When was the last time you opened your mailbox to find a beautifully handwritten letter? Probably not in the last week, or even decade. That might not be a good thing. New research shows that dropping handwriting lessons from schools could be bad for brain development in children. But are children learning to type doing any better?

CPR education reporter Jenny Brundin talks with "Colorado Matters" host Ryan Warner about these topics.

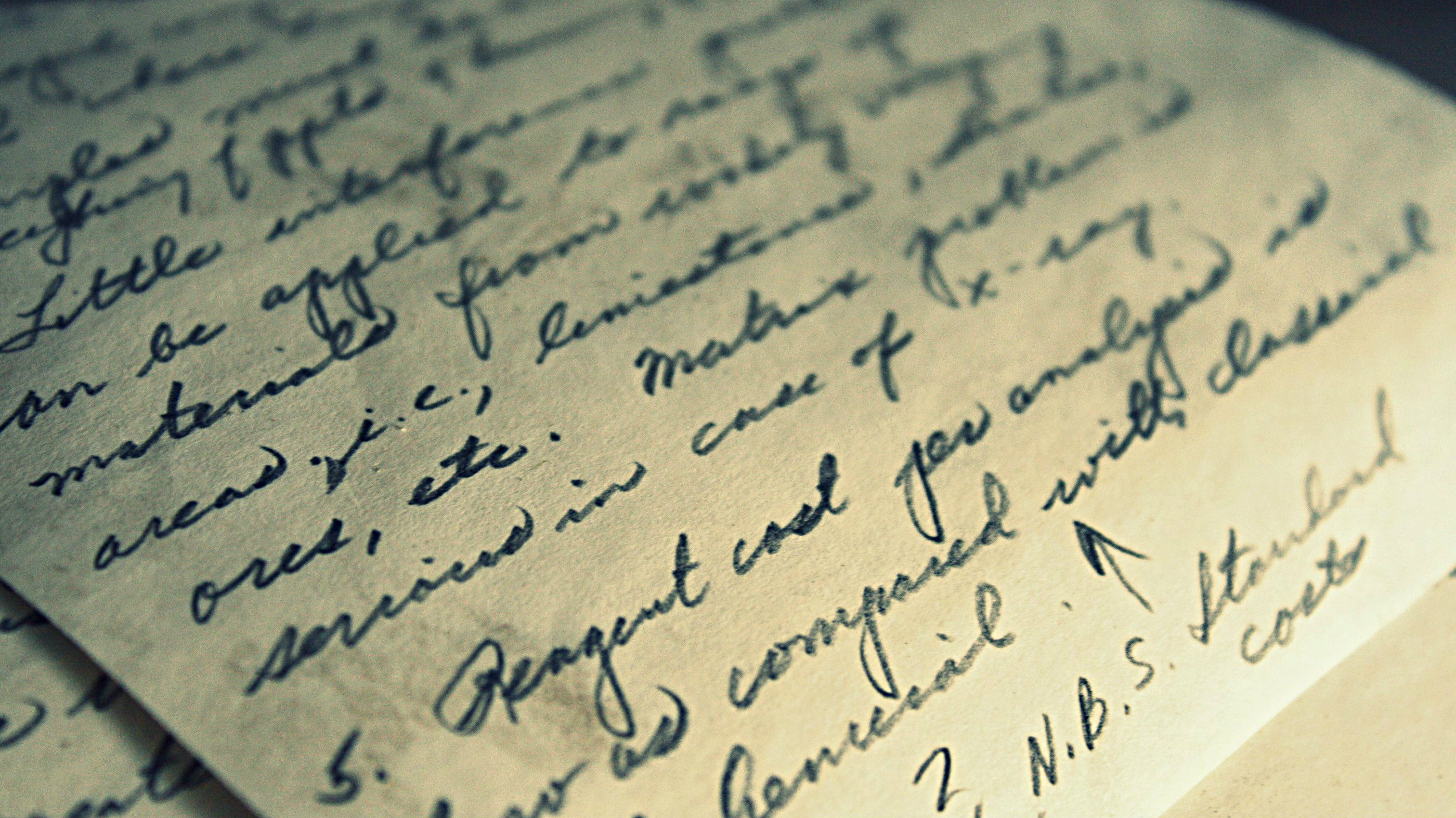

Ryan Warner: Jenny, you want to talk first about -- those graceful loops, rounded angles, and carefully crossed T’s - - that are rapidly disappearing from view. That is, cursive handwriting.

Jenny Brundin: Yes. It’s amazing how much I hear from parents -- even standing in a line at the doctor’s the other day– that they wish their kids knew how to write in cursive.

And so do today’s kids not know how to write in cursive?

As more and more requirements on teachers began piling up -- several years ago the teaching of cursive began being whittled away. Today, I would say few kids know how to write in cursive. The Common Core standards call for teaching legible writing in Kindergarten and first grade but then it switches to keyboarding.

Many people might say, "So what’s wrong with that. Everybody types now anyway."

Well, there’s a report out showing that psychologists and neuroscientists have discovered a link between handwriting and broader educational development. It was written up in The New York Times. It states that children not only learn to read more quickly when they learn to write by hand but they also are better able to generate ideas and retain information.

So how we write matters?

Yes.

What’s happening when we write, exactly?

This is how a psychologist in the Times article explains it: “When we write, a unique neural circuit is automatically activated. There is a core recognition of the gesture in the written word, a sort of recognition by mental simulation in your brain. And it seems that this circuit is contributing in unique ways we didn’t realize. Learning is made easier.”

How did brain scientists start to figure this out?

Well, they took a group of young children who had not yet learned to read or write. They showed them all a letter or shape on an index card. Some were asked to duplicate it free hand; some traced it on a dotted line, and others were asked to type it on a computer. The children were placed in a brain scanner and shown the image again.

What did they find?

They found that how the children duplicated the letter mattered a great deal. For the kids who drew the letter freehand, they had increased activity in three areas of the brain that are activated when adults read and write. But the children who typed or traced the letter or shape showed no such effect. Ryan, scientists think the messiness of when we try to write is key. There’s planning and execution and because the messiness varies, we learn from it, rather than just punching the same key over and over and seeing the same result. That effort each time to draw a better letter “A” engages the brain’s motor pathways.

They found that how the children duplicated the letter mattered a great deal. For the kids who drew the letter freehand, they had increased activity in three areas of the brain that are activated when adults read and write. But the children who typed or traced the letter or shape showed no such effect. Ryan, scientists think the messiness of when we try to write is key. There’s planning and execution and because the messiness varies, we learn from it, rather than just punching the same key over and over and seeing the same result. That effort each time to draw a better letter “A” engages the brain’s motor pathways.

That experiment involved little kids -- what do scientists know about the effect of handwriting on older children?

Another study on children in grades 2 through 5 found that when the children composed text by hand, they not only consistently produced more words more quickly than they did on a keyboard, but expressed more ideas. In older children -- when researchers asked them to come up with ideas for a composition -- the ones who had more advanced handwriting showed greater neural activation in areas connected to working memory, and reading and writing.

What about any difference between printing and cursive writing?

Scientists think these two different ways of writing activate separate brain networks and engage more cognitive resources than would be the case with a single approach.

Jenny, I know my handwriting isn’t great these days. Does handwriting matter anymore for adults?

Well, anybody who writes a lot nowadays types. It’s fast and efficient, but new research suggests it may also diminish our ability to process new information -- i.e. when we hand-write out something -- memory and learning benefit because we are reframing and reflecting.

So let’s talk for a moment about Colorado schools. Do they teach cursive?

Cursive writing is not part of the Colorado academic standards so it’s not an expectation in many districts. But some schools still teach it, a little. In Denver, you might find it in some classrooms – anywhere from third grade to fifth grade. But the focus is primarily is on technology. In Denver, keyboarding is formally taught in 6th grade – but you may find some elementary classrooms integrate keyboarding into tech classes.

Cursive writing is not part of the Colorado academic standards so it’s not an expectation in many districts. But some schools still teach it, a little. In Denver, you might find it in some classrooms – anywhere from third grade to fifth grade. But the focus is primarily is on technology. In Denver, keyboarding is formally taught in 6th grade – but you may find some elementary classrooms integrate keyboarding into tech classes.

So let’s talk about keyboarding. Recently thousands of Colorado students had their first stab at online testing – this was field research for new state tests in English and math. Kids had to drag and drop and type quite a bit. How did that go?

It’ll be a couple of months before we have a deep analysis of how students responded to those tests. Surveys in Colorado found 75% of students preferred taking English tests online, rather than taking written tests. But that dropped to just 50% for math tests. That’s likely because students aren’t as familiar with performing math problems online.

But there’s a hitch -- one that surprised me a little bit, Jenny. Some teachers noticed kids are having trouble with their keyboarding skills.

Yes, testing time was particularly stressful for teachers at one north Denver middle school who noticed some students were having a hard time using the mouse and difficulty typing out answers fluently and using proper capitalization. Especially among some low-income youth -- while they might have superlative skills typing on phones with their thumbs -- they are not familiar with keyboarding and mouse skills.

Aren’t they supposed to learn typing skills in school?

What one teacher observed is -- yes, many kids are supposed to learn typing in technology classes in early grades. But students who have math or reading interventions are often pulled out of electives like technology.

What one teacher observed is -- yes, many kids are supposed to learn typing in technology classes in early grades. But students who have math or reading interventions are often pulled out of electives like technology.

So it’s possible if officials notice a widespread problem, keyboarding will be more heavily emphasized?

Yes. Jill Hawley with the Colorado Department of Education says the analysis will also include how kids performed online versus with paper and pencil. "We’re really in this early stage of exploring and understanding but there is this very heightened attention to making sure is that really every kid can demonstrate their learning and we don’t want technology or skills lack thereof or great skills getting in the way of them being able to show what they know," Hawley said.