The small 600-person town of Silverton is doing some soul-searching after an EPA-triggered spill of 3 million gallons of orange wastewater last summer.

The question is how to limit hundreds of other abandoned mines from negatively impacting rivers and streams in southwestern Colorado.

Proposed Good Samaritan legislation has been floated as one possible solution, although some mines in the area are seen as too complex to be addressed by this fix.

Outside the area, the answer might seem simpler: pursue a National Priorities Listing under the Environmental Protection Agency’s Superfund site program.

San Juan County Commissioner Ernie Kuhlman says that the county is going to become "more knowledgeable about Superfund." Local leaders are planning on a fact-finding mission Nov. 9-13 to visit other towns like Leadville and Idaho Springs that have handled clean-ups through a National Priorities Listing.

But there’s a history with this issue in Silverton.

In 2012, the EPA dropped a listing bid lacking support from town and county leaders, reported the Silverton Standard.

"The Silverton Town Council and the San Juan County commissioners have refused to back Superfund listing, expressing concerns about the stigma often associated with such a designation," wrote the paper in its April 26, 2012 issue.

Two years later, Mark Esper, editor and publisher of the Silverton Standard, wrote an editorial after the spill to encourage town leaders to pursue a Superfund priority listing. He says the town already has a stigma after 3 million gallons of orange wastewater from the Gold King Mine polluted the Animas River.

"We have to address the problem. By looking like we’re dragging our feet--that’s the real bad publicity that we’re getting right now," he said. "I think we have to face the reality that this has affected everyone from here to Lake Powell," said Esper.

Town leaders like San Juan County Commissioner Ernie Kuhlman do say there has been a shift in mindset.

But in a town with a strong independent streak, Superfund status would mean an even bigger partnership with the EPA. And Kuhlman said he’s worried that Silverton wouldn’t have control over the boundaries that the federal government would propose for a Superfund site.

How narrow or broad the boundaries are could dictate how long Silverton stays on the list.

"How wide do they expect this thing to get? How much money do they have to spend to try to override mother nature?" he said.

Kuhlman highlights another concern: Superfund sites aren’t always super-funded. Congress has to appropriate funds. And then there are other questions. Like what would superfund designation mean for property values?

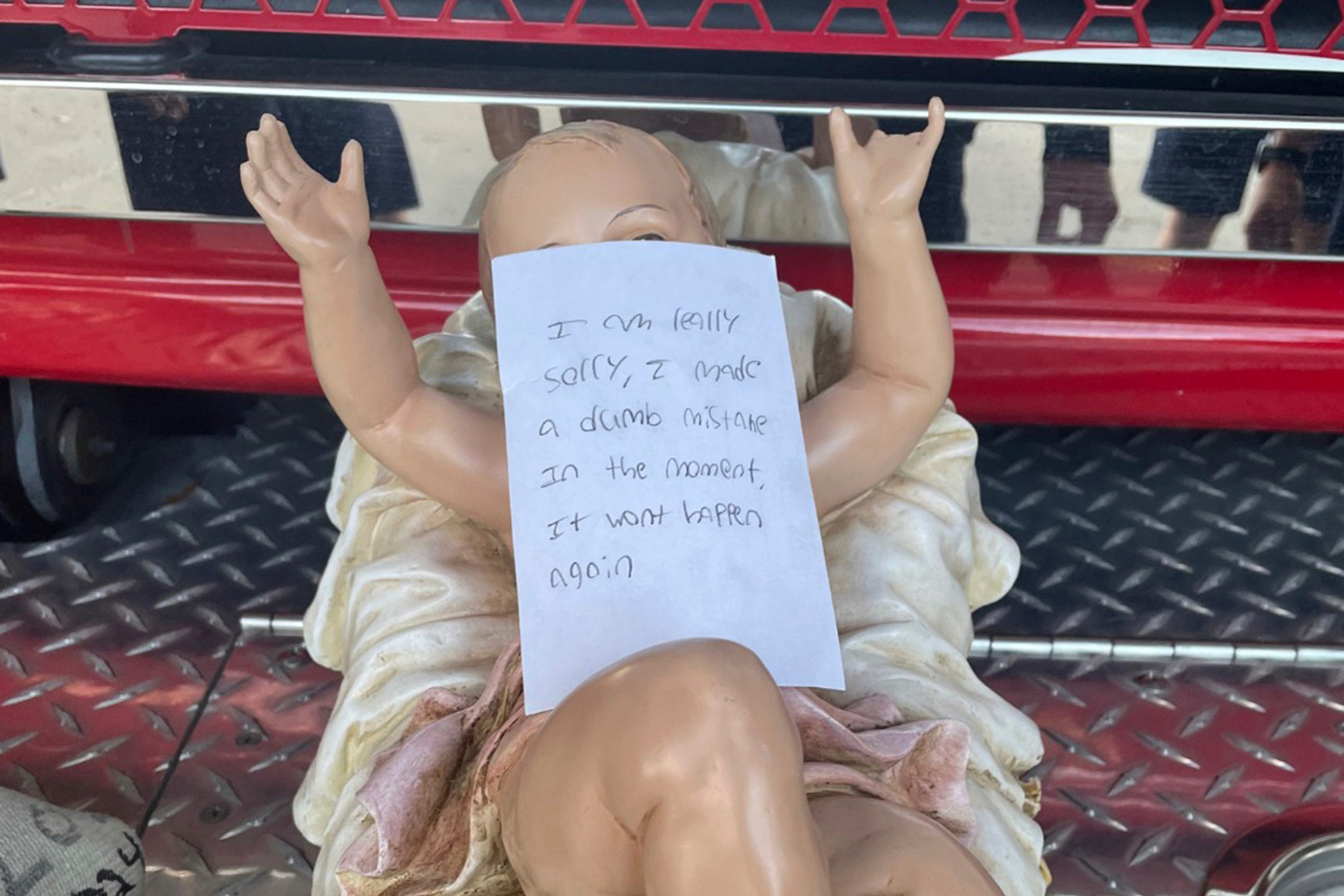

Walk around town and the conversations about Superfund status are wide-ranging and opinions are strong. Some are sharply in favor the idea. Others are dismissive of the plan. A small minority believe that the EPA intentionally caused the Gold King Mine spill.

DeAnne Gallegos with Silverton’s Chamber of Commerce said since the spill, trust of the EPA is low.

"Trust is a key word. But trust is not purchased, nor guaranteed, it is earned," she said.

To that end, Silverton and San Juan County leaders will continue to discuss the issue with EPA officials. The agency recently responded to a detailed list of 16 questions about the Superfund listing process and its impact.

Right now there is no timeline for making a final decision.