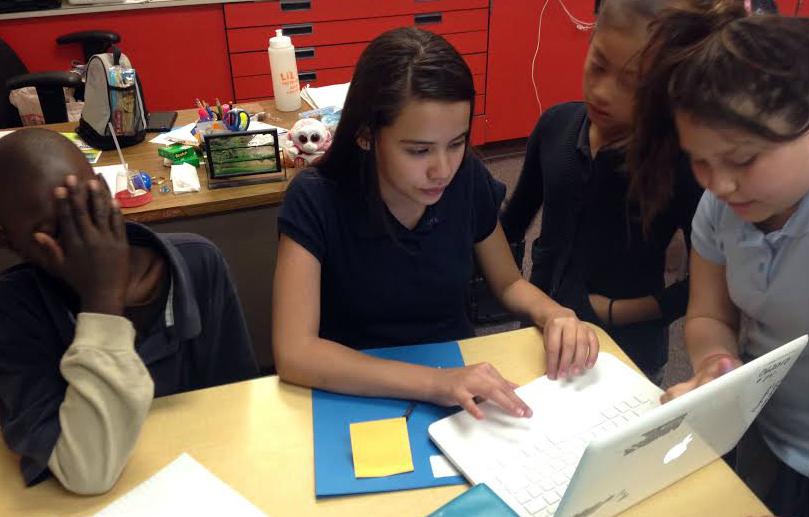

Sandra Baca has a big personality.

“I’m kind of sassy to some people,” she says, her long brown hair pulled loosely into a high ponytail.

And the fifth grader's guard is always up. If somebody’s rude to her, or gives her what she calls "a dirty look," they get a quick "you got a problem with me?"

In third grade she said that to a girl she’d never seen before. “She’s like ‘who do you think you’re talking to?’ ” Sandra remembered.

Turns out, the girl was just visiting the school. Sandra says she didn’t mean to do it but the damage was done -- she got in trouble. She’s still working on controlling her quick temper, but says her family shares her tough, matter-of-fact style.

She tries to leave that behind every morning when she walks into Room 115 at John H. Amesse Elementary School in Denver’s Montbello neighborhood. Something on the wall always catches her eye: a bright yellow problem-solving poster. It’s part of the PATHS program, which tries “promoting alternative thinking strategies.”

The poster is divided into red, yellow and green categories that help students assess step-by-step how they’re feeling and if they’re about to get into a conflict, how to calm down. Students carry little laminated replicas of the poster in their pockets, in case they need it for quick reference.

“It's kinda like, ‘whewwwww,’ Sandra says as she exhales. "Let me calm down.”

The PATHS curriculum is a comprehensive program, developed in the 1980s, that promotes emotional and social competencies. It’s in about 1,500 schools across the country -- including some in Denver's Montbello neighborhood. Multiple studies show PATHS reduces aggression, depression and behavior problems in elementary school-aged children.

A growing number of educators, spurred on by a growing body of research, believe that teaching these social skills to reduce aggression not only keeps kids out of trouble well into their adult lives, but helps with academics.

May 22: Single mom learns to manage toxic stress and tighten family bonds

May 20: Research shows stress can be toxic for kids who live in poverty

May 19: Poverty changes a mother's brain and her baby's as well

“They are so many other things that we have to combat before we can even get to, ‘here’s the instruction piece,’ ” says Sandra's teacher, Dawn Jackson. “How do you sit down in the classroom for 30 minutes without having to get up and do stuff. How do you not yell out? How do you talk to people in a ‘Hi, good morning,’ social kind of thing? There are so many steps to putting together the whole student, as opposed to just academics. It’s a lot."

PATHS lessons focus on self-control, emotional understanding, positive self-esteem, relationships, and interpersonal problem-solving skills. Jackson says strategies for reducing conflict are practiced throughout the day.

PATHS lessons focus on self-control, emotional understanding, positive self-esteem, relationships, and interpersonal problem-solving skills. Jackson says strategies for reducing conflict are practiced throughout the day.

“It’s ‘how do you solve problems with your groups? What do you say? How do you make sure everybody’s on task?’ Jackson says. “I make sure that they get into a large group with a project, they actually write out a ‘constitution’ or expectations, so they know, so they pull it out and say ‘OK remember if we [get frustrated], we take a deep breath and get calmed down so we can get clear and focused.’ ”

Aggressive behavior, sleeping through tests

Jackson has tried to create a safe, open community in Room 115.

In the morning, she does a “check-in,” giving kids the opportunity to share how they’re feeling. The kids can monitor their emotions with clothespins, which is not part of the formal PATHS program. If a child is mad or frustrated, he or she can take a clothespin with their name on it and put it on “red.” Then they can go to a table at the back of the room. Jackson knows then to leave them alone. The student can take five minutes to write in a journal that the Jackson doesn’t read. She checks in with them when they’re done.

Jackson says she sees a fair amount of aggressive behavior in the school including gossiping and bullying. She’s lived in Montbello for 17 years and knows a lot of her students’ lives bring a lot of stress. She says just getting up in the morning can be stressful because many students are responsible for themselves -- and their siblings.

A month ago, during testing, the big problem she was seeing was kids sleeping in class.

“During standardized tests kids are sleeping because they’re just not getting enough sleep,” she said. “They come in aggravated already because they’re late, and so they tend to sort of lash out at other students or at the teacher because they’re feeling anxious.”

If they weren’t able to get their homework done, “that frustration builds, so they might yell out, throwing things down on the table, knocking over chairs. I have a few kids that just run ... out of the class.”

Students then, usually just need time to calm down and then they are brought back to the class. If they’re not hurting themselves or other students, the idea is to have them in class as much as possible.

Some kids are defiant, refusing to do what the teacher asks. Some teachers get defensive, taking the challenge to their power personally. Jackson says over the years, she’s learned not to, surmising that the defiance comes from feeling a lack of control over the situation at home – the frustration comes out at the teacher at school.

“I’ll ask, ‘is there something I can do? Is there something you need?’ ”

Troubled kids

The numbers of kids feeling troubled in this part of Denver is high. In fact, in a screening of more than 2,000 Montbello kids, the results were astounding: a third of elementary students got in a fight in the last 12 months. Twenty-five percent of middle schoolers said they had emotional problems. That compares to six percent nationally. Thirty-six percent of middle school students reported conduct problems, compared to 11 percent nationally.

The scores also showed significant numbers of students were at risk for serious violence a year later. So a team of researchers at CU Boulder is trying to answer this question: is it possible to bring down youth violence and other problem behaviors here by 10 percent by 2016?

PATHS – in four Montbello Elementary schools - is one small part of an ambitious community-wide intervention plan in a neighborhood that deals with ongoing gang violence, high unemployment and poverty.

Finding compromise, empathy

Two times a week for 20 minutes a day, Jackson reads her class a story with lessons from the PATHS curriculum. The stories focus on things like self-control or the one today about two friends solving a conflict using the “golden rule.” She asks the class what the expression means.

As she reads the story, Jackson takes breaks to let the class talk about how each boy is probably feeling and what a compromise is.

Sandra Baca uses this analogy: “Say like one person wanted a candy bar and the other person wanted a candy bar and it's a king sized candy bar, they each could get half, and that would make them equal,” she says. “That's a compromise.”

They also talk about how empathy goes a long way.

“That’s the biggest problem [with] how conflict escalates,” Jackson tells them, “because the other people don’t know or you don’t feel like your side is acknowledged.”

But sometimes – out on the playground - and the messages they get from home – make following PATHS hard.

“Sometimes they [teachers] say if a kid hits you, tell the teacher, but the teachers don’t do anything and they say tell the principal but they don’t do anything,” Braulio Olivas says.

Sandra, the self-described sassy one, nods.

“My mom always just tells me to sock ‘em in their face, but let them make the first move first, and then you hit and then after you hit them, you call her, and she’ll back me up,” she says.

But Sandra says the PATHS stories have helped her in other situations like saying sorry to her best friend after a fight or to help calm herself when her sister is annoying her.

“PATHs really helped me with that understand now how to relax and bring myself down and not really think about it,” she says.

Classmate Jeramiah Nichols gets into disagreements with friends sometimes. He says he’s taken deep breaths, changed the subject, and just the other day, he found himself in another disagreement.

“I just got up and moved for a minute. And I came back and he was really fine,” he says.

PATHS shows results

These kinds of programs are showing results, researchers say in multiple studies. Not just in lower rates of aggression, anger and depression – but a better understanding of how to recognize cues about how others are feeling, and how to resolve conflict with friends.

A meta-analysis looking at multiple studies found that participants in “social-emotional learning” programs compared to controls, showed an 11 percentage point gain in achievement.

Studies show for this approach to work, this type of thinking needs to be infused in every grade. At John Amesse Elementary, not all teachers are using PATHS equally. Jackson, who used to teach third grade, notes that it was harder to implement PATHS starting at the fifth grade level. She says it was easier to start with third graders and then advance each year. One study documents positive impacts of social emotional programs on preschoolers.

Dawn Jackson hopes next year full implementation can happen because for her, it's personal. Before Room 115, Jackson worked as a juvenile correctional officer.

“Then when I went to the adult system, I would see [the same people] there just coming out,” she says.

She saw a lack of education and self-esteem, of not knowing how to interact positively with people.

“You just get tired of seeing that. And I’m like, ‘you know what, we need to get it before it gets to that point,’” she says.

So Jackson became a teacher. When she sees her students act up, Jackson tells them she knows where it could lead -- and lets them know there are other options.