Go into any school -- any kindergarten classroom for that matter -- and you see the banners: Harvard, CU Boulder, Colorado State, School of Mines. The four-year college mantra is deeply embedded in the Colorado and American psyche.

But what if that's not the right destination for a high school graduate? What if there was a way for them to focus on science, technology, engineering and math jobs that don't require a bachelor's degree?

"I think that when parents think about what they want for their children, they think about a four-year degree," says Angela Baber, director of STEM Education at the Colorado Education Initiative, a nonprofit working in partnership with the Colorado Department of Education, educators, schools and districts. "But that hasn’t worked for a lot of our students."

This disconnect is reinforced as the cost of getting a four-year degree becomes more and more prohibitive. And it's having an impact on Colorado's economy.

The state has one of the most highly-skilled labor pools in the country, but businesses here still have to recruit out of state to find workers. And there's a particularly big shortage in "middle-skills" – which are needed for trade-type jobs that require more than high school education but less than a traditional bachelor's degree.

“We’re not even close to filling the gap,” says Mark Alpert, chair of the board of the South Metro Denver Chamber of Commerce, who heads up the organization’s STEM initiative.

He heard recently from one employer who had openings for 100 tool and die makers. They could only fill one position locally. Ninety-nine new employees came from out of state.

“Those are technicians, they are not college-educated people but the skill is incredibly high,” he says.

But many high school students graduate not knowing that the largest share of jobs -- good-paying jobs -- don’t require a four-year degree.

Fifty percent of Colorado jobs are in these "middle skill" occupations. But only 42 percent of Coloradans are trained for these jobs -- jobs like computer-aided designers, auto repair diagnosticians, welders, machinists and biomedical equipment technicians.

In fact, half of all science, technology engineering and math jobs don’t even require a 4 year degree, just some post-secondary education such as a certificate or associate's program.

Many of those jobs "have upward salary mobility and upward career mobility. And so for a lot of students who want to try something before they invest in a four-year degree, that’s really the way to go," Baber says.

Shifting Awareness

A number of laws passed in the 2014 and 2015 legislative sessions aim to speed up the connections between industry and high school and post-secondary schools, sometimes by creating supports for paid internships, or marketing efforts for individual training programs. This helps students to see what the possibilities are. But the trick is to get their feet closer to the door of potential employers.

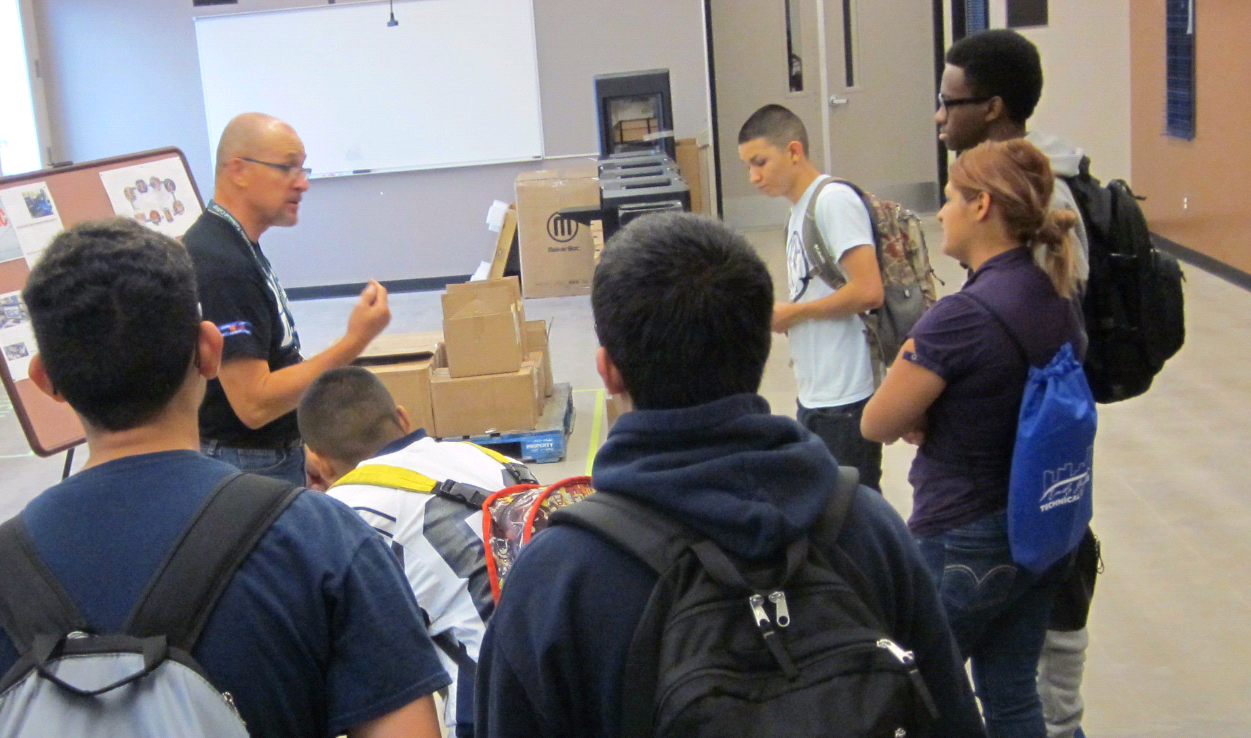

That's where Manufacturing Day comes in. Groups of high school students from Denver take a three-campus tour of schools that offer middle skills training, to get a taste of the types of well-paying, skilled jobs that are in high demand.

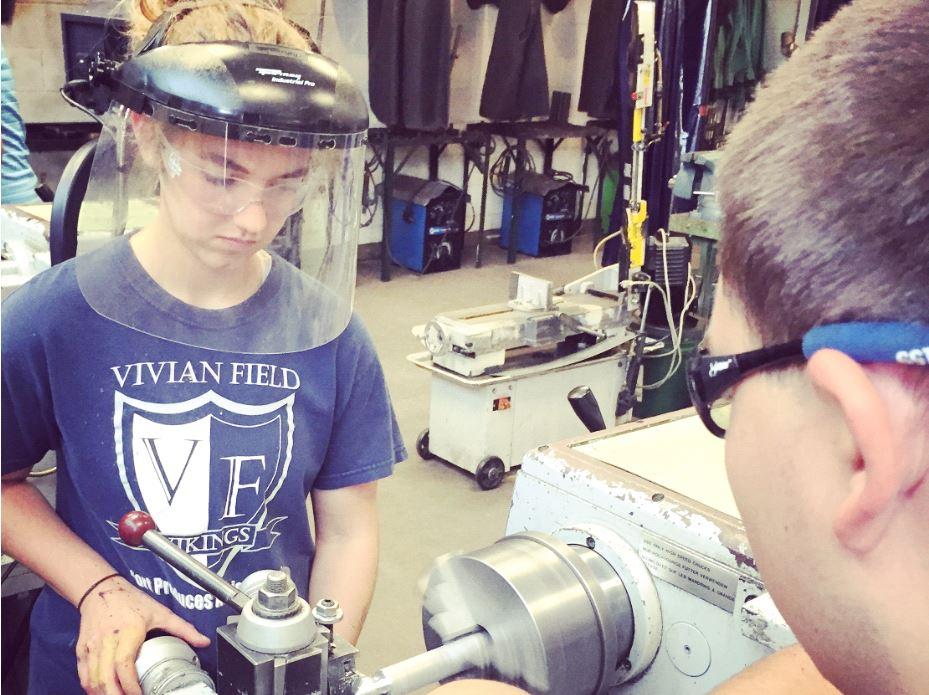

During the tour, Sugent is as animated as a kid in a candy shop while he shows groups of high school students the heating and air-conditioning (HVAC) lab, and brand new labs for advanced manufacturing, computer aided design and drafting, and welding.

That last one catches Marciano Melendez's eye.

"It just looks like a lot of fun and it pays a lot," he says of welding. Middle-skill jobs can pay, roughly, between $40,000 to $80,000 and higher.

"It ain’t your grandpa’s factory," says Sugent, a manufacturing veteran who has managed people, processes, and systems in industries from heavy equipment assembly to microelectronics, computer controlled machining, military weaponry, wind energy composites, and medical equipment. He tells the students the school’s multimillion dollar equipment investments will prepare them for a good life.

"Everybody that graduates from this program goes straight out into a job," he says.

Then the tour moves to the Community College of Denver. There, because the demand for machinists and welders is so great, students in their program get jobs after one or two semesters.

Stepping Stones

Tour guides also tell the students that if they choose to get more education, credits are transferable to the other campuses like the Community College of Denver’s two-year program in engineering graphics and mechanical design.

High school senior Ahmed Clift likes that there are options.

"All minds think differently," he says, adding that not everybody wants to go to a four-year college.

Clift loves math and is asking lots of questions about measurement in a CCD engineering graphics class.

"I like architecture and drawing designs and stuff and what they do is almost similar. They make the designs from the calculations," he says.

The last stop on Manufacturing Day is Metropolitan State University, where the students look at products made from 3D printers and machines to test the strength of advanced composites used to make bridges, among thousands of other products.

For many students, the tour opens up a whole new world of possibilities.

For most of high school, Anay Olivas says she never considered education after graduation. Now, she and her mom are stashing away part of their paychecks to to be able to afford what’s to come.

When her tour group stops at Metro’s 3D printing lab, something resonates: She learns that the world’s first 3D printed titanium rib cage was recently transplanted into a man with cancer.

Her dad has cancer.

"He doesn’t have that much time to live so I think it’d be cool to figure out some things that would help cancer patients in the future," she says. "I’m a hands-on person, I like using my hands and building stuff."

Metro offers a certificate program in advanced composites materials manufacturing or additive manufacturing engineering, which includes 3-D printing. If students are interested in being a manufacturing engineer, the university will begin offering a four-year degree in Advanced Manufacturing Science next fall.

'I Want To Build Something'

At the end of the tour, high school senior Irving Valenzuela is beyond amazed by the multi-million dollar machinery he’s seen on all three campuses.

He’s spent his life staring at Denver’s gleaming skyscrapers, it’s bridges and restaurants. That's sparked lots of questions and wonder. And today, he has a glimmer of what his future can be.

"I want to know who the people are who are building these beautiful things around me," Valenzuela says. "What kind of tools do they use? What kind of training do they have? What are their lives like? "It’s amazing being here and seeing all these machines and what goes into building the city I love."

Colorado’s push into middle skills training isn’t just tours for high school kids. In Poudre and Delta, high schools, in conjunction with local businesses, are offering courses in advanced manufacturing.

"The advantage of learning in high school is that post-secondary costs money," says the Colorado Education Initiative’s Angela Baber.

Classes also give interested students a jump-start on training.

“It’s really getting them access to the actual technical tools and machines that they would be using on a day to day basis so that they graduate with that experience which gives them an edge,” says the Colorado Education Initiative's Liz Kuehl.

Across Colorado, there are other experiments: a welding training center for high school and post-secondary students set up inside a metal fabrication company. A high school focused on construction and automotive training. Two public high schools will open next fall where students – in six years -- can earn an associate’s degree in STEM in high school, called P-TECH.

In 2014, The Colorado Education Initiative released the STEM Education Roadmap, aimed at bringing together industry leaders, educators and others to build a better pipeline needed for the STEM fields.

But Mark Alpert of the South Metro Denver Chamber of Commerce says he's hearing from businesses that the change isn’t happening fast enough. He notes that half of Colorado's large districts are focused on developing connections with STEM and manufacturing industries and half aren’t.

“Boomers are retiring, the gap is enormous, and if not filled quickly enough, jobs will move out of state because there is not enough talent," he says. "We have one of the greatest economies in the country, and the way to sustain it is to get more talent, locally trained, locally educated and filling these jobs going forward.”

State and local education officials say developing a talent pipeline takes time – not even a year or five years -- because it’s not just about preparing pipeline for today’s jobs, but for a workforce we don’t even know we need yet.