When you hear stories about poverty, they’re usually not focused on how a person's brain deals with stress. But there's growing scientific evidence that experiences like homelessness or living in a dangerous neighborhood actually changes the brains of young children. Without intervention, these experiences can have profound consequences later in life.

- May 19: Poverty changes a mother's brain and her baby's as well

- Part of Growing Up Poor: Childhood Poverty In Colorado

Katrina Haselgren knows about that personally. Her life was poverty, strife and chaos 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

"I would lash out and I would beg for help. I needed someone to advocate for me. I didn’t think I had a voice at age 13, 12," she says. "I was always told to be quiet. Don’t say nothing."

Her mom didn't pay her much attention; that was reserved for Haselgren's unpredictable stepdad, and a situation in which she says "my mom always showed love to a man that always beat her."

As a result, she never felt safe. She never felt the love of her family even though she was always trying to defend her mom, once even calling the police after her mom was beaten. Finally, at 14, Haselgren couldn’t take it anymore and ran away from her Denver home, already damaged.

"Growing up I had these relationships that were horrible, with men that would put their hands on me or that would treat me so bad,” she says. And she thought, "That’s what love is."

She cleaned dog kennels at 15 to pay for all her school supplies. She saw her best friend overdose and die in front of her.

"That ...” she says and then pauses. “That was a very big eye-opener. And I said I had to get my life together."

But where to start? So much damage had already been done.

'The canary in the coal mine'

Researchers are building a body of evidence that shows how adverse childhood experiences can have a profound impact on a person’s health, emotional development, and their ability to focus and learn in school. It's the kind of stress that might have affected Haselgren, who is now 29 years old, as she sat in a classroom at school. Or later in life, when she became a mother to four boys.

Researchers say there's such a thing as good stress for children. This happens when there are supportive adults around to help children face their challenges, and learn to overcome them.

Stress can also be life-saving, says Nadine Harris Burke, a San Francisco-based pediatrician and a leading researcher on this topic at the Center for Youth Wellness. Imagine you’re walking in a forest and you see a bear. “In that moment, your brain's hypothalamus sends a signal to your pituitary gland, which sends a signal to your adrenal gland to release stress hormones, adrenalin and cortisol,” she says. You’re going to turn off the thinking part of your brain, the pre-frontal cortex, and instead pay attention to the parts of the brain activated by fear.

You’re going to fight that bear.

"That’s great if you’re in the forest," Harris Burke says. "But it’s a real problem when you’re a six-year-old and you’re sitting in your first grade classroom and the kid next to you hits you, right? Kids who have been exposed to high doses of adversity? The canary in the coal mine often times is behavior and learning."

When stress becomes toxic

If that threat response is activated over and over, it becomes toxic: "The stressors just keep coming and coming,” says Sarah Watamura, a researcher at the University of Denver who studies stress and health in young children and ways to buffer stress among families experiencing poverty.

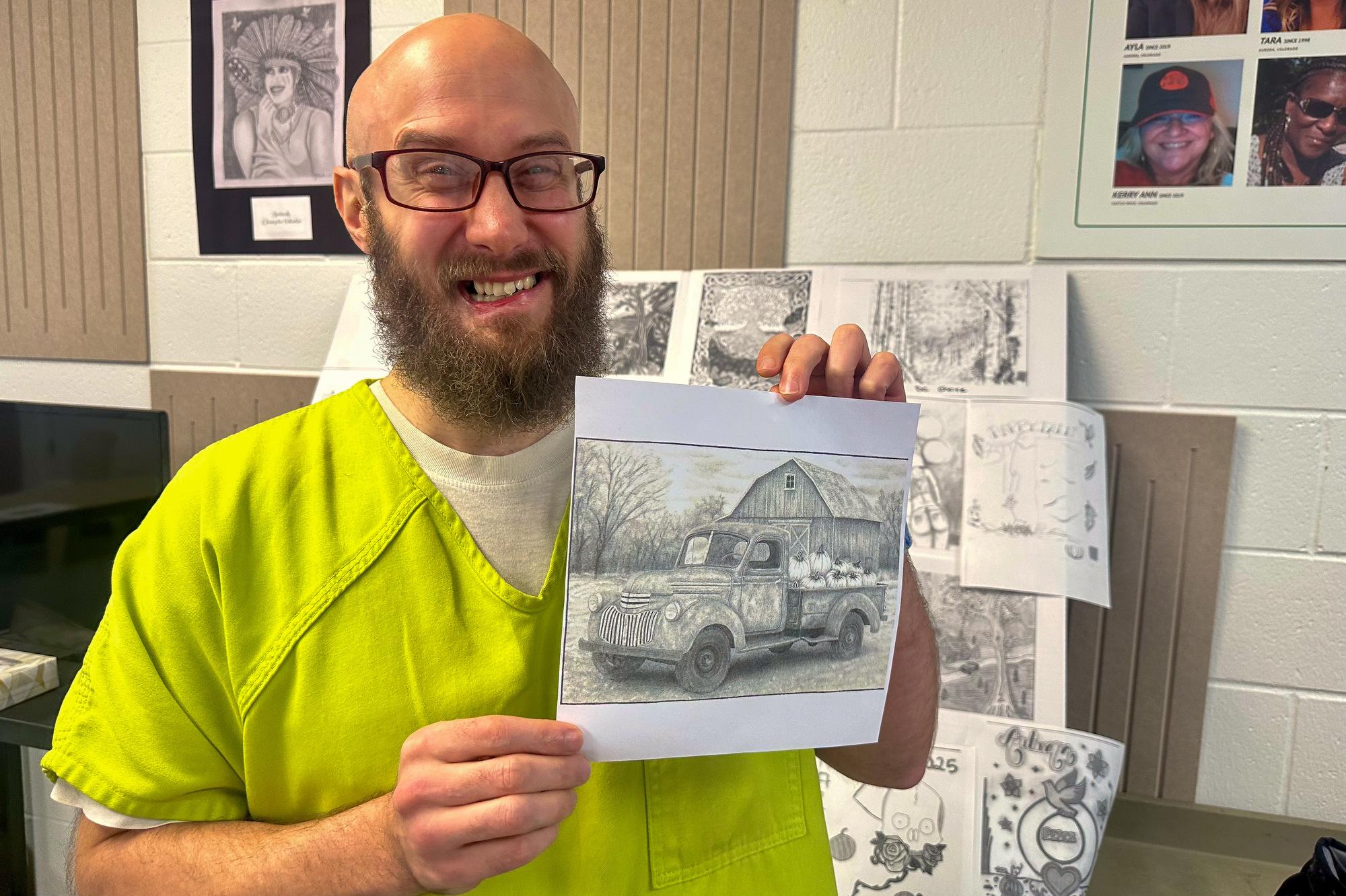

Elijah Jones, 10, tests a stethoscope on his brother, Dimitri, 11, in the back of an ambulance at a community event hosted by the Clayton Early Learning in Denver on Saturday, May 16, 2015. Both Elijah and Dimitri are children of Katrina Haselgren.

“The child is trying to handle those stresses without the support of the adults in their environment, because their parents are not well, because they’re unavailable," Watamura says. "They’re working really long hours, so they’re just not home. So they’re trying to handle all these stressors on their own and their (a child's) brain and body is not prepared to do that."

Researchers call these kinds of things adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. Experiences include things like divorce, abuse, neglect, a caregiver who abuses drugs or alcohol, homelessness, or seeing domestic violence, among other factors. In Colorado, children under 18, one in five has been exposed to at least two ACES. For poor children, that rises to one in three.

Harris Burke says the more ACES you have, the higher your risk for health problems and behavior and learning problems like memory and attention.

What might this mean for the thousands of kids sitting in classrooms who carry those ACES with them?

In Harris Burke’s study of hundreds of families in one low-income California neighborhood, of her patients who had an ACE score of zero, only 3 percent had learning and behavior problems.

“For me, I think that was really, really, really promising,” she says. “It suggests that our kids are not inherently broken, right, but that they are manifesting symptoms of an exposure to a toxin, which is adversity."

The other numbers are staggering: For kids who had an ACE score of four or more, 51 percent of them had learning and behavior problems in school.

"What happens when an individual faces a lot of stressful experiences,” says DU researcher Watamura, “is they hone in on being vigilant to threat, and when you’re very vigilant to threat and, you’re just monitoring your environment all the time for things that might happen that might hurt you or harm you, it’s very hard then to pay attention to things with long-term interest or long-term outcomes."

Outcomes like doing well in school, or building a healthy, happy future. You're focused on survival.

'Yelling and screaming'

When you think about the ACE score of someone like Coloradan Katrina Haselgren, it’s probably off the charts. She says her violent and chaotic childhood affected her decision-making, her ability to plan ahead, and her parenting.

Haselgren became pregnant by a much older man. Eventually, she, like her mother, was battered -- and Haselgren and her sons became homeless. But she was determined to make her relationships with her kids better than hers were with her parents. Yet, all she knew is how she was raised, so she began raising her boys the same way.

"It [was] just crazy,” says Dimitri Haselgren, her oldest son, who is 11 years old. “She kept on yelling and screaming. There wasn’t any understanding and it didn’t make us that calm and safe to talk."

Haselgren would think of herself as the boss, who had to tell her children what they couldn’t do. She remembers now that it was just like how her parents treated her.

“There was a lot of chaos. So it was like I wasn’t allowed here. I wasn’t allowed there. I was never told what I could do,” she recalls. “It would be like, ‘you’re not allowed to go in the kitchen, you’re not allowed to go here.’ I mean all the rules that I had growing up, I was doing it to them, and it wasn’t fun. And they weren’t learning anything. They were like a robot doing what I told them and doing [it] by memory.”

Researchers like Sarah Watamura take great care not to stereotype or stigmatize families in poverty. She says that, just because a family lives in poverty or lives in stress, that does not mean the moms and dads are poor parents. Instead, they need support. When you live in chaotic situations, with low resources, it becomes difficult to take the extra time to get on the floor with your baby, and do those key interactions to help them build their brain.

"There just isn’t the time, there isn’t the energy, families are exhausted,” Watamura says.

But at the same time, because young children’s brains are so malleable, there are simple interventions that can help buffer the adversity a child experiences and that can help parents or caregivers develop a child’s brain in a more healthy manner.

Katrina Haselgren realized she was part of the stress her kids faced and had to learn how she could interact with them in a new way.

"When there’s one door that closes, another door opens -- you just have to search for it,” she says.

Tomorrow we'll learn about how Halsegren changed her parenting style to help give her children the opportunities she never had.