The company works not only with school children, but with medical students, equine enthusiasts, and professional dancers.

On a weekend morning in the sunny, spacious studios of the Formative Haptic Center in Denver, anatomy teachers are building their own knowledge to bring back to their students.

Throughout the day, they learn interesting facts about relatively obscure body parts, like the left hepatic flexture of the colon, the Ampulla of Vater, and the von Ebners glands. They learn that the little hole going from your soft palette to your nose helps relieve pressure so you don’t blow your head off when you sneeze. They also find out that the liver has 1,500 functions.

“It has an enormous number of functions, that’s why you can’t live without it. You’d have to have a liver transplant,” says instructor Teri Fleming,a former high school anatomy teacher.

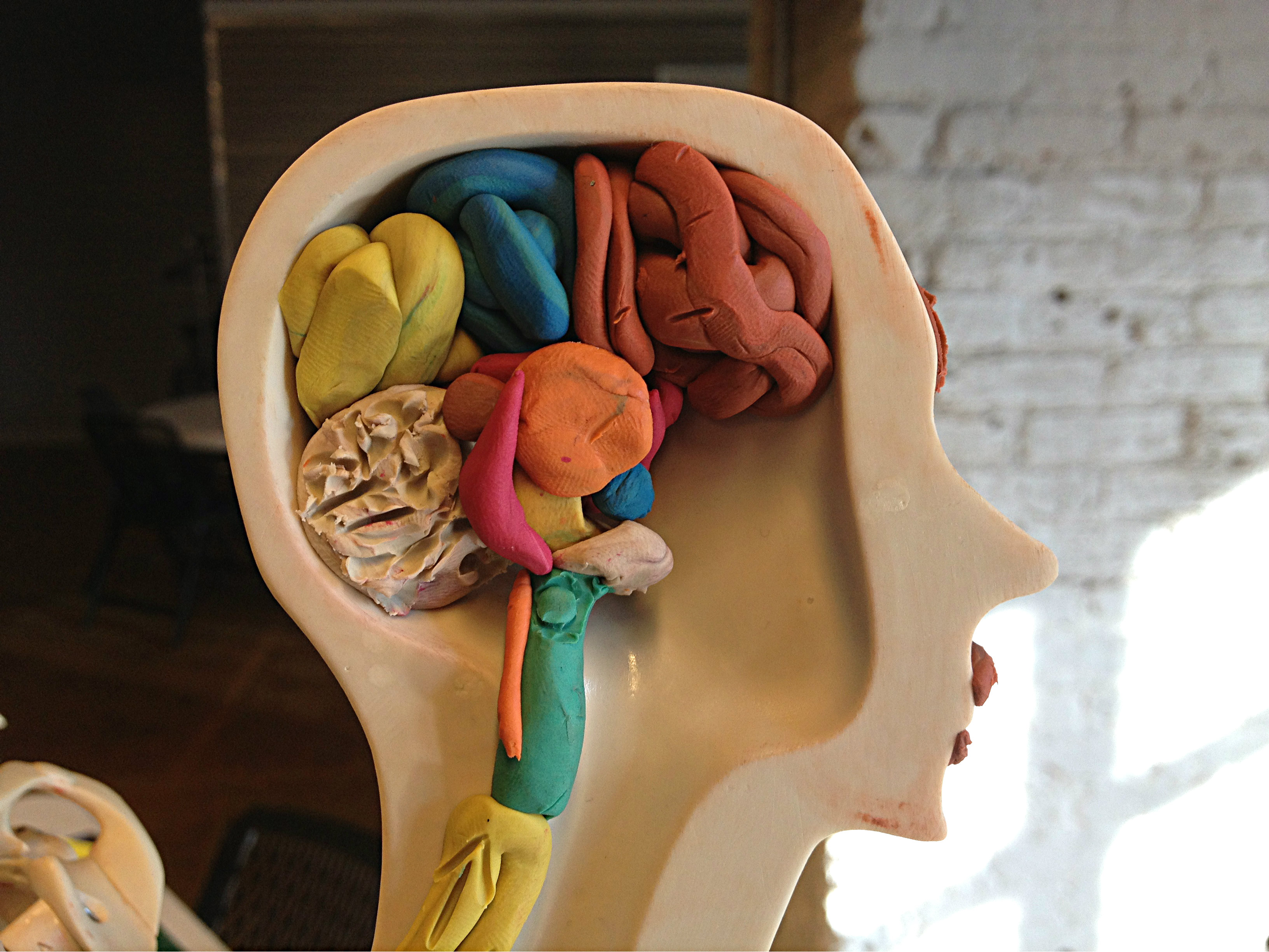

The students in this class are building a human from scratch. The “human” is a 29-inch plastic skeletal model. The students construct blue veins, terracotta muscles, red arteries and more out of color-coded clay. They gently insert them into precise regions on the model. It’s a highly technical process.

Fleming circulates the room, making sure the students put the large veins in the right places on their model hearts.

The underlying philosophy of doing anatomy with clay is that the students build the systems of the body from the inside out. It’s a constructive process. Lesley Peterson, a former teacher who now works for Anatomy in Clay, says it is a meaningful experience for students to see a human cadaver, where the body parts are labeled, but she says there are things students can’t see, like where a muscle attaches to bone.

“I memorize it because I don’t see that on the cadaver,” she says. She says students also have to memorize what the muscle does - its “function,” in anatomy terms.

When building with clay, the students look at a picture of where the muscle attaches on the bones and build the muscle in a few seconds.

“I put it on the model and then I see what its function does,” she says.

She says that takes critical thinking and exercises different parts of the brain.

Aarika Capra, an anatomy teacher at Brighton High who has used the models for several years, says the real power of learning anatomy through clay is that the students apply what they see to their own bodies and predict what the action of their muscles will be.

“My kids being able to predict what a muscle does based on where it is on the body, I think that’s a really big takeaway that they use all the time in whatever sporting event or hobbies or clubs that they’re in,” she says. “They’re using those muscles.”

Research shows, by touching and building the anatomical models, the information is easier to retain and prompts more questions.

Instructor Teri Fleming encourages the students as they build one of the most difficult muscles in the digestive system – the small intestine The average man is 5’10’’. His small intestine is 21 feet long. The students have to calculate it to the scale of their model, and their height. For Aarika Capra, that’s a terra cotta string stretching from her head to the floor.

“Having 6 feet of small intestine made me glad I was short,” she jokes.

Fleming tells them jaw-dropping facts like, if you took the human intestine – from mouth to anus – and stretched it across the massive studio, “our mouth would be stuck to that wall and our anus would be stuck to that wall,” she says, pointing to a wall far away. The students snicker.

Through building body parts, students can see how pancreatic cancer spreads so quickly, or how, permanent heart damage starts if young people haven’t shed their pre-pubescent fat by age 14.

What’s striking is how normal it becomes to talk about how the body functions. When a student whispers that she lost her urethra, Fleming simply says, you can always build another one! Fleming tells them the class is a way to pass on health information students need, which may be hard to talk about elsewhere.

“Anatomy is an awesome class,” says Aarika Capra. “Every student needs to understand how their body works, how to take care of it, common things that might go wrong, and treatments or procedures to fix those, and a lot of them, with the models, you can model it, act it out.

Fleming sprinkles the class with lots of ideas to help students understand anatomy, like writing persuasive essays about a neglected body part, or snapping fingers to reflect how the heart works. She also builds a number of defective hearts out of clay, and asks students to diagnose the problem, much like a real doctor would do.