Anderson says that to be a great teacher, one has to find out what is important to each student in their lives outside the classroom.

“A student whose mom or dad are addicted to drugs, a student who goes home and the lights are out or there’s no heat or there’s no food, they don’t care about high stakes testing, they don’t care about trying to get to college, they don’t care about the diploma, unless they have somebody who can sit down and takes the time to tell them they love them to death, and that they appreciate them,” Anderson says.

Anderson, who is African-American, teaches ethnic studies at Denver’s Martin Luther King Jr. Early College and also trains teachers in “cultural competence,” how to better understand the role of privilege, race, gender difference and power in society, and the classroom.

Anderson says that talking with a student about their issues makes all the difference. He likes to remind students they are strong, telling them “that you are standing here in front of me is a testament in itself to your strength.”

Building relationships with students of color

This method is called culturally-responsive teaching and is comprised of four elements: Building relationships, promoting resilience and making lessons rigorous and relevant.

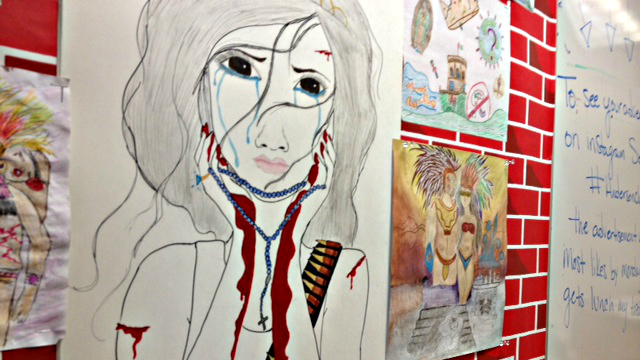

A peek into Anderson’s classroom shows how he cultivates these tenets of culturally-responsive teaching.

He moves around a lot, makes the students laugh, asks the kids for their opinions. Anderson is what researchers call a “warm demander” -- tough and disciplined but strongly identifying with his students.

Before even getting into academics, Anderson tells students about attending his great-grandfather’s funeral and lays out a visceral picture of the poverty in his hometown.

The kids know about his life and he knows about theirs, like when he tells them about how he went to eat at “Popeye’s” and they all nod when he asks if they eat there.

It is the little things like his references to places kids eat, thanking them frequently for the good work they do, asking them questions about their lives, and telling them about his --these things build the relationship. By sharing details about his own life, and asking them what is going on in theirs, he’s building relationships that researchers say are particularly important to students of color.

Anderson builds resilience by praising students for their work despite all of the challenges waiting for them at home.

Relating to students lives

Once students are engaged, Anderson demonstrates relevance and rigor by challenging the students to think deeply and showing them how subjects in school matter in their lives.

For example, in one lesson, Anderson played excerpts from a speech by Black Panther Huey Newton to get students talking about how they feel being black in America today.

Too often, Anderson says, teachers don’t explain how the material in class is relevant to their students’ lives. As the students listen to speeches and talk to Anderson, it’s apparent that for a lecture like this, it does help to be a teacher of color, from a similar background.

“And I had that in me too growing up,” Anderson tells the class. “I don’t know why I felt so weird and why at a point it almost started to piss me off, hearing about MLK again, hearing about Rosa Parks again, it was like, I could have sworn my people did more than this? We had to have done more. It made me feel ashamed of who I was. And this is what Huey [Newton] was talking about.

Letting students talk about race

Anderson is open to taking students questions and comments about race. He asks if they have ever felt shame about the skin they are in.

Student Camri Jackson says she’s never felt ashamed but she’s always had to prove herself.

“Which is why I am the student that I am because I feel that there’s this underlying stereotype that students of color are the same, and so I’ve just worked my ass off to make sure it’s not standard for me,” she says.

Anderson acknowledges that his being black helps him connect, but he stresses that it isn’t necessary. He says the techniques he uses would work for any teacher, and to that end he trains his colleagues.

White teachers can learn method, too

In fact research shows, students of color would like a teacher who looks like them but they’re equally fine with a teacher of any race who loves and respects them. The challenge for many white teachers is how to get that across to students if their differences get in the way.

In Denver, teachers can take workshops in in more specific types of instruction and support to address those differences. DPS’s head of culturally responsive education Darlene Sampson and her team of trainers are actively trying to give teachers the tools they need for relating better to students, drawing on a growing body of research about what works.

“I always tell teachers who say to me, this is one more thing,” she says. “We’re so overwhelmed. We have state testing. We have all these expectations and responsibilities. So I always say to them ‘equity’ is not the carrots. And it’s not the salad on the plate. It is the plate. “

This is big and complex stuff to confront and change, according to Beth Dorman, who for many years, taught a multicultural perspectives course at Regis University. And the work can be difficult and intrusive for teachers.

“We have tears, I mean, we have anger every single time we teach this class,” she says. “And the results may not show up for a while. But more and more teachers in Denver, Cherry Creek and Aurora are taking it on so they can make the classroom experience work for students of color as well as it does for their white peers.

“The feedback that we hear from our students who are practicing teachers, is that the opportunity to think deeply and work deeply with these issues, has quote un quote changed their lives and changed their practice,” she says.

Becoming "culturally responsive" a lifelong process

It’s still though, a small percentage of teacher overall who have ever taken the training. And trainers stress it’s not a quick fix, it’s a lifelong process.

Marne Gulley, who trains Denver teachers about these issues, sees an urgent need for schools to change the dynamic so students of color can succeed. When children of color aren’t being connected to and affirmed, Gulley says the consequences are dire.

“I see students graduating from high school reading at a second grade reading level,” she says. “When students play the game and can squeeze by with just D’s in their classes and then are just passed on to the next grade but never are challenged academically or connected to, we’re never going to be able to take kids to these higher places academically if we don’t start with them as individuals.”