Part of a small neighborhood near the former Colorado Fuel and Iron steel mill in southeast Pueblo could become a national historic district. As a post-World War II working class neighborhood, it’s not the kind of place you’d normally expect to get this kind of recognition. It’s long been known as Old Bojon Town after the Eastern European immigrants who came to work at the mill.

A block of modest well-kept mid century homes along with the neighborhood school, church and bar form the potential historic district. It’s steeped in the traditions of the immigrant steelworkers and families who built these homes by hand and never left.

Several generations have grown up dancing, singing and playing traditional guitar-like instruments like the brac or bugaria with the Okolitza Tamburitzans - a folk troupe that has met at the old St. Mary’s school building for decades.

Pueblo City Planner Wade Broadhead says historians are recognizing the importance of working class neighborhoods like this.

“It looks exactly the way it did when it was built in 1949-51. The lawns are perfectly manicured, the architecture hasn’t changed much. The metal lawn furniture is outside in mint condition. It is really a living historic neighborhood,” Broadhead says.

Joe Kocman grew up in Old Bojon Town. He says everyone had nicknames: “My dad’s nickname was Moon…My Uncle Albert was Jonesy and Ray Krasovic was Killer and he won’t tell why it’s Killer but that’s been his nickname ever since he can remember…My brother’s nickname was Pudgy.”

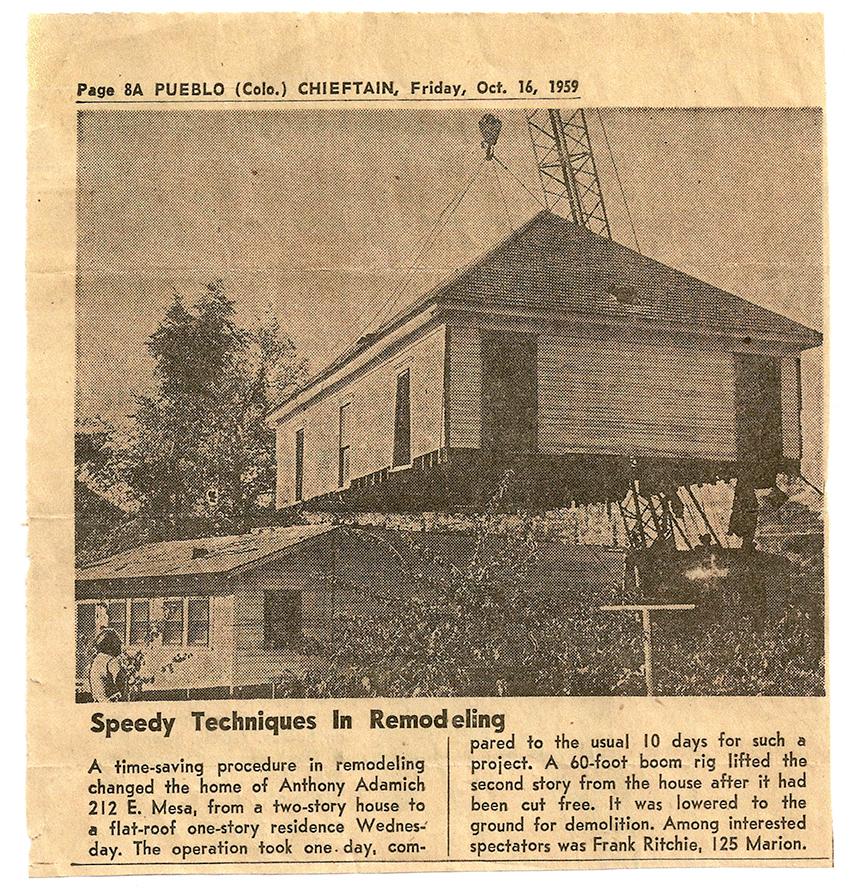

An active guy in his early 60s, Kocman can tell all kinds of stories about the homes and the people who live in them. Like the house that had its second story removed in 1959 when he attended the parish school across the street.

“They just cut around it and used a crane to lift it off. We were all in school when they did that and Karla that lives there -- her teacher wouldn’t let her them go up to the window to watch them take the roof of her house, all the other classes got to watch,” Kocman says.

The school itself was built using bricks that came from the smokestack of a nearby smelter that closed in 1908 and was taken down in 1923.

Kocman says, “the church gave the kids and the families a penny a brick to clean the bricks that were used in the school building.”

But now the slag left behind by that old smelter has put the area onto the EPA’s list of potential Superfund sites due to possible toxic lead and arsenic levels and proposed construction on I-25 could threaten homes on the edge of the neighborhood. These two issues were among the reasons residents came together a few years ago to form the Eiler Heights Neighborhood Association.

At about the same time, Broadhead, the Pueblo City Planner, asked if they were interested in becoming a historic district. Kocman’s wife Pam says she wasn’t surprised by that - even though she didn’t grow up here, she knew it was a special place.

“Everything about it is unique, you know, the music and the food and the way they kept up the yards and the neighborhood and how everybody would visit with everybody and continue the story telling,” she says.

It’s those stories that were a big part of the survey that showed the neighborhood’s eligibility for listing on the historic register. Dawn DiPrince directs the El Pueblo History Museum, and helped locals turn their memories into what became the community’s larger narrative. She says architectural historians often look to written records and books to do their research for a project like this and that can leave gaps.

“History books are often written about people like Rockefeller. They’re written about millionaires, bazillionaires or generals of armies. They’re rarely written about working class men and even more rarely are they written about working class women.”

Old Bojon Town is a working class community. Joe Kocman remembers a steelworker who liked to sit on his front porch at night and sing and play the button box accordion.

“The problem was he couldn’t play and he couldn’t sing. It was enough to make the cats howl. But he was out there every night singing and playing that button box and the neighbors would cuss him out,” Kocman says.

Eilers Place is a popular neighborhood bar that Kocman's grandmother "Pepa" started more than 80 years ago. It's across the street from the church and the school, which wouldn’t fit with today’s zoning codes. Joe and Pam Kocman ran Eiler's Place for 15 years. Pam Kocman says three or four generations of the same family would sometimes come to the bar.

“They’d bring their kids in and we’d take their pictures of the new babies and we’d put them up on the wall - we have books and books of these things. Kids are always welcome and the kids love to come because the customers would buy them candy or Pepa would feed them,” she says.

Two of Joe Kocman’s cousins took over Eiler’s Place in 2006, so it’s still in the family and the traditions continue on. The close knit nature of Old Bojon Town is important as they face the uncertainty of the Superfund process. The public comment period just ended and more testing is expected by this fall. Meantime they’ll meet to decide whether or not to officially apply for historic designation.

The song heard at the end of the audio piece is the Song of Bojon Town, written by Daniel Valdez, and incorporated into the historical oratorio, Song of Pueblo. Historitecture, a historic preservation consulting firm that performed the survey of Bojon Town, produced the following video.

4/21/2022 UPDATE: The neighborhood was considered eligible for the National Historic District designation, according to Broadhead. However, he said some residents were told by their insurance agents that they would not be able to get their properties insured if they were considered historic. Not all insurance companies have this policy, but the effort to get the historic designation was dropped.