Several measures are on the ballot this fall to raise funds for public schools. For some, it could mean increased taxes. Also, up for a vote: transparency in contract negotiations between unionized teachers and the districts they work for.

Several measures are on the ballot this fall to raise funds for public schools. For some, it could mean increased taxes. Also, up for a vote: transparency in contract negotiations between unionized teachers and the districts they work for.

CPR News education reporter Jenny Brundin spoke with "Colorado Matters" host Ryan Warner about education measures on the ballot.

Ryan Warner: Jenny, every election year school districts can go to their voters for money to help maintain schools. They usually have to do this when they find state funds lacking. First, help us understand how Colorado schools are doing financially now.

Jenny Brundin: In 1995, other states on average spent about $700 more per student than Colorado did. Nationally, spending has risen so that by 2012, on average, the rest of the country spent $2,600 more than Colorado did. That’s because here, spending has consistently declined. In fact, Colorado spent less per student in 2012 than it did 17 years earlier, in 1995.

That trend reversed a bit last year when the Legislature decided to repay about a tenth of the $1 billion it cut from schools during the recession.

Yes, that’s right. They paid back $100 million. Lawmakers felt compelled to do something for schools after voters resoundingly rejected a ballot measure that would have put $1 billion back into schools. Tracie Rainey, who heads up the Colorado School Finance Project, surveyed all 178 of the state’s districts. This year, she says, she sees a new level of desperation. Many schools had already dipped into reserves and cut to the bone during the recession and so Rainey says this local election is their only hope.

More: Election 2014 coverage | Voters guides

"They are really feeling that if they aren’t successful at the local level, the cuts they are going to have to be making are going to be pretty devastating," Tracie Rainey says.

So how many districts are going to voters this year?

There are 26 districts asking for property tax hikes and 17 districts seeking bond approval this year. Districts are asking for a total of $1.7 billion. It’s the biggest financial request since 2010.

Which district is looking for the most money?

Boulder has a $500 million bond for school buildings. Adams 12 Five Star has the largest property tax request. It would raise $15 million annually, to update textbooks, keep teachers, and bring back programs that were cut.

Give us an idea of who’s asking for money and why?

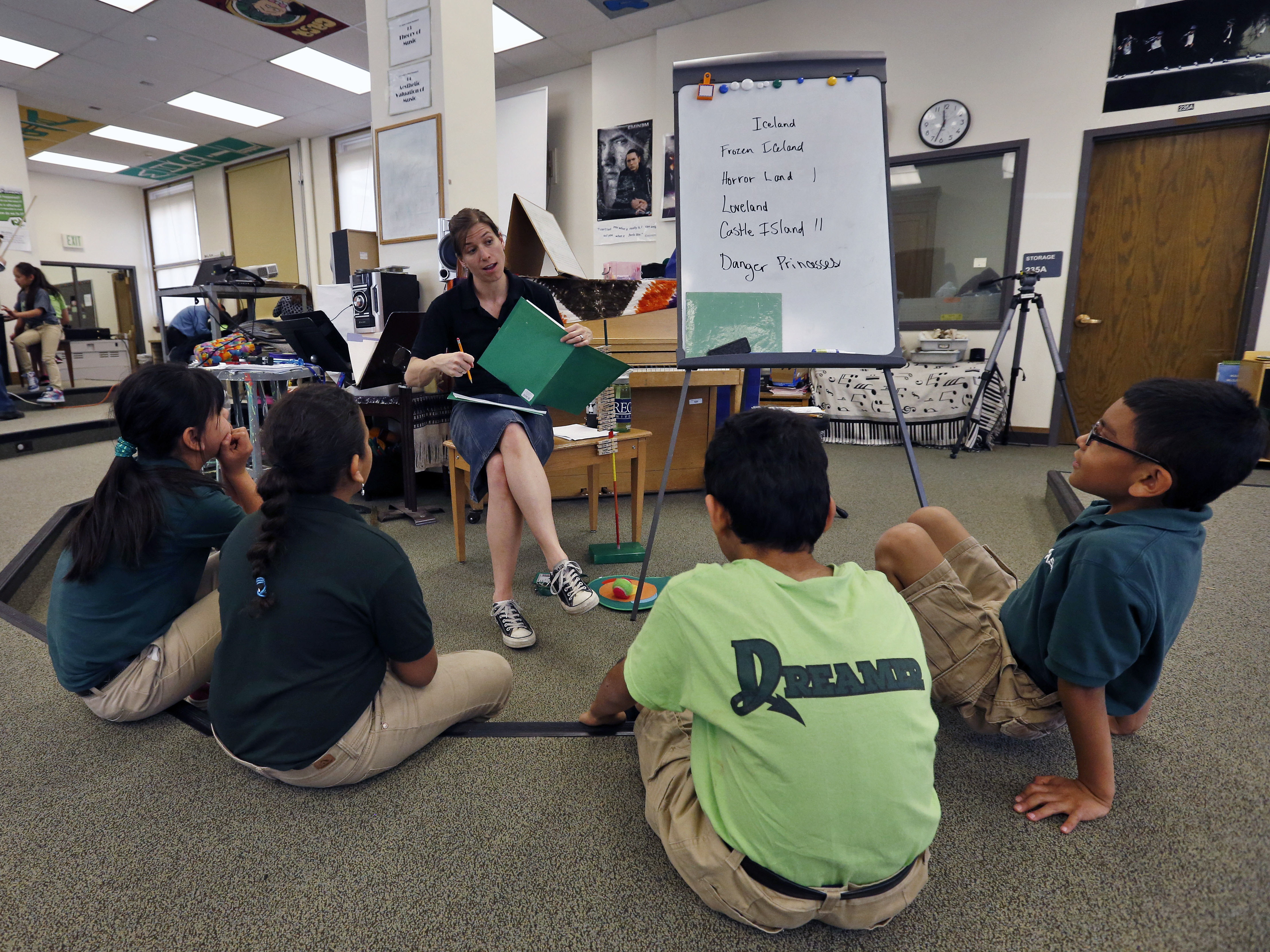

Well, you have some larger districts like Adams 50 in Westminster that have both a bond and property tax on the ballot. They’d like to have air-conditioning in their elementary schools, replace aging roofs, wiring, and sewer systems in some schools. The property tax hike would keep them from having to increase class sizes and from having to cut arts, theater, and music programs. Several rural counties like Garfield want to use the money to help boost teachers’ salaries so they’ll stay. Starting salaries in some rural districts are about $28,000.

Rural districts in particular are struggling?

Yes. Arickaree School District, about 1.5 hours east of Denver, is emblematic of many rural districts. It’s a single school -- preschool through 12th grade -- built on some farmland in between two towns: Anton and Cope. It’s about 10 minutes from a grocery store and 1.5 hours from Walmart. That’s how Superintendent Dave Clarkson describes it.

How many students in the school?

They have 106 students, about eight fewer than last year. Business Manager Sara Walkinshaw says every time a family leaves the area, it hits the school hard.

"When we lose students, even three students, there goes a teacher’s salary," Walkinshaw says.

Their ballot measure is for $250,000 – about $59 a year for owners of a $100,000 house. If the measure doesn’t pass, she says they’ll have to lay off two or three teachers. The district has already combined first and second grades. They’d also likely have to cut one bus route, raise prices on school meals and possibly go down to a four-day week.

So it sounds like the property tax hikes aren’t for funds to be used for new technology and programs.

No. The ballot measures largely are not for new programs; they are to prevent future cuts. Walkinshaw, says with rising fuel costs, inflation, and the like, schools just can’t make it.

"We’ve been having to utilize some of our reserves just to keep going. The revenue from the state and county is just not enough to cover everything," Walkinshaw says.

While there is no organized opposition to the tax hikes and bonds across the state, we do know they’re tough to pass, especially in struggling farm community where unemployment is high and incomes low. Some districts have failed several times in the past but have no choice to try again.

In general, how have property tax hikes fared at the ballot?

Of Colorado’s 178 schools districts, 40 districts passed a hike between 2009 and 2013, while 138 did not. So generally, it’s a tough sell.

Proposition 104

Proposition 104

Proposition 104 would open up all school board meetings in which teachers unions and other employee groups collectively bargain over contracts. These are already open in about a dozen districts in Colorado?

Yes. Because Colorado is a local-control state, each district gets to decide whether to open negotiations. So Colorado Springs, Poudre, Jefferson County, and Douglas County are some of the districts that already allow the press and the public into these negotiations.

But this proposition would make it law that all districts would have to open these negotiations to the public. What’s the meat of what goes on in these meetings?

It’s where they hammer out salaries, benefits, hours of work, and other working conditions for teachers and other school staff.

Where did the measure come from? Who wants it and why?

Denver-based free-market think tank the Independence Institute helped push it to the ballot. Bills to do the same thing have been shot down several times in the Legislature. In the voters’ Blue Book it states that the Prop 104 upholds the public’s right "to be informed and provides additional public oversight of government spending.” Jon Caldera of the Independence Institute says secrecy is the enemy of good government.

"That contract is 85 percent of any school district’s budget. So imagine if the state Legislature decided to do it’s budgeting in the dark -- people would be rightly incensed. So in this contract, we learn where taxpayer money is going to go, how are kids are going to be taught, and how our teachers are going to be compensated," Caldera says. "This is public business that should be done in sunshine."

All the major newspapers have also come out in support of it.

And who opposes it?

The main teachers union and the Colorado Association of School Executives are backing the “No” forces. The name of their campaign is “Local Schools, Local Choices.” They argue that deciding to open negotiations should remain a local decision. School districts and boards also believe it would put them at a disadvantage because they’ll have to make public their strategy sessions. They also say the language is too broad. It states that any time a public bargaining agreement is “discussed," not just negotiated, that has to be made public. So they’re worried that hundreds of informal discussions that take place now would need 24-hour public notice. Bruce Caughey with the Colorado Association of School Executives says that will cause lots of confusion and inefficiency.

"If you present a proposition to be presented to the people of Colorado, you should get it right from the outset," Caughey says. "It is astonishing to me that the special interests pushing this proposition didn’t reach out to find out how things really work inside a school district."

Caldera says if there are problems, they can be fixed by the Legislature. Caughey counters that to pass something that has to be fixed is not a good plan.

Amendment 68

Amendment 68

This next item isn’t actually an education issue per se, but we’re going to have you talk about it.

Yes. This is Amendment 68. It’s a measure that would allow for a casino at the Arapahoe horse-racing track. Supporters’ biggest argument is, they say it will pump jobs and millions of dollars into Colorado’s economy, including more than $100 million for public schools. The name of the "Yes" campaign is, in fact, Coloradans for Better Schools. The major backer is Twin Rivers Casino, based in Rhode Island. It owns the Arapahoe park.

What do opponents say?

Opponents are primarily the state’s mountain gambling towns -- Black Hawk, Central City, and Cripple Creek. They say it will drive them out of business.

The Aurora city council is divided on the measure. Some residents are opposed because they say a casino would worsen heavy traffic on the narrow 2-lane roads that border the race track. No money is alloted for infrastructure improvements to the roads, which would cost the city an estimated $62 million dollars.

What is the school community saying about this amendment?

A couple of weeks ago the Colorado Association of School Boards passed a resolution opposing citizen-led initiatives to fund schools with revenues from “sin” taxes. That includes alcohol sales, gambling, and recreational marijuana. The resolution states that sin taxes are a “fragmented” way to fund schools and amount to “bribing” the electorate. It says such measures aren’t solutions to the “continual underfunding” of K-12 schools and often fall short of generating projected income. The state’s largest teacher’s union, The Colorado Education Association, is neutral on the measure. So is the Colorado Association of School Executives, or CASE. CASE officials are worried that if they officially oppose the amendment, it could be misconstrued that they think there’s no need for more education funding. As they say, that could not be further from the truth. They want a steady, reliable source of funding for schools.

Denver’s Measure 2A

Denver’s Measure 2A

Turning to Denver specifically, there’s a ballot measure to reauthorize and expand Denver’s preschool program. Tell us about that program first.

In 2006, voters approved a sales tax increase to create a program that offers tuition credits for preschool for any family in the city. It is 12 cents on every $100 purchase.

And how has it worked?

The program has served more than 34,000 children. More than $50 million in tuition credits has been distributed. And signs indicate the program’s really helping kids get a head start on learning. Independent studies of the city’s third graders show students who participated -- had significantly better math and literacy scores. Supporters say it’s so successful that DPP (Denver Preschool Program) has been used as a model for other cities across the country.

So the ballot question, measure 2A, asks voters to renew the sales tax and raise it 3 pennies to 15 cents on purchases of $100 or more. If they approve it, the tax would be in place for the next 10 years. So tell us how much new revenue they project and what that new money would be used to do.

It would raise a projected $11 million annually. During the recession, the program had to make cuts to year-round preschool. That left a lot of parents in a jam. There is a big demand for full and extended day programming, and the Denver Preschool Program and city leaders want to restore summer programing that had to be cut.

"It’s not good for kids who have made a lot of gains through that 4-year-old preschool year to suddenly be out of pre-school and there’s some summer learning loss associated with that," says Jennifer Landrum, director of the Denver Preschool Program.

Is the program open to all families?

Yes, though the lower your income, the higher your credit. The average credit is $290 a month. And this is another reason that they’re asking voters for the 3-cent bump. Colorado ranks near the bottom (45th out of 50 states) in the nation for preschool affordability. The average preschool in Denver costs $800 per month.

Any organized opposition?

There’s no known organized opposition to the measure.