National trends indicate that by 2020 the percentage of teachers of color will shrink to an all-time low of 5 percent of the total teacher force.

But nearly half of all public school students across the nation will be students of color and minority teachers in Colorado make up only 12 percent of the population.

Many believe that recruiting more teachers of color is one way to help address the wide gulf in test scores between minorities and their white peers.

Research on whether kids perform better when a teacher looks like them is limited but a 2011 study of community college students found the black dropout rate dropped six percentage points for blacks who had a black instructor.

Having a teacher of color can be a powerful example for all students, helping to dispel myths and stereotypes, especially for minority students.

‘I won’t forget that’

DeMarcio Slaughter still remembers a single day more than 30 years ago when a black substitute teacher walked into his 2nd-grade classroom in Colorado Springs.

“I didn’t know teachers came in black, at that stage, at my age,” Slaughter recalls.

“I remember I was having difficulty with the abacus and she helped me with that,” Slaughter says. “It was really interesting to be in the room with this woman. And I remember that feeling of having someone who was like me. I won’t forget that. I don’t know why. But I won’t forget that.”

Slaughter eventually got a scholarship to become a teacher but other opportunities came along and he ended up in the hospitality industry.

Tough to recruit

It’s tough to recruit teachers of color to a mountain state like Colorado where the majority of the population is white.

Denver Public Schools works to recruit teachers by targeting colleges, faith groups and community organizations where blacks and Latinos congregate.

The district runs a residency program to train college graduates and mid-career professionals to be teachers.

The number of black teachers in DPS has dropped to 4 percent while black children make up 14 percent of the student body.

The gap is even larger for Latinos: 58 percent of district students are Latino while only 17 percent of teachers are.

It wasn’t always this way

With segregated schools, thousands of black educators entered the profession because it was one of the few jobs black women could do.

“They went into teaching for a reason of community uplift, of race uplift, and so it was a time when we felt like we had to improve the race and improve the communities for the future,” William Patterson University Professor Djanna Hill says.

As more career options became available, teaching became a less popular choice, especially when students of color faced the challenge of paying back college loans. It’s a lot easier to pay those loans as an engineer than a teacher. And influential adults often steer students of color away from teaching.

“Many times guidance counselors are pushing them to do things that are much more lucrative," Audra Watson, with the Woodrow Wilson National Teaching Fellowship Foundation, says. “And their parents are saying to them: ‘You could do anything, why would you want to teach?’"

Role model

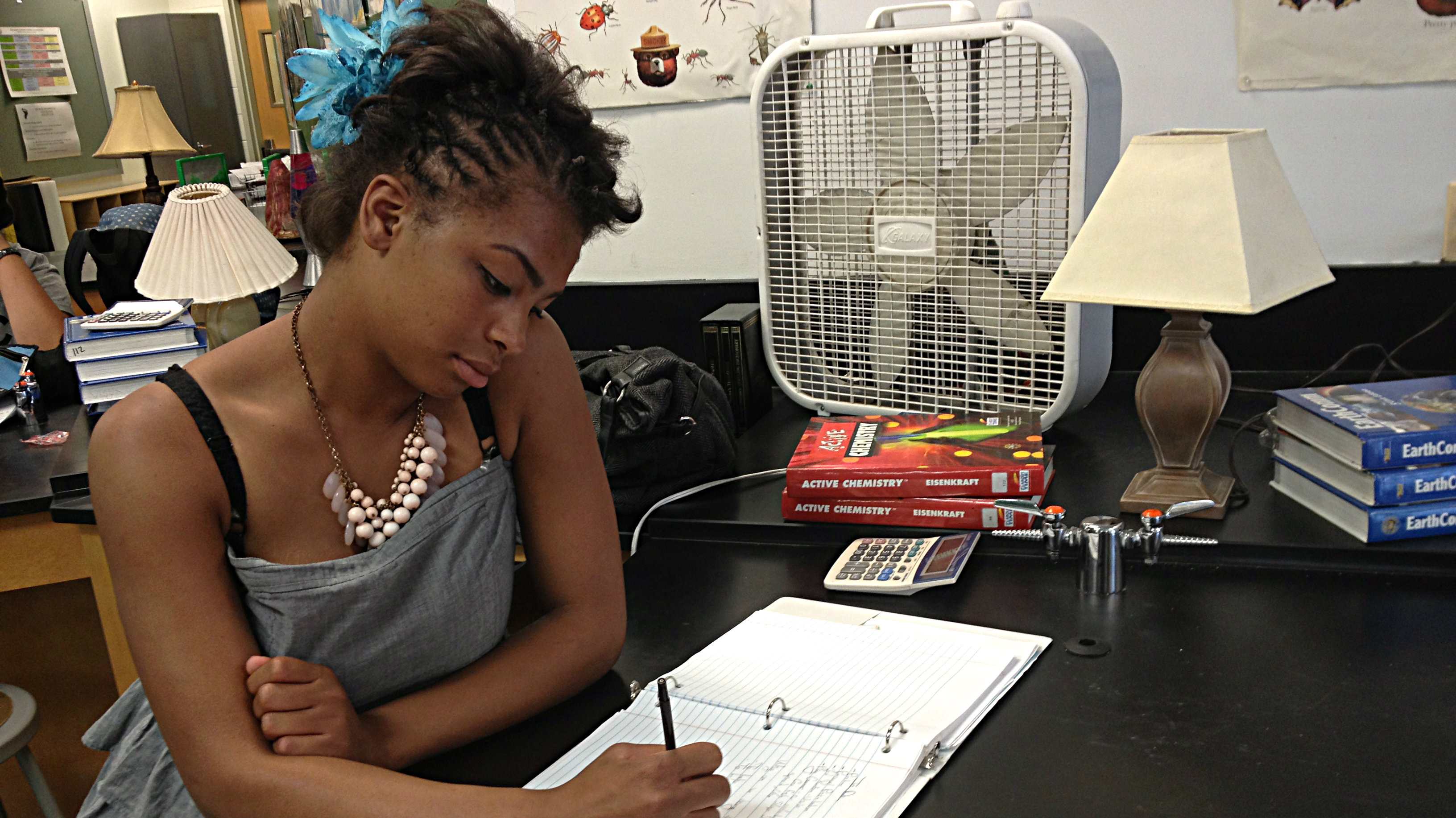

Retha Jenkins wanted to teacher and being a role model is partly what propelled her into teaching.

Jenkins is African American and comes from a similar background as her students.

“I want students to see someone who looks like them,” Jenkins says. “This is a brown lady who has a degree in microbiology, she also has a family, she’s a teacher, she’s a positive, she cares that I succeed and that I learn.”

Jenkins says that it’s also important for students of color to see a reflection of themselves in their teachers.

Jenkins tells her students about troubles she faced in school, how the mean girls wanted to beat her up and how she learned to keep to herself to get through.

Jenkins says one particular story helps students face their own struggles: The day she took a seat in the front row of a physics class for engineers and scientists at a university in Colorado.

“The professor comes down from the podium and says: ‘Do you realize this is the physics classes for engineers and scientists?’” Jenkins says. “Yes. Yes sir, I’m here for that.”

The identity of the teacher also sends a strong message about what young students can be when they grow up. Shaffinity Owens, a recent graduate from Denver’s Manual High, finds the idea of teaching inspiring.

“And when I see a teacher of color, it’s just like, I know I can do it because somebody else of my color is doing it and they’re very good at what they do,” Owens says.

Grow your own teachers

An innovative program run by CU Denver is trying to cultivate teachers of color by starting in high school.

George Washington High School is one of two Denver high schools that have the University of Colorado Denver’s Pathways2Teaching program.

The program is for high school students of color to explore teaching as a possible career by visiting college campuses, tutor first graders at a nearby school and learn about how inequities show up in schools.

The students talk with teacher Chantel Maybach about the factors that contribute to the achievement gap, like poverty, inadequate funding for schools and low expectations from some teachers.

And several students describe how they once withdrew and didn’t do the best work possible because other students made fun of them for trying hard.

“I tried dumbing down a bit around other people, not being me, because I felt like I’m going to get beat up if I do, beat up behind the slide like that other kid,” Ildefonso Bravo-Torres says. “I want to show these kids [that he will tutor] that no matter what other people say, you know you’re going to going to end up being a good student, going on and doing greater things if you just stick with who you are and what you know to do.”

The first group of the Pathways2Teaching program graduated high school in 2011. Many are unable to afford college full-time so it will likely be a while before the program sees its first teachers ready to work in Colorado classrooms.