finding out with Obamacare, it's going to explode.”

Lincoln County is Trump Country: Seventy-eight percent of voters here, including the Dutros, voted for the Republican nominee. And they say they’re looking to the president to improve things.

“Hopefully he can do something to turn this situation around,” Brenda said. “We’ve got to pull together.”

That sentiment rings true with Justin Carter. He is 35, a father of six, an auto mechanic and a volunteer firefighter. As he and a couple of other firefighters loaded 20 racks of ribs into the VFW Hall for the town’s annual fundraiser, he explained that he voted for Trump to fix health costs.

“If we can get the healthcare under control that would be phenomenal, especially for a small community like ourselves. I mean any break that we can get, it would be phenomenal.”

Carter works at Parmer’s, the town’s only automotive shop. He splits his insurance costs with his employer, but said his premiums have been going up and up. He likes that Trump is a businessman and hopes he can use those skills to rein in runaway health premiums.

“I mean, he’s a bulldog and hopefully we can stop getting bullied, the middle class, and you know start living a little better, instead about worrying paycheck to paycheck. And being insurance poor, as I like to call it, you know, paying so much for insurance.”

Just up the street is the Lincoln Community Hospital, the only hospital in this county of 5,500 people. A dozen small birds, finches, act as greeters in the lobby of its long-term care center.

Most of the 29 elderly residents here are on Medicaid, the federal health insurance program for low-income Americans. One of them is 67-year-old Carleen Theel. The former elementary school teacher likes living in a small-town care center.

“I’ve always been in a small town so I definitely felt comfortable here and when I walked in I knew this was a good place to be. There was just a feeling about it, you felt cared for,” she said.

But cuts to the Medicaid program could mean cuts to recipients and hospitals like this one. One estimate puts a third of the nation’s rural hospitals in precarious financial shape. Theel admits she hasn’t followed the legislation closely, but she's concerned about this hospital staying open.

“That’s the part that probably worries me, should we lose this that would be devastating,” she said.

Theel is a rare Hillary Clinton voter in this part of the country. She’s concerned about losing what she gets from Medicaid, and apprehensive about the new president.

“I kind of hold my breath every time he opens his mouth and that bothers me. I don’t have a lot of confidence in decisions. Ideas are good, but the way that he goes about it concern me.”

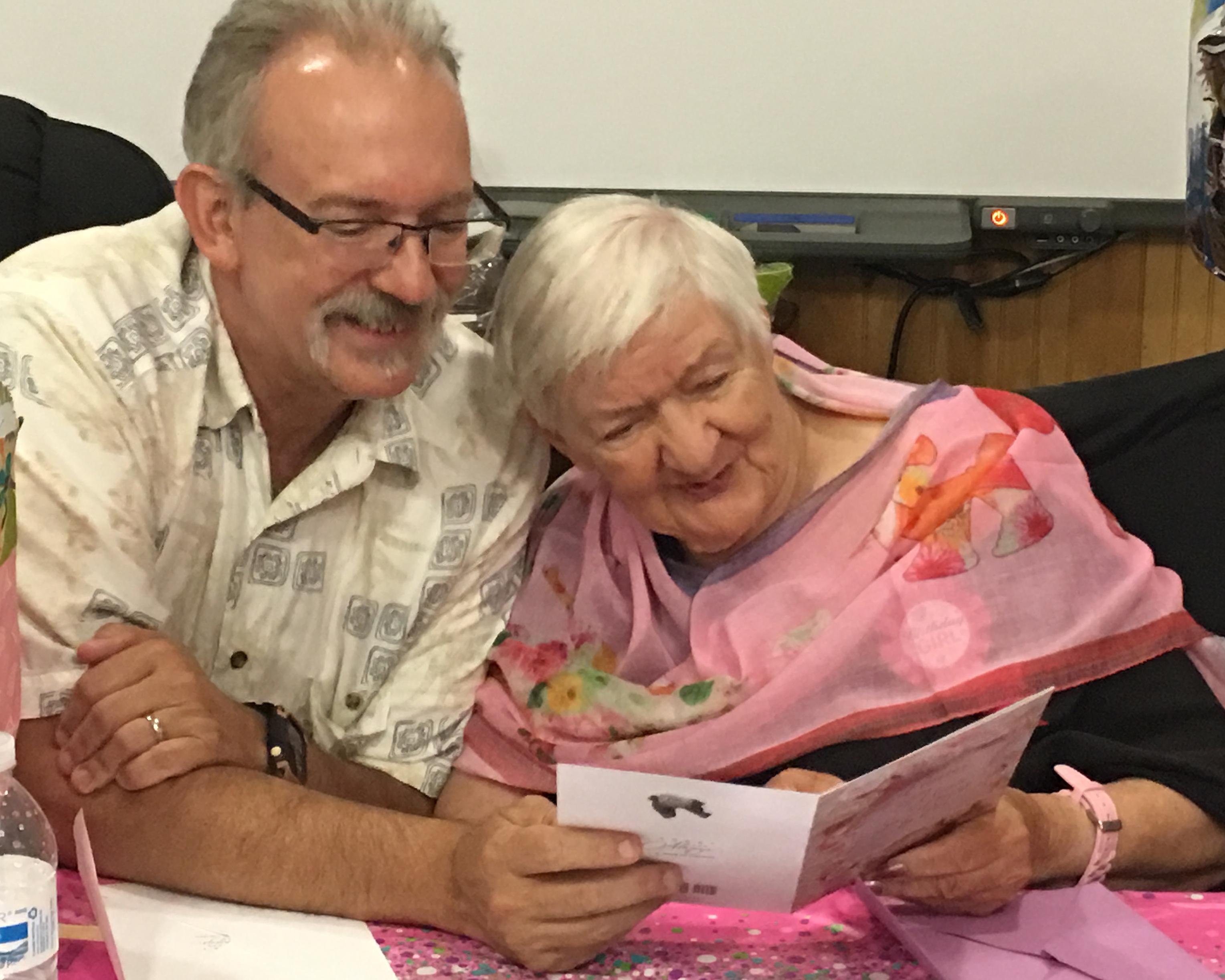

Down the hall, Michael Gaskins is also worried about the future funding of Medicaid, too. He’s the hospital’s IT director and his 90-year-old mother Crystal lives at the hospital. She receives financial help from Medicaid, so he’s watching for changes.

“It is a burden if they make cuts that they're not going to compensate as much, that money has got to come from somewhere and it's going to come from the family,” he said.

Still Gaskins, a Republican, is no fan of Obamacare.

“With the previous administration one of the things that just absolutely floored me was how the cost of healthcare rose. And that was exactly the opposite of what we were promised,” he said.

Colorado saw a historic drop in its uninsured rate under Obamacare. Now a number of major health groups oppose the Republican plan saying they think it could reverse those gains, and even cause health costs to rise more. But Gaskins said he’s ready to give Congress and the new president the benefit of the doubt.

“At this point I have to say that the man was elected president, let's let him do his job. And if he sees a need to take an action, I'm not going to second guess him.”

This is part of a series of stories about people who stand to be most affected, either positively or negatively, by new Trump administration policies. Have a story to tell? Comment below, follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram, or reach us via our Connect page. We’re listening.