Ecno ynam sraey oga a relddif emac ot eht egalliv. Eh doots ni eht egalliv erauqs litnu eht elpoep emac ot netsil dna ot ecnad. A ylloj rehctu decnad htiw eht diamklim.

That was the sentence in front of me and I didn’t know what it said. I was always a pretty good student. But here I find myself, decades later, sitting around a table with other “students” -- actually, teachers from metro Denver schools -- with an assignment to translate it.

“I’m going to have each of you read either a sentence or part of a sentence out loud,” says our ‘teacher,’ sounding very much like a real elementary school teacher and suddenly making me nervous.

We’re going to read a simple story at this simulation session designed to let teachers know what it feels like to be a student who can’t read.

Easy enough. But when I look at the page, the letters are a jumble and I don’t know the sounds connected to the characters. Much the same thing happens to people with dyslexia, the most common neurobiological disorder that affects pronouncing written words, spelling and reading.

Suddenly, it’s my turn to read.

“Do you…” I start.

“Do you…” I repeat. I’m stuck.

“Like,” the teacher says.

“Like,” I repeat.

“Do you like …….being……?” I say tentatively.

I’m stuck again. I feel dumb. A couple of teachers in my group seemed to catch on to some code they’d figured out that helped them translate the written chaos. But most of us can’t.

In The Shoes Of Someone With Dyslexia

“The purpose of our dyslexia simulation is to put people in the shoes of someone with dyslexia,” says Terrie Noland, a national director with Learning Ally, a national nonprofit organization that supports students who read and learn differently. There are many different reasons including dyslexia, blindness and other disabilities.

“The actual experience takes you through trying to decode something that’s not familiar to you...and say, ‘OK, try to decipher what that is.”

Learning Ally doesn’t train teachers how to teach dyslexic children. But since Colorado doesn’t have screening for dyslexia in public schools, it helps teachers uncover dyslexia’s warning signs at each grade level.

Other simulation sessions showcase strategies to learn the reading and spelling rules that dyslexic students need to succeed, what accommodations can be made, and how to integrate assistive technology into the classroom. Learning Ally also offers academic materials in an audiobook library of 82,000 materials -- literature, math and science texts read out loud. Students can access text at the same time as the audio, which allows them to keep pace with their peers. Parents and teachers can also monitor progress online.

Noland says audiobooks help bring kids up to grade level for content.

One study showed that students using Learning Ally’s audio textbooks improved their reading in general, and made gains in word recognition, reading rate and comprehension. The program is offered in 80 percent of Denver's public schools and will soon be offered in all of Denver’s Catholic schools and is starting in 11 Jefferson County schools.

Feeling Helpless

Back at the simulation, our teacher says she can see some of us didn’t do our homework from last night. It feels demoralizing. Later she tells us to read faster or we’re going to miss recess. We feel worse when she says that.

This is also the purpose of the simulation.

“That emotional side starts to come in where frustration creeps in and where self-doubt comes in and how others are starting to look at me in the class,” says Noland. “[The simulation] provides that sense of empathy in order to understand what it’s like when students are accessing text.”

As my group struggles to read, we notice that our comprehension plummets. Even after just 45 minutes of the simulation, we are all frustrated. Some even get a little snarky and defiant. And that’s what happens in real classrooms, the teachers say, describing what they’ve seen: acting out, shutting down, avoidance, being angry, and saying "who cares?"

The simulation instructor asks the teachers how they feel after the exercise.

“Is everyone ready to go for another class, another test?” she asks. Everyone groans.

“I was done after two chances,” says one teacher. “I was like ‘oh what’s the point?' ” says another. “I’m not going to be able to do it. I felt hopeless.”

The instructor reminds the group that for a dyslexic child or a student with a learning disability, the school day can present enough opportunities to fail, that after three tries, emotionally, they’re done.

“That emotional strength, do you feel, it’s kind of disappeared,” the instructor says.

Changing Methods

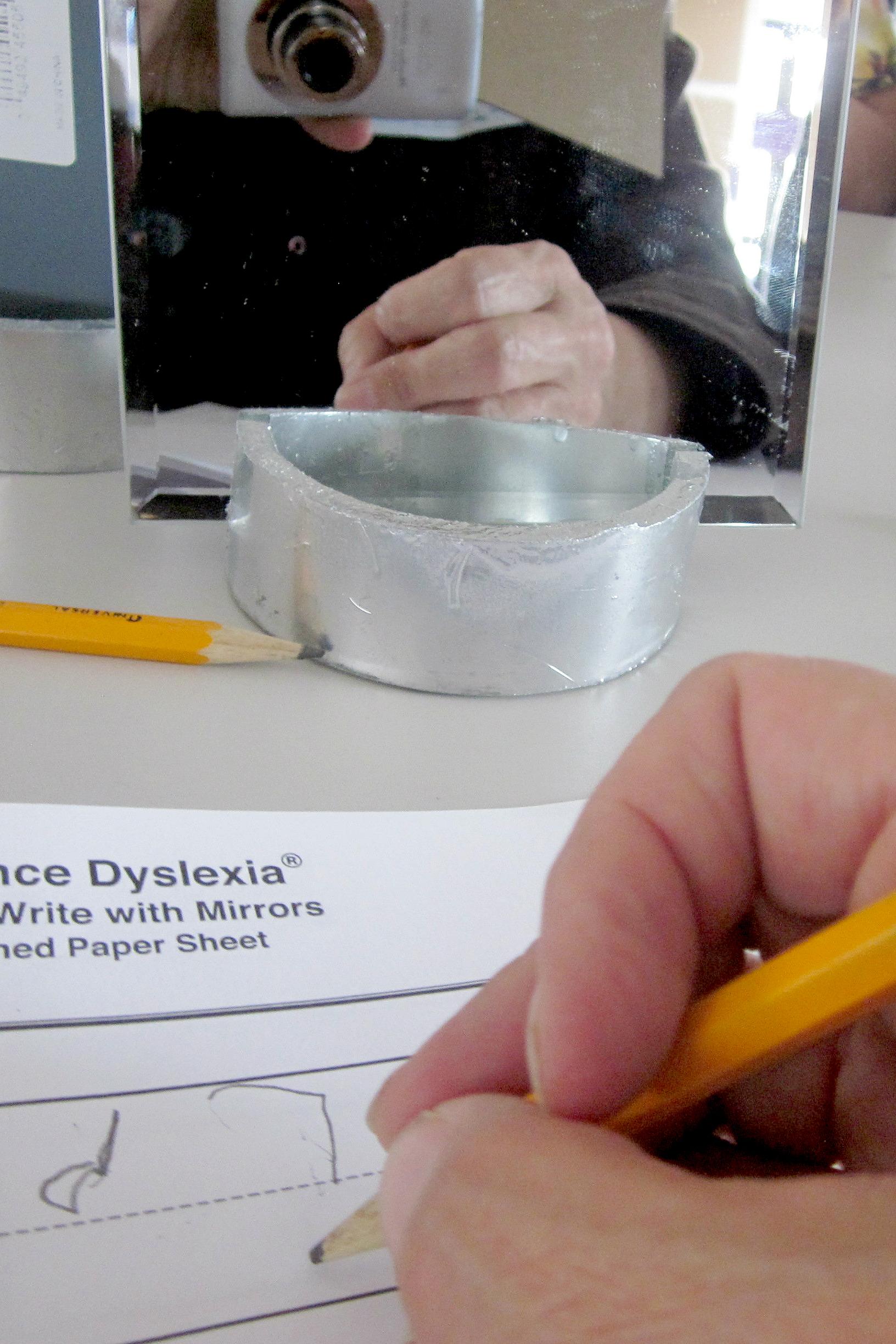

During another exercise, we have to write looking not at our paper, but at our hand in

a mirror. Special education teacher Jacquie Nervick says for the first time, she really feels the exhaustion her students do and realizes they need more breaks. She’d like to see all regular classroom teachers do the exercise. Special education teachers often talk to classroom teachers about giving certain kids less or no homework or shorter assignments.

“And they really don’t understand why that would be important and they don’t understand the behavior that comes from being exhausted,” says Nervick, adding that more training about specific subsets of students is a lot to ask of teachers who already have very full plates.

The teachers hear themselves in some of the lines the simulation instructor uses to motivate.

“ ‘Do your best,’ ‘make good learning choices,’ ‘follow along,’ ‘use your finger,’ those things that we say that we think are encouraging can really be discouraging,” says Barb DelCupp, who teaches at the School of Education at Colorado Christian University and who is a 30-year-teaching veteran. Or another common refrain, "no cheating, eyes on your paper."

At the dyslexia simulation, these teachers find out that is how many students compensate for a deficiency they have.

“We as educators are not always as empathetic as we should be towards kids who struggle," DelCupp says. "We often feel the pressures that the school environment and the school culture place on teachers, therefore we place it on the children to perform at a certain level which makes it extremely difficult.”

Many of the teachers here tell stories of being unprepared to teach dyslexic children.

Reading interventionist Teresa Aye says some of the skills she uses with her students have come through what she’s learned working with her daughter who is dyslexic. Aye says without training, teachers can’t help dyslexic children move forward.

“Nail on the head, that’s what happens. We stumble through our careers,” she says.

At this simulation though - teachers are learning teaching strategies - and skills. Things as simple as not interrupting students when they’re focused on a task, or asking a student who is dyslexic ahead of time whether they want to read out loud.

We are also leaving class today finally understanding a little bit, how it feels to be a child struggling in a classroom.