While the thought of nuclear war has largely been relegated to history lessons and old YouTube videos, recent rhetoric between the leaders of North Korea and the United States has raised the specter again. To be sure, the threat of a detonation in Denver remains very, very small.

Yet, there are still safe places to go inside many of the city’s public buildings in the event of doomsday.

They’re the old civil defense fallout shelters. Eagle-eyed Denverites can still spot some of their marker signs around town, just look for the yellow and black sign with three triangles.

When we reached out to the Denver Office of Emergency Management to ask about the shelters, they were top of mind for them. The mayor and his appointed staff had recently ran a “routine exercise” which touched on current events, planning for the relocation of U.S. citizens if war erupted in the Pacific.

“They want to evacuate U.S. citizens in South Korea, Guam, Japan, and Hawaii,” if it came to an armed conflict, says Denver OEM executive manager Ryan Broughton. They’d be brought to Denver, and other cities with big international airports, to “distribute them back across the country to their homes or their friends or to another military base if they came from a military base,” he says.

At the height of the Cold War, Denver and other cities across the nation declared buildings safe in the event of a nuclear detonation. The historic Denver Fire Station Number One is such a building. You can still see the rectangle stain where the sign was affixed on the left side of the building. It’s just one of a thousand shelters the Denver Office of Emergency Management says existed between 1962 and 1974.

“If [the public building has] a fallout shelter sign on the exterior, it does mean that as of the 70s, it was rated to provide better protection than being outside, or inside a wooden framed house,” Broughton says.

Other shelters included Denver’s City and County Building, the state Capitol, the Downtown Denver YMCA on 16th Avenue, as well as numerous schools, fire and police stations. OEM noted that there are private buildings on the list too.

They’ve long been decommissioned, but Broughton says the shelters used to be fully stocked with “water, food, medical supplies.” At one time, Denver’s City and County building had 99 water drums in the main basement and another 112 barrels in the tunnels underneath the building.

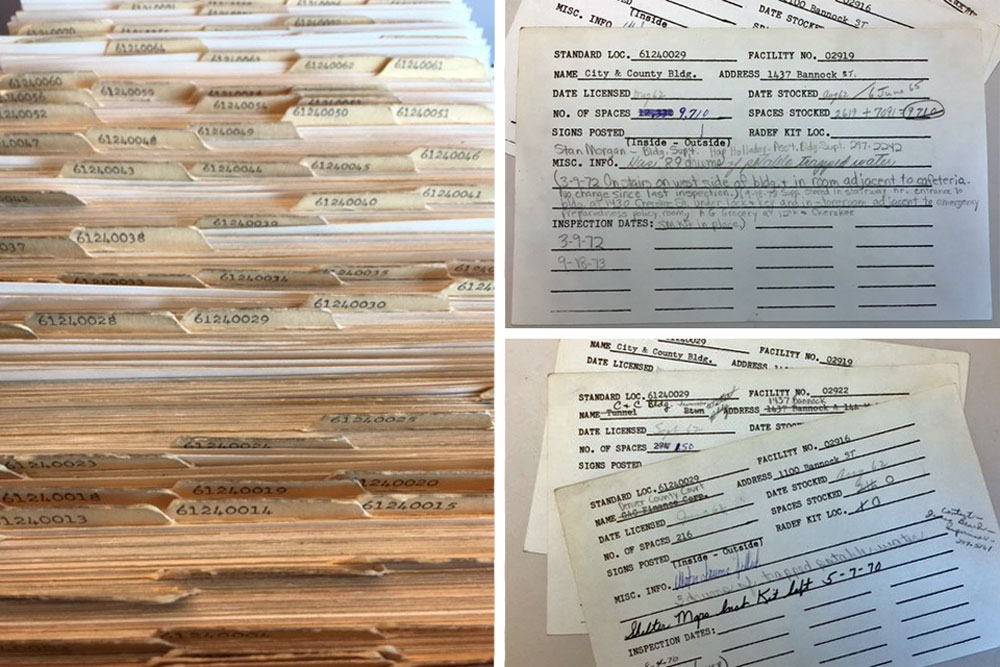

While the exact locations of the Denver shelters still exist, they’re not exactly cataloged in a very 21st century manner. The full inventory is found on scores of yellowing paper index cards at the Denver Office of Emergency Management. Not exactly helpful, or quick, if the missiles were raining down.

The chances of severe weather, a power outage, or even a train derailment happening in Denver are much greater, but if a nuclear detonation were to occur, Broughton says the shelters would still provide adequate protection from any radioactive fallout.

Of course, you’d have to bring your own emergency supplies.

“Bring your own water, your own food, your own medicine so you can stay there until it’s declared safe to leave,” Broughton says — which, by the way, is a minimum of 48 hours.

P.S. The Office of Emergency Management always asks that everyone prepare for all hazards. Make a plan, build a kit, and stay informed. As Broughton points out, it’ll make you “better prepared, whether it’s a nuke or a tornado.”