A couple of dozen districts piloted the system last year. Perhaps the easiest way to explain how it works (instead of reading the 146-page user guide), is to imagine a pie. The evaluation pie. How well you score on each slice of the pie feeds into your overall score. Half of that pie is how your students do on tests. The other half, roughly, is how observers rate your skills in the classroom, looking at things like how you deal with students who are confused or how you monitor progress. Teachers say it’s a far cry from how they used to be evaluated.

“Before ... we had what we called ‘dog and pony’ shows,” said Emily Yenny, who taught fifth grade in Loveland last year. “We would know when our principal was coming in, and it would be a scheduled time, and we had a conference before and after.”

Last year, everything changed. Her principal was checking out her classroom sometimes weekly. That’s because her school was piloting the teacher evaluation system.

“It made me a better teacher, and I know that sounds silly, but it did because I always wanted to make sure that the work I was doing with kids was the very best work and that it didn’t just happen in this ‘dog and pony’ time,” Yenny said.

Teachers say there was lots of anxiety at the beginning. It’s like taking your job and breaking down every single thing you do into the smallest categories, analyzing how you do them, and being graded on all of them. There are standards like how well teachers know content and how they help kids learn. Teachers wondered what evidence they could show to prove they’ve met the standard.

High school math teacher Kristina Smith, also from Loveland, said at the outset, her assistant principal put her at ease by telling her not to worry about everything and instead to focus on one element of one standard.

Smith was supposed to bring more literacy into math, so she had kids write down how they got an answer and why they chose a particular method to solve a problem.

“My kids were writing,” she said, “because I was pushed to have my kids write in my math class.”

Student feedback on teachers will also be scored. For some teachers, that may conjure up nightmares of hormonally-charged, revenge-prone teenagers weighing in on their futures. But Smith said she was excited.

"I got the results back, and I could see exactly, ‘oh, my kids feel like I don’t give them enough say in what they learn,'" she said, "so I need to do something in my classroom to have them feel like they have an input in their education."

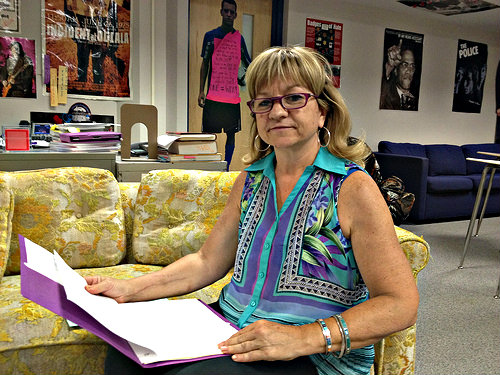

Most of Colorado’s 50,000 teachers will get their initial taste of the new law this year. Some are jumping in feet first. Wheat Ridge High social studies teacher Stephanie Rossi created a simplified guide for teachers in her department that she calls the “educator effectiveness bible.” She hopes it helps. Rossi’s been teaching for 33 years, but the new system is all new.

Teachers like Rossi will be evaluated on a four-point scale, from highly effective to ineffective. This year, those ratings don’t count. It’s a practice year. Next year, they will. New teachers will have to get three years of effective ratings to gain tenure, and then they could lose tenure if they get two years of poor ratings.

Rossi says teachers are not ready for the change because they’re nervous about how things like student growth will be measured. But she says teachers are ready to experiment with the evaluation system, and that so far the change has inspired deep conversations about things like how to get kids to analyze a topic more deeply.

She said she's been in discussions where questions have come up like, “what does analysis look like, what does it sound like, and how do you measure that?”

She told the teachers in her social studies department that they are all going to have to be comfortable with not knowing everything.

“We don’t have all the answers to this yet,” she said. “That’s OK.”

She told them the “hold harmless” year is the time to figure out what worked, what didn’t, and what they might do differently the next time.

“And so I said, ‘don’t push the panic button,’” Rossi said. “'Don’t push the panic button.'”

Rossi does have some concerns. Districts aren’t getting any extra money to implement the new system, so her biggest worry is “that everybody that’s involved in this will be provided training to do it right and given the time to do it so it’s to improve the art of teaching, so that it doesn’t become this heavy task that people are lugging around all the time and we lose focus on what we have to do with student learning and student growth,” she said.” I don’t want it to become so monstrous. That scares me a bit because it’s monstrous now."

There’s reason for optimism though. Back in Loveland, teacher Michelle Logan says anxiety was high at the outset of her school’s pilot year, but teachers' nerves were calmed by the end.

“Their feedback was, ‘it wasn’t as bad as we thought,’” she said.

[Photo: CPR/JBrundin]