Parents out there can probably relate to this: You’re riding in the car, your kid in the backseat is listening to music on their phone, with earbuds. And you can practically hear it in the next county.

Yep, your child has the volume up really, really loud.

The World Health Organization warned earlier this year that more than a billion teenagers and young adults worldwide are at risk of hearing loss due to exposure to unsafe, damaging levels of sound from personal audio devices or at noisy entertainment venues. The warning was based on data from middle- and high-income countries, like here in the U.S.

Recently, I spoke with my daughter and some of her friends who listen to music all the time at their school, Stanley British Primary School in Denver.

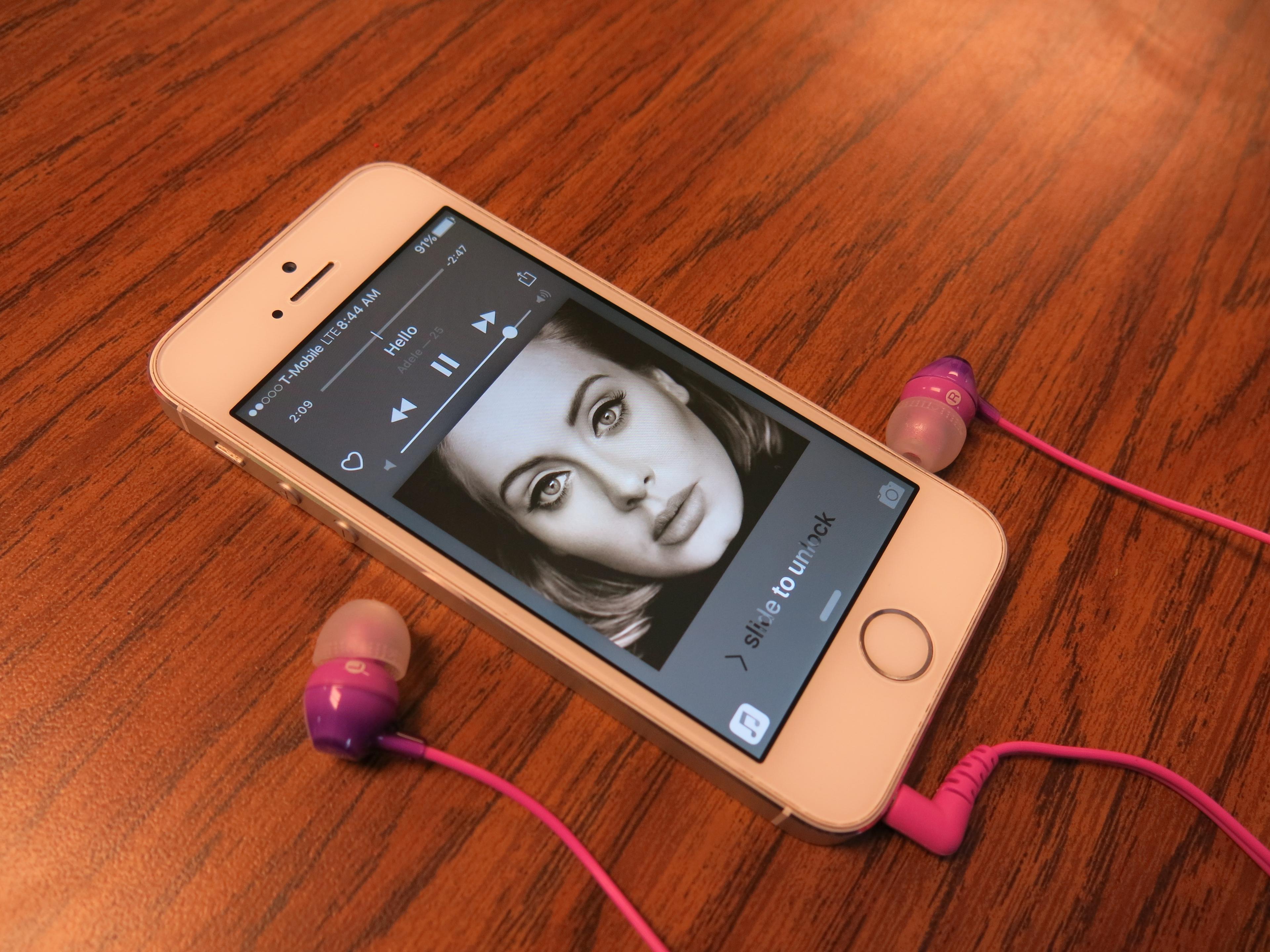

The six students -- Georgia, Mia, T.J., Elliott, Nati and Julia --all say they like to listen to everything from Drake to Adele to One Direction and often on their phones, with earbuds.

So how often a day, how many hours?

"Probably about 30 minutes," said Nati.

"Yeah, I listen to [music] a lot," Elliott said.

Julia said she typically listens "about an hour, maybe." She then amended her answer to "an hour and a half," as her friends laughed.

T.J. said when he's in the car with his family, sometimes his mother will let him know the volume on his device has crossed a line. "She's like 'turn it down, T.J.! You're not the only one in this car,'" he said.

Nati and Georgia like to crank up the music too.

"Sometimes it’s turned up really loud and my phone sometimes gives me notifications, saying listening to music too loud will give you hearing issues," said Georgia. "But that’s only happened a few times.”

Georgia says her mom, Jenny Cargile often complains. When I talked to her mom myself, she doesn’t mince words on her feelings about earbuds.

In a recent survey by the American Speech Language Hearing Association, the majority of parents questioned were worried by how misuse of phones, laptops, tablets and video games could negatively impact their child’s hearing.

Cargile agrees with that. She limits the amount of time her three kids can listen, and has gotten rid of all the earbuds in their house except for one pair for use when exercising. She does let them listen on noise-cancelling headphones, but monitors the volume and tells them about the risks.

"What are you doing to your ears, when you're listening to that, at that volume?" Cargile asks. "We don't know. We don't know what damage it's doing."

Denver Public Schools audiologist Lisa Cannon says parents are right to be concerned. "I'm saying they should be worried. Definitely," she said.

Cannon said she’s seeing more teens with minor hearing loss. She tries to teach students, at a young age, to be vigilant about protecting their hearing. She said hearing loss is cumulative.

"The hearing loss from exposure to noise is irreversible," Cannon said. "So, if you think about it in that way, we're kind of looking at potential for an epidemic of hearing loss among this generation."

Listen To Your Buds

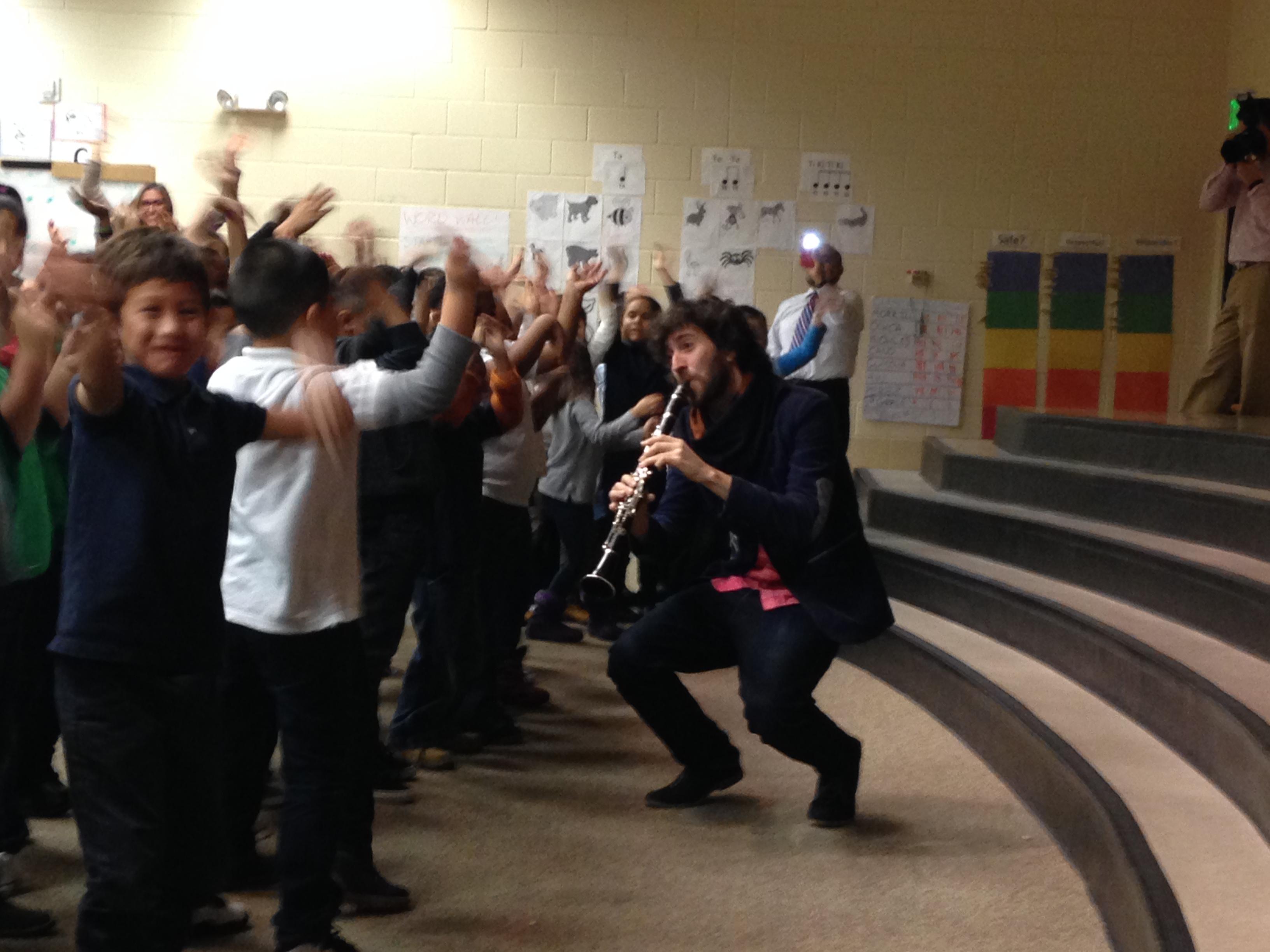

To get that message out, the American Speech Language Hearing Association brought a series of concerts to Denver schools. It's part of a national campaign called "Listen to Your Buds."

At Greenwood Academy in northeast Denver, New York-based jazz musician Oran Etkin and his trio, including a bassist and drummer, get an auditorium full of first and second graders dancing around, clapping their hands.

Etkin is the creator of a music teaching method called Timbalooloo. He gets the kids to pretend to be a giant ear, waving their arms like the sensitive hairs inside called cilia. He teaches about the damage that can be done when the noise is pumped up too much.

"I need to turn the volume...?" Etkin says. Then the kids join in: "...Down!"

Etkin says hearing loss is an occupational hazard for musicians.

“I know a lot of musicians, a lot of my friends have lost a lot of their hearing," Etkin says. "Definitely musicians are put in difficult situations sometimes when we have to perform in loud settings.”

He tells the kids they can avoid the same fate when they're older by learning to appreciate their hearing now.

"One thing that I really want them to get is the joy of listening," Etkin said. "And the joy of hearing. So once they value their hearing then they can really protect it."

Back at my daughter’s school, I ask her and her friends if they worry that listening to loud music from their earbuds is going to affect their hearing.

"I don't think so," said Georgia.

"It's possible, if you listen to it really loud a lot of times," Elliott said. "But if you only do it a couple of times or for your favorite song, I don't think it will cause any hearing problems when you're older."

I pressed the point about whether it could cause future hearing problems, but not one says yes when I ask for a show of hands. Audiologists say sadly the people who might lose some hearing won’t realize the risk until it’s too late.

Tips For Parents, Kids

Cannon, the DPS audiologist, has some advice for parents and children.

She urges parents monitor the time their kids spend under the headphones, on earbuds, or listening to other electronic devices, to make sure that their kids are listening at a safe level. Generally, she said, audiologists recommend setting the devices volume capacity at 50 to 60 percent of volume capacity, or less.

Cannon said it's a good idea for children take breaks from listening.

"Don't let them have long periods of exposure," Cannon said.

Cannon added that there are output limiting applications and devices that allow parents to set restrictions on their phone. She recommended parents get a good set of earbuds or headphones that don't allow leakage of sound. "Often earbuds don't fit well with the ear, so they turn it up, and that's when danger is present," Cannon said.

A set noise-cancelling headphones is a good investment, since it avoids the leakage of sound that often prompts listeners to turn up the volume too high.

Also, parents can model good behavior, Cannon said. If they're not showing good listening habits themselves, it's often difficult to ask children to do something the parents aren't.