Every night, Thomas Peterson has two options. Should the homeless war veteran stay in a shelter, like the Denver Rescue Mission’s Lawrence Street Shelter in downtown Denver or its emergency shelter near I-70 in Montbello? Or, should he take his chances on the street?

Most nights, the choice is clear.

“I can't sleep on a mat on the floor because of my hip. It's easier for me to sleep on the sand,” he says. “It's a little more forgiving.”

Even if he were to get lucky and win a lottery-distributed spot off the ground in a shelter bed, he’d have another problem: where to keep all of his belongings. Shelters have some storage options for their guests, but generally allow only what you can carry.

- Portland And Denver Take Different Approaches To Homeless Camping

- Homeless Camps Cleared Out After Threat From City

- City Grant Helps Grand Junction Homeless Shelter Stay Open

So Peterson made his home at “Resurrection Village,” an empty lot at 25th and Lawrence. The Denver Housing Authority recently sold the land to a developer who plans to build market-price homes on it. Police cleared a tent village off the lot in December.

Still, the area has become one of a handful of gathering places for a segment of the homeless population the city describes as “service resistant.” Others find refuge on the banks of the South Platte River. They prefer to sleep outside, along with their shopping carts, bicycles and other personal belongings, vexing city leaders and neighborhood groups.

The situation reached a well-publicized head in early March when city crews cleared out a large encampment near Park and Lawrence. City officials said the camps had become a public health hazard. Nearby shelters -- Catholic Charities’ Samaritan House and the Denver Rescue Mission’s Lawrence Street Shelter -- supported the sweeps.

"We just want to be a good neighbor to everyone," Alexxa Gagner, director of public relations for the Denver Rescue Mission, said at the time. "It's an important step to clean up the area, to maintain a safe community and maintain cleanliness."

A month after the sweeps, the sidewalks are still clear near Park and Lawrence. And the city says it’s connected dozens of the campers to services to get them permanently off the streets. But some service providers say the sweeps were reactive, unproductive and indicative of what they see as the city’s piecemeal approach to addressing homelessness.

“We need a direction,” said Tom Luehrs, the executive director of the St. Francis Center, a day shelter on the fringes of downtown. “I think what's lacking right now is kind of an overall plan."

“Pack Up, Move. Pack Up, Move”

Robin Kendrick has seen much of the country since leaving his native Minnesota decades ago. In the roughly four months since he came to Denver, he described his days as a lot of “pack up, move. Pack up, move.”

On a warm afternoon last week, he was helping friends pack up belongings to makeshift bicycle trailers under a bridge near the South Platte River. He’s had his personal effects stolen many times over the years: pictures of a daughter he hasn’t seen in years, dozens of cell phones, vital identification papers.

He’s learned to pack light, picking up items when they might be of use and giving them away when they aren’t. If police don’t take them away, he says, other homeless people will.

“If you want to have it,” he says, “It’s got to be on your body.”

He means that literally. Even as the temperature rose above 50 degrees and felt even warmer in the spring sunshine, Kendrick said he was wearing three pairs of pants. A few days before, he said he wore seven shirts.

Peterson, the homeless veteran, was staying at Resurrection Village -- named after Martin Luther King Jr.’s 1968 tent village in Washington, D.C. he called Resurrection City -- a day after the March 8 sweeps when his belongings disappeared. He said he left them unattended, but hidden from view, for a few hours while he ate breakfast at the Rescue Mission.

"I keep my stuff nice and orderly so the public don't have to see it, if possible,” Peterson said. He said he had a suitcase and duffel bag stashed in a laundry cart with things like blankets, tarps, family pictures, and military papers. "My whole life was in there."

He said he was sleeping at the empty lot with others for his own safety -- and out of physical necessity.

"You can only go so far. I have a prosthetic hip,” Peterson said. “Sometimes, where I put my stuff at I'm stuck because my hip just won't go anymore."

Peterson checked for his belongings at a city warehouse where officials say they are storing the items collected in the March sweeps. People who were present when their possessions were taken were given a receipt and told they had 30 days to pick them up. Signs posted in the area gave the same information.

But because Peterson wasn’t there when his possessions disappeared, he didn’t have a receipt. He said the city had a duffel bag matching his description, but because he couldn’t describe its contents “down to the most minute detail” he wasn’t given it back. The warehouse’s staffer also questioned whether another homeless person may have taken his possessions, he said.

In either case, the event set him back in his quest to get into permanent housing, Peterson said.

"I came up here to relocate. And so far, all I've been doing is rebuilding,” he said. “All you can do is just keep trying. I can't replace the pictures and the memories and everything, but now I'm just brushing myself off and kind of going to keep going on and start all over again.”

(Peterson’s efforts to retrieve his possessions were filmed by Denver Homeless Out Loud, a vocal activist group that’s led efforts to overturn the city’s camping ban and pass a “right to rest” bill.)

The sweep in March wasn’t the first. Denver cleaned up another encampment near Curtis Park in December. After that, residents of the camp told the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado that their belongings had gone directly into the trash. That led ACLU to file a records request. Mark Silverstein, the group’s legal director, said he wanted to see if the city had violated constitutional protections against the unreasonable seizure of property.

“We’re all accustomed to parking our cars on a public street and leaving them unattended for hours, sometimes, days. No one would think those cars are abandoned,” Silverstein said.

He says the same goes for the possessions of homeless people, even when they aren’t with their stuff.

“Unattended property is not abandoned property,” he said.

The city’s response to the ACLU detailed the plan now at work to store items from the March sweeps.

Julie Smith, a spokeswoman for Denver Human Services, says one person has successfully retrieved their belongings since the March sweeps. She said city crews used great care in sorting through picked up materials to find possible valuables. They work with people who are trying to get their belongings back, she said.

“There was no way we were going to clear this encampment without offering the opportunity for people to have their items stored and for them to be able to come and retrieve those,” Smith said.

Shelters recognize the need for storage as well. The Denver Rescue Mission has some lockers for night guests and unsecured storage space in its day shelter. Samaritan House, across the street, has a shipping container in the parking lot that’s available to people staying there. But the demand greatly outweighs the supply.

“We are limited,” said Geoff Bennett, vice president of shelter and community outreach services for Catholic Charities. "We let them know how much space we have available and they can determine if they need to access [other options].”

Helping Those Who Don’t Want It

Storage at a shelter is only an option if you want to stay in a shelter in the first place. Julie Smith of DHS says city and shelter staff worked intensively to get campers at Park and Lawrence connected to services, but found many to be “pretty service resistant.”

Kendrick said he’s tried to stay in shelters in Denver, but even though shelters say they strive to keep their facilities clean and safe, he found them cramped and unhealthy. On top of that, he said he doesn’t like being told what to do.

“They manipulate people to think that if they don't do the program thing up there, then they are never going to make it,” Kendrick said.

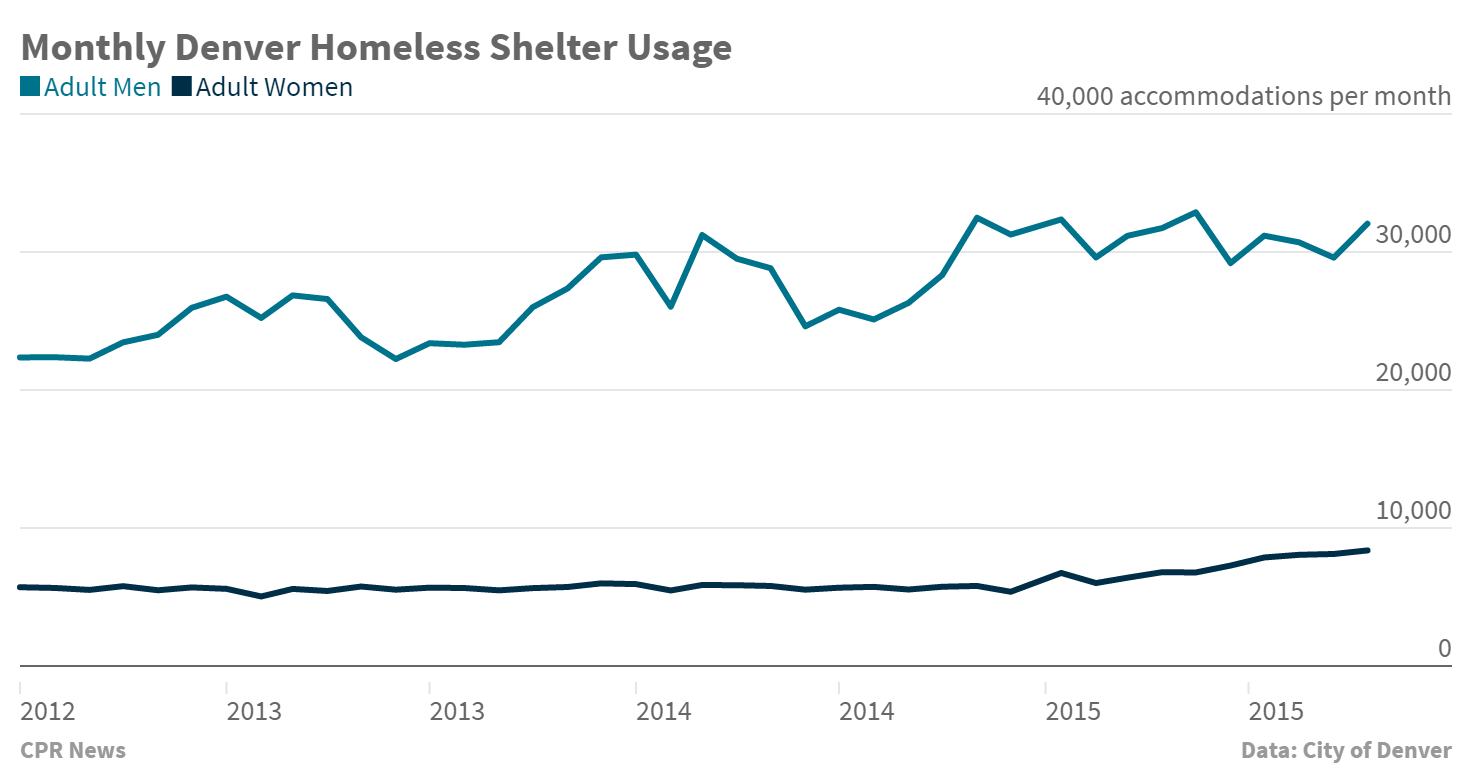

That sentiment exposes an ever-present problem for the city’s service providers: how to help a population that may not want what they have to offer. Even as the encampments grew downtown, the shelters were not full.

"It's hard to address every need of every single person, so we try to do as best we can,” Bennet, of Catholic Charities, said. “But there were safe places to sleep, as there are tonight, and there will be tomorrow night as well."

Bennet said families turn down open apartments weekly because they don’t want to abide by the shelter’s marijuana policy.

At the Denver Rescue Mission, CEO Brad Meuli said they face similar challenges.

“They are service adverse. And that's a tough group of people to deal with,” he said. “You can do drugs and alcohol on the street, but you can't do it in the Lawrence Street Community Center.”

The Rescue Mission’s spokeswoman Alexxa Gagner said they’ve recently seen an increase in the number of people enrolled in their long-term rehabilitation program versus the same time last year.

"We can't force anyone to come inside, but we can be encouraging and we can be available and open,” Gagner said.

Questions About City’s Direction

Other major service providers weren’t as supportive of Denver’s sweeps. John Parvensky, who’s been the president of Colorado Coalition for the Homeless for 30 years, said the sweeps merely addressed the symptom -- not the root cause of the problem.

“Ultimately, it's costly and counterproductive,” Parvensky said, while acknowledging that the camps couldn’t continue to grow with “no end in sight.”

“There are very few shelter beds, per se, in the city. Most are mats on the floor,” he added. “It's not a question of choice. It's a question of supply, adequacy and appropriateness of the supply of shelter."

Tom Luehrs, executive director of the St. Francis Center, a day shelter a few blocks away, said the entire community of service providers has struggled with how to help the “service resistant” homeless.

“We don't seem to be able to respond to this group of people who don't do well in shelters,” he said. “[We need to] respond to them in a way that's both dignified and acceptable so they are feeling like they have a space.”

Luehrs and Parvensky are members of the Denver Commission on Homelessness, a group of about 45 service provider executives and city officials. The commission started meeting every other month more than a decade ago as part of then Mayor John Hickenlooper’s 10-year plan to end homelessness. The commission is widely credited for improving communication among service providers.

But Parvensky says the commission is no longer driving policy decisions within the city.

“It's not part of the strategic planning process for determining how city resources are devoted to address homelessness,” Parvensky said. “At this point in time, I don't believe the commission is effective.”

Parvensky said the camps at Park and Lawrence were partly an “unintended consequence” of the city’s decision to support the Denver Rescue Mission’s efforts to build a day shelter. About three years ago, the Denver Rescue Mission had planned to build a women’s night shelter, said CEO Brad Meuli. But that plan was scrapped after opposition from the Ballpark Neighborhood Association, he said.

The city and the Denver Rescue Mission negotiated the day shelter “without a lot of input from the broader homeless service community,” Parvensky said. The new day shelter, which was itself delayed in opening over a lawsuit from the Ballpark Neighborhood Association, serves about 900 people a day.

“That's helpful to people who are already on the streets to shower, to get food,” Parvensky said. “But then they set up camp around there so they would sleep there during the night and access the day center during the day. Ultimately, that proved to be unsustainable and the sweeps were the natural result of those decisions."

Meuli, Denver Rescue Mission’s CEO, disagrees with that theory.

“People have been over in [nearby] Triangle Park and in this area for some time,” Meuli said. “A lot of those people would not come into the Lawrence Street Community Shelter.”

Meuli, however, also a commission member, said he agrees with the assessment that the city doesn’t have a strong focus. “I don’t know that there’s a master plan right now,” he said.

Still, the three executives all said they have high hopes for the future. Luehrs, from the St. Francis Center, said he’s seen positive changes at the commission since a critical April 2015 report from the Denver Auditor.

Mayor Michael Hancock’s office declined an interview request. But in a written statement, deputy communications director Jenna Espinoza said the city values the Commission on Homelessness.

“Our long term goal remains to assist each individual experiencing homelessness with their unique needs and connect them with the appropriate services to help them stabilize their lives. In 2016, the city will invest nearly $50 million on our homelessness efforts,” Espinoza said in the statement.