Chances are you know one of the 5.3 million people in the U.S. living with Alzheimer's. By 2050, you may know a few more.

By then, according to an analysis of U.S. Census data, that figure is expected to triple as baby boomers age.

One of those boomers is Rene Gill, 64, of Lakewood. She worked for years for a construction company and in property management. Then something changed. She started losing short-term memory and struggled to finish tasks.

"I get discombobulated sometimes. Don't remember where I put things," said Gill.

She was diagnosed with early onset Alzheimer’s. Gill is upbeat and said she’s still pretty self-sufficient. But she can’t shake the thought that Alzheimer’s will eventually rob her of her very sense of self.

"I guess I'm more afraid of forgetting who I am,” Gill said.

Alzheimer's runs in Gill's family, and she worries it could be passed on to her two sons and four grandkids. That’s why she agreed to take part in a new study at the University of Colorado.

"I want this to be stopped," Gill said.

Funding for Alzheimer's research is dwarfed by the $200 billion the nation spends on care. But just as the ranks of Alzheimer's patients is growing, so is the political will to find a cure.

Colorado Research Focuses On Genetics

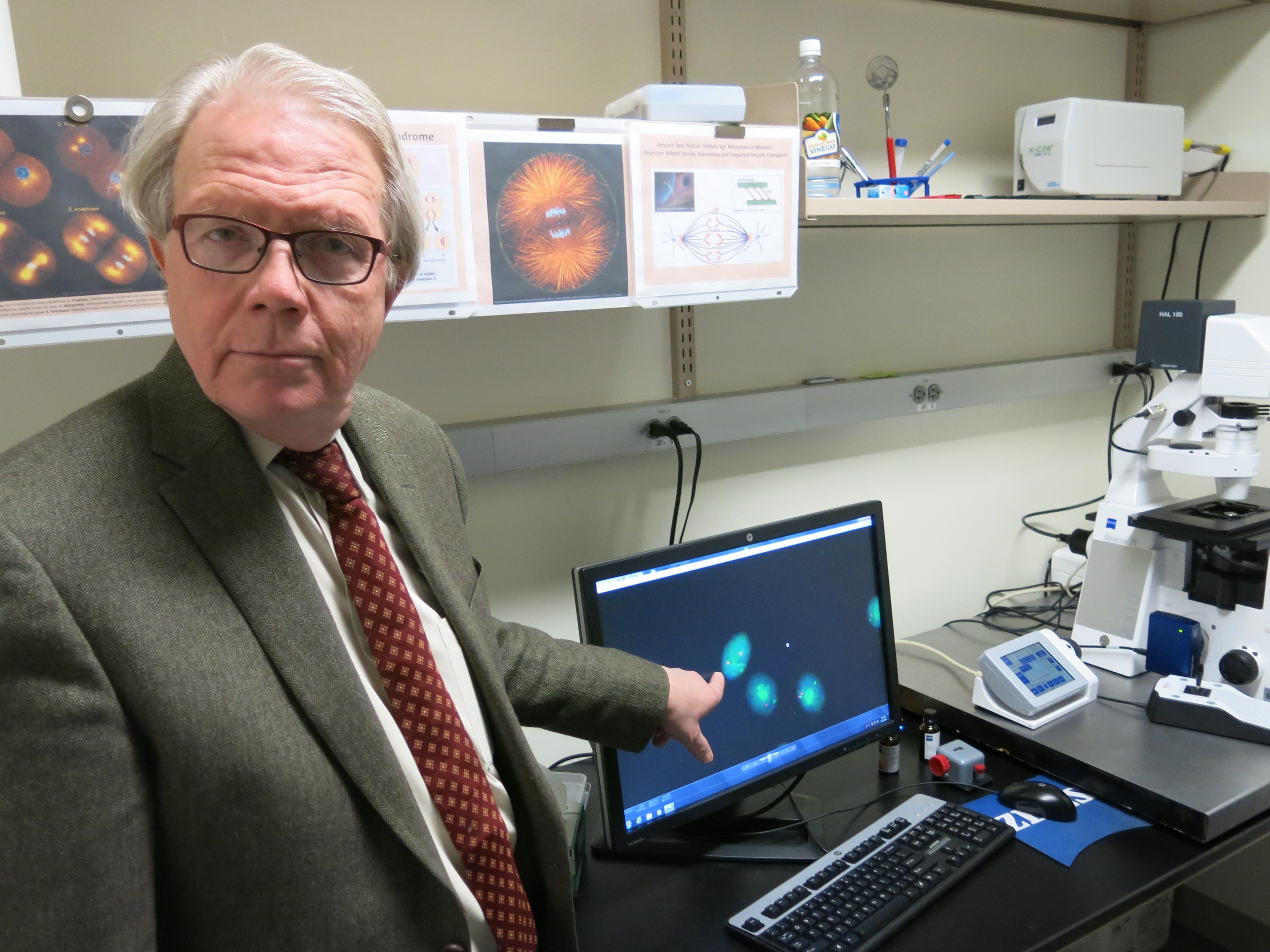

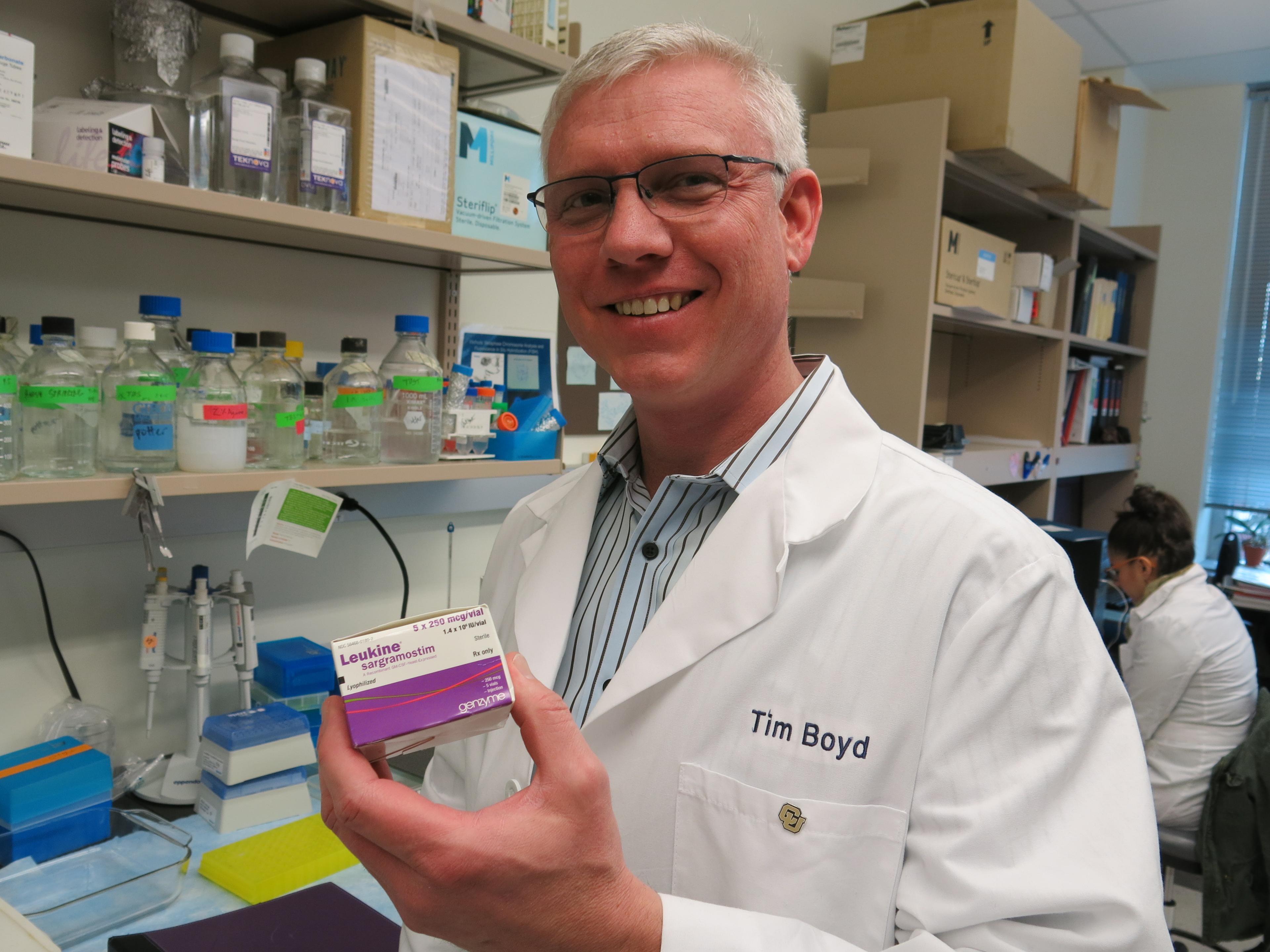

Gill volunteered to take injections for three weeks of a drug called Leukine. Eventually, 40 people are expected to participate. Researchers first tested it on mice with Alzheimer's. They say it reversed the deposits of a key protein found in plaques linked to the disease and reversed cognitive problems. Her doctor, Jonathan Woodcock, is helping lead the clinical trial.

"We're hopeful” the research will yield positive results, said Woodcock.

But he said unlocking the mysteries of this disease remains stubbornly tricky because it’s all about the workings of the brain.

"There’s no fact that we learn about the brain which is unimportant," said Woodcock. "This is the most complex thing in the whole universe that we know about.”

And everything researchers learn is just one more piece of the puzzle.

“We don't know which piece of data is going to take us over a building with a single bound," Woodcock said.

Researchers spanning the globe are fighting to solve Alzheimer’s. In Australia, a team of scientists are using ultrasound technology to treat the disease in mice. In England, a new vaccine trial is underway.

“They're a very special human population that gets early onset Alzheimer's disease," said Potter, who is also the Director of the Alzheimer's Disease Program at the Linda Crnic Institute for Down Syndrome. "The reason is very clear. They have an extra copy of chromosome 21 and that means they have an extra copy of the main Alzheimer’s gene, which is on chromosome 21."

On the other hand, people with rheumatoid arthritis are a low risk group.

“We began to look into this and make a long list of what was different about people with rheumatoid arthritis and focused down a couple of proteins that are increased in the blood of people with rheumatoid arthritis,” Potter said. The drug Rene Gill is on is a synthetic version of one of those proteins.

Politicians Take Notice

Potter said researchers are making progress. But just as important, he said, is that the political system is waking up to the problem.

At a campaign event last summer in New Hampshire, Republican Donald Trump called Alzheimer's a "tough, tough, tough problem." He responded to a question about future federal funding for Alzheimer’s research, calling it "a total top priority for me."

Democrat Hillary Clinton was even more specific last month. She called for $2 billion a year to try to find a cure by 2025.

“In 10 years we would know a lot more about it, we would have a lot more information," Clinton said. "We could maybe head off what's going to happen."

Last year, Colorado lawmakers approved about $500,000 for his center’s research. And at the national level, Congress, in a rare show of bipartisanship, recently voted to increase spending on Alzheimer’s research to nearly $1 billion a year.

"This is big," said Potter. "This is a recognition of the problem that is really there."

Potter said with more funding, researchers can explore new approaches. And one is likely to work, he hopes.

“The money will come because people realize that this is a problem that we absolutely have to solve," said Potter. "Otherwise it’s going to break our hearts and our bank books."

Dean Hartley, director of science initiatives for the Alzheimer's Assocation, is cautiously optimistic.

“It’s not a matter of if we’ll find an answer, it’s just a matter of when," Hartley said.

"And that’s completely dependent on resources and the funding.”

That, he says, depends on awareness and education. And on that front he sees momentum growing.