Colorado lawmakers this session are planning to give back some of the $1 billion promised to schools with Amendment 23.

Colorado lawmakers this session are planning to give back some of the $1 billion promised to schools with Amendment 23.

Districts know they can't get it all back at once but many say the amount on the table this year doesn't amount to much, particularly in rural Colorado.

Voters passed the school funding guarantee in 2000 but lawmakers found a way around it during the recession using a complex legislative maneuver.

CPR’s education reporter Jenny Brundin talks with Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner about the contentious tussle going on at the State Capitol over how much of the $ 1 billion schools will get back.

The following Q&A captures the discussion:

Ryan Warner: Jenny, break down this billion for us. What does this look like for one district, for instance?

Jenny Brundin: For a district like say, Colorado Springs, that’s about $35 million taken out of classrooms over the past several years. So that’s meant larger class sizes, higher staff turnover, older curriculum, technology that is not up to date, and kids getting less individual support.

Ryan Warner: And this all came at a time when state lawmakers adopted a number of reforms that came with no money.

Jenny Brundin: That’s right. New state standards, new testing and a new teacher evaluation system all went into place over the last few years with no new money. All of those require big investments from districts. So at the same time district budgets were being cut, they were – and are – having to take money out of classrooms in order to meet the requirements of the new laws.

Ryan Warner: So this year superintendents, virtually all 178 of them, rallied and wrote letters to lawmakers saying what exactly?

Jenny Brundin: Yes, they said: "Restore money to our budgets without strings attached." Because every district manages budget shortfalls differently, they said local school boards and superintendents know best where money is needed – not lawmakers. So they didn’t ask for the full billion – they asked for $275 million.

Ryan Warner: So the point being, let the locals decide how to restore cuts, where to restore cuts. How have lawmakers responded to that request?

Jenny Brundin: So right now, House lawmakers have approved a bill that puts $110 million to “buy down” the billion dollar-plus shortfall. And the bill is expected to have its first Senate hearing tomorrow.

Ryan Warner: So $110 million. So you’re looking at about a tenth of that billion dollars. Does that money have strings?

Jenny Brundin: Not as many as the bill’s sponsors wanted at the outset. Though there still are some strings and there will be fights over that (i.e. a provision to create an improved financial transparency system), as well schools will continue to push for more than the $110 million.

Ryan Warner: So how would the “10 percent down payment” affect districts around the state?

Jenny Brundin: Every district is different, of course. But the Colorado School Finance Project surveyed the state’s 178 school districts, and about half responded, so we have some very good ideas about what’s going on for individual districts everywhere. Some districts have passed local tax increases so they’re doing a little better. The larger districts along the Front Range are a little better off – because their enrollment is often increasing – for every student, a district gets on average $6,600.

In a large district like Denver, for example, additional funding in large part will go directly to schools to support higher enrollment and much needed classroom supports including hiring additional teachers, backfilling the reduction in federal Title II funds (preparing and training teachers), and targeted supports for the district’s lowest-performing schools. But I’d like to focus on the smaller, rural districts. If anyone thinks all is well because the recession is over, you just need to pick up the phone and talk to some of Colorado’s rural superintendents. Here’s Michelle Johnstone, superintendent of the Brush district that’s east of Fort Morgan. She’s talking about cuts they’re about to make, even with the hoped-for bump in funding:

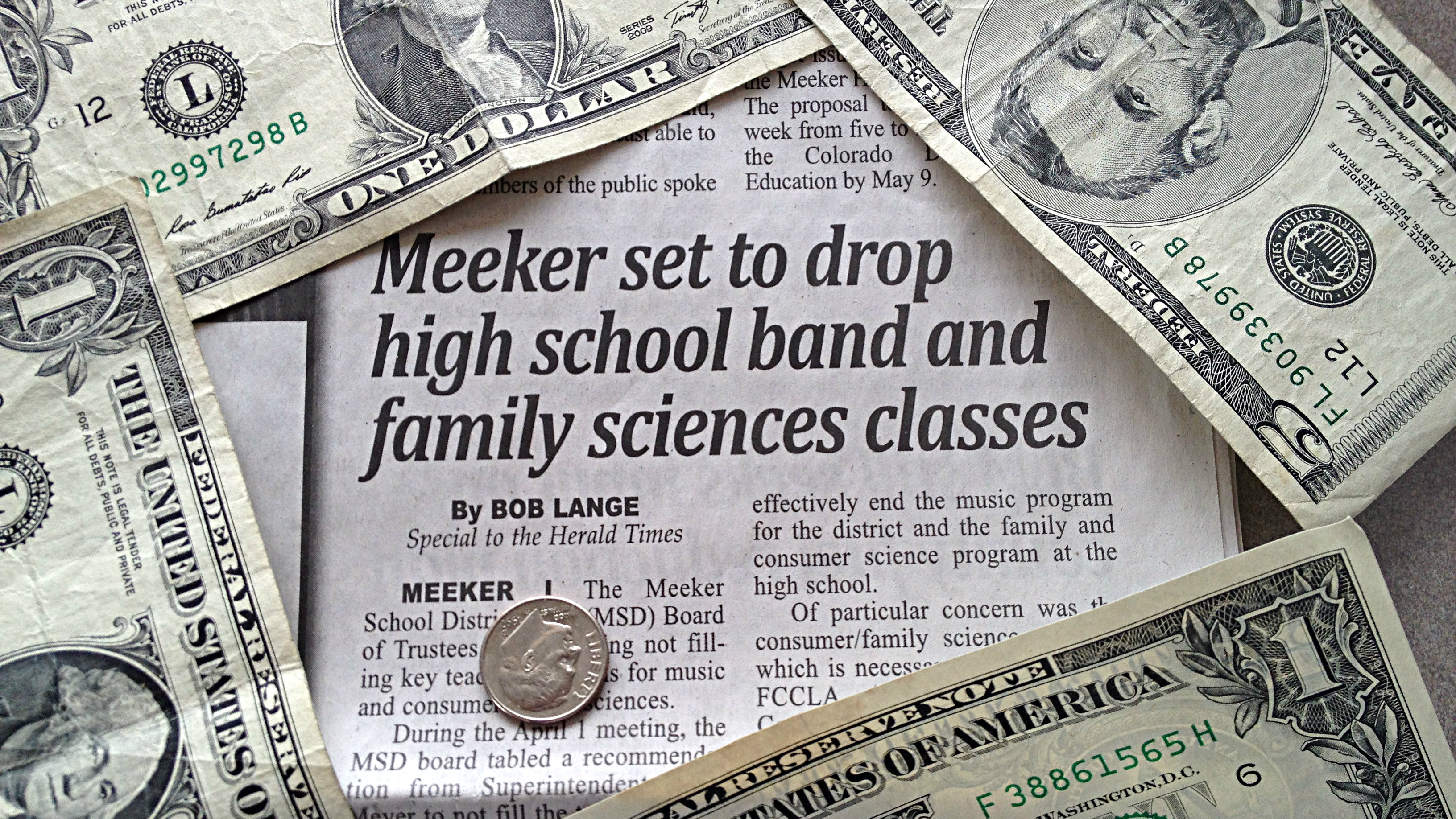

Michelle Johnstone: The programs that are cut are woodshop at the middle school, as well as art as we know it at the elementary levels; we’re eliminating summer school, we’ve eliminated certified dean of students at the high school [and more].

Jenny Brundin: Keep in mind that these are districts that have already been cutting for the past 5 years. Districts like hers do rigorous zero-based budgeting, where they’ve scrapped the budget from previous year and build a new one, only keeping what’s directly tied to helping students improve. So many are down to the bone.

Ryan Warner: Her district is actually growing in terms enrollment but many rural districts are losing students – which is making their budgets even harder to balance.

Jenny Brundin: Yes, Superintendent Jerry Nickell of the Las Animas district east of Pueblo, does a good job of explaining why dropping enrollment hits schools so hard.

Jerry Nickell: If you lose 13 students in entire school district, you can’t cut one teacher because those 13 students are spread out over elementary, middle school, and high school buildings, or let’s close down one classroom because we lost 13 students and save on the utilities, or let’s run one less bus service, or let’s have one less food service person. It doesn’t equate that way.

Jenny Brundin: At the same time just about every superintendent I talked to pointed to increased costs.

Ryan Warner: I’m assuming that’s utility costs, health insurance and retirement – things like that?

Jenny Brundin: Yes. And Nickell’s Las Animas district was really hurt after it lost the state prison – because workers left and school enrollment dropped. For the past 5 years, his revenues have plummeted 40 percent and a third of district staff has been cut. He’s expecting that the little boost back back from the state won’t even cover current expenses. Lots of schools have put off maintenance on roofs, air-conditioning. Here’s Michelle Johnstone from the Brush district again, talking about the aging boilers heating her schools:

Michelle Johnstone: My custodial and maintenance staff has done a phenomenal job of getting 40 years out of something that was meant to last 15. Right now if they blew, I’d have to say, which school are we going to close?

Jenny Brundin: Superintendent Dave Eastin in Wiley, on the eastern plains, says in his drought-stricken region, water is like gold. It costs too much money to maintain the playing field like they want to.

Dave Eastin: We used to have a practice football field that is totally dirt and goat heads [thorns] now, and that has definitely impacted our kids and the number of kids participating. So we are really looking for a solution on that.

Ryan Warner: It seems like the perfect storm because while the funding has gone down, expectations, mandates – have gone up?

Jenny Brundin: Exactly. That is what is frustrating to many of the superintendents I spoke to. There’s immense pressure now for test scores to rise, which will eventually be tied to teacher’s evaluations and whether they keep their jobs. But the cuts are affecting the classroom. Here’s Ron Patera, director of finance for the Elizabeth School District, which borders Douglas and Cherry Creek school districts.

Ron Patera: You can look at some of our test scores over the last couple of years, they’re creeping downwards and so we’re starting to see some of the problems that reduced funding has created.

Jenny Brundin: For next year, Elizabeth has to cut its staff who help and coach teachers in the elementary school. Patera says that feeds into higher teacher turnover. Elizabeth lost a third of its teachers last year. The new mandates from the legislature are also squeezing budgets. In Elizabeth’s $350,000 technology budget, $50,000 that could have gone into things like Mobi – hand-held tablets that students can do work on, or “clickers” to give teachers instant feedback, that money instead went into hardware to prepare for the new state standardized tests. To help balance the budget, Elizabeth is raising athletic fees from $140 to $170 per sport.

Ryan Warner: That’s what families pay?

Jenny Brundin: Yes, that’s right. Another example – one of the laws mandates that kindergarten teachers perform on-going assessments to track what children are able to do – and what they’re not. Here’s Jo Barbie, superintendent of Weld RE-1 district south of Greeley:

Jo Barbie: We’re fearful that they will not have time to do what they need to be doing in the classroom because they’re trying to meet the needs of this assessment – to the point where we actually hired a full-time person to work in all of our kindergarten classrooms this year to pilot this [TS Gold] assessment.

Ryan Warner: So they basically had to hire someone to do all the testing so the kindergarten teachers could continue teaching?

Jenny Brundin: Yes. In Brush, they’ve had to dip into other funds to pay for an assistant principal for the two elementary schools to help with all the new teacher evaluations that are mandated by law. Here’s Michelle Johnstone again:

Michelle Johnstone: That’s about $70,000 our district is spending for somebody to be a licensed principal, to do the teacher evaluations.

Ryan Warner: But of course teacher evaluations are important, right? Worth hiring someone for, potentially.

Jenny Brundin: That’s right. Every school I’ve talked to thinks evaluations are a good idea and show great potential in helping teachers become better. They just say we want the money to do it properly.

Ryan Warner: During the recession, class sizes rose when teachers were cut. Any signs that districts will be able to lower class sizes with the money that the legislature is making available?

Jenny Brundin: Not that I have heard [among smaller districts]. That means hiring more people and districts are still so shaky they’re just trying not to cut more. In Weld RE-4, south of Greeley, some elementary classes have more than 27 students – you want to typically keep those numbers much lower in the primary grades; in high school they have classes of 32 and 34 students. Superintendent Karen Trusler says that makes it difficult for students to practice some of the types of higher level, more critical thinking that’s required by the new tougher Common Core standards.

Karen Trusler: I see more traditional type of instruction going on because of sheer numbers – more lecture format but less time for student dialog. Not always, but in many cases.

Ryan Warner: What about salaries? Will any of the new money districts expect to get to go into salary increases?

Jenny Brundin: Yes. Some districts will try to give teachers and staff a salary increase. Many haven’t had pay raises in 5 to 6 years. This was No. 1 on a lot of superintendents’ lists. They’re losing teachers for a variety of reasons. In Wiley District’s single school, the principal must teach math three hours a day because the district can’t attract a math teacher. Here’s Superintendent Dave Eastin:

Dave Eastin: I went to the job fair yesterday in Pueblo, and I’m sitting between Santa Fe, New Mexico and Tucson, Arizona. Tuscon, Arizona is offering a $3,500 signing bonus and their base salary is $45,000 and ours is $28,700. How do you compete?

Jenny Brundin: Another reason could be competing industries in town. Weld County can’t compete with the oil and gas industry – and they’re losing support staff. Bus drivers with a commercial license, for example, start at $20 an hour in a company connected to the oil and gas industry. Driving a yellow school bus – it’s $14 to 15 an hour. In Custer County – that’s between two stunning mountain ranges in southern Colorado – Superintendent Chris Selle says the scenery and 4-day school week are draws, but with the base salary for teachers below $28,000, it’s a tough sell.

Chris Selle: We had a teaching candidate that we offered a position to and she turned down the position and her primary reason for turning it down was because she worked at Bath and Body Works in the Pueblo Mall and she could make more money doing that than she could teaching in our district.

Jenny Brundin: Selle, like every superintendent I spoke with, says if a billion-plus dollars owed to schools was restored, he could do everything on his list he feels is necessary to help kids learn.

Ryan Warner: So the bill’s up in the Senate tomorrow. Right now there’s $110 million going to “buy down” the negative factor. But education groups will keep pushing for more.

Jenny Brundin: Yes. They point to the growing Education Fund which has hundreds of millions of dollars. There’s a tussle over how much should be kept in that for reserve. Superintendent Jerry Nickell of the Las Animas School District reflects the sentiment of his colleagues when he says more money is needed now.

Jerry Nickell: $110 million is certainly a step in the right direction. But it’s not a large enough step. We’ve lost $1.2 billion dollars over the last 5 years. $110 million is about 10 percent of that. Well, if that’s the direction the legislature is going, it’ll be 9 more years before we will be funded where we were five years ago. And it’s much too long. For lack of a better expression – it’s too little, too late.

Ryan Warner: Well, Jenny, you’ll keep following the story. Thank you for being with us.