A visit to the library likely means checking out a book or movie. But the Denver Public Library says its central location has another job these days — it’s somewhat of a homeless shelter.

“That is a role that we have not asked to play, but are playing,” says Michelle Jeske, the city librarian for Denver.

When the doors of the library open at 10 a.m. a mix of people usually wait outside to be let in. Some have materials to return or pickup, and others are seeking shelter.

James Short, who describes himself as residentially challenged, is one of the group waiting to get in. He’s a writer, and says he comes to the library nearly every day to work. Without a home, “I’d be drinking a lot more Starbucks coffee and using their internet,” Short says.

Of the crowd gathered at the Central Library on this day, Short was the only one willing to be interviewed. One man said he was too high to talk. Another didn’t want the plasma center to know he was homeless or he wouldn’t be able to donate.

Elissa Hardy, one of the Denver Public Library's social workers, points out that the library is one of the few public bathrooms in the city. “We don't open until 10 a.m. [weekdays]. So as you can imagine, if you're leaving shelter at 5 or 6 in the morning, that's five to six hours that you don't have access to the bathroom.”

Two years ago, the Denver library didn’t have a social worker on staff. Before Hardy, she says that the Denver Library was doing the best it could. Now it’s becoming a lot more common position for libraries.

“When I started, this was the third city to get a social worker in the library,” Hardy says. “And now they are dozens around the country.”

Hardy admits she never saw herself working for a library, simply because she knew it as the place “where I could come to get my books.” But she’s here, saying hello to patrons as she walks the seven floors of magazines, newspapers, and (yes) books. The building is huge — 540,000 square-feet. In 1990, Denver voters approved a $91.6 million ballot measure to build the central library and other branch locations.

Today, Hardy says this multi-million dollar building is basically serving as Denver’s largest day shelter.

“I think that, the reason people often come here though, even though there are some other day shelter spaces, is because there are things to do. And there's resources, you can be another human in the community,” she says.

Hardy finds that most of the people who wait outside in the morning head straight to the computers on the fourth floor. That’s where some of them, like Short, do their work. Sleeping in the library isn’t allowed, but a few people appear to be nodding off at tables with their belongings tucked under their seats.

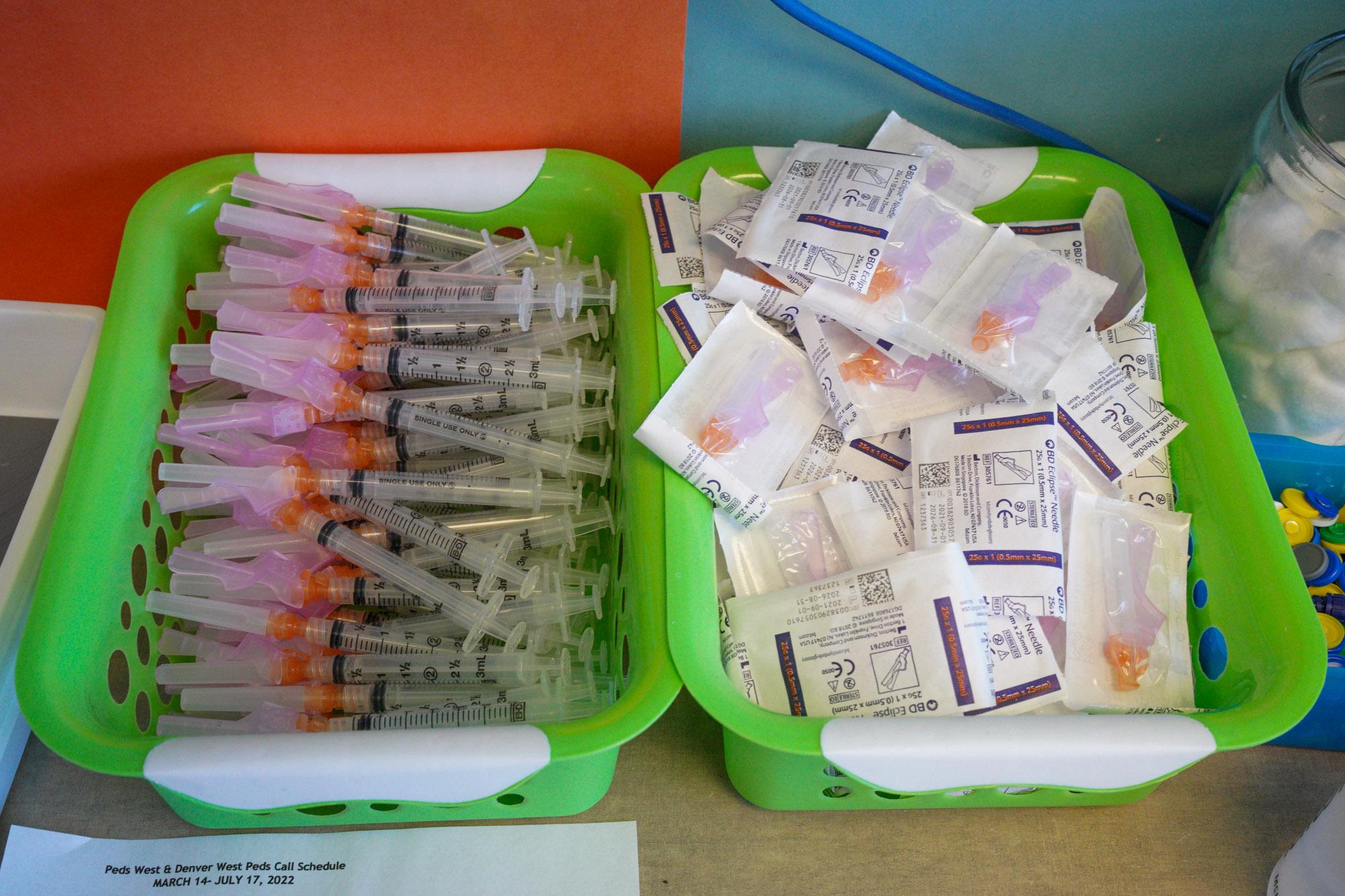

- An Opioid Death Prompts Denver Public Library To Keep Overdose Antidote On Hand

- With Crime There Rising, Denver's Central Library Seeks Ways To Serve Patrons Safely

Jeske, Denver’s head librarian, says the social workers were necessary to both better serve the homeless population and to help out the library staff.

“Those of us who went to grad school to be librarians didn't go to grad school to be social workers,” she says. “And were in fact, kind of bridging that role a little bit in ways that were not necessarily comfortable for us.”

The specialized help from the library’s social workers has been beneficial, but it's difficult to find a balance between being a library for everyone, Jeske says, and helping the homeless. They don't want priorities, like children's learning, to suffer. Hardy's position is seen as a way toward finding balance.

It wasn’t seen that way at first though. When Hardy started, she “certainly heard some staff having concerns that this isn't a social service setting” or worries that more people would be invited in. That pushback has softened, and she’s now seen as a resource.

Mary Stansbury, the head of the Library and Information Science Program at the University of Denver, says a social worker role is a natural fit for a library setting.

“Public libraries have for decades have been essential organizations, not just for homeless people but also as a conduit for connecting the agencies in whatever community that library might be in, that serve the homeless,” Stansbury says.

As Stansbury sees it, libraries provide a safe place. There are security guards, places to sit where you won’t be asked to leave and you’re off the streets. She admits, universities could better prepare librarians for that environment. She hasn’t found a library science program that has a class just on how to serve the homeless. The topic is explored in an existing DU class, and faculty are considering making it a requirement.

"It's certainly one that helps students dig pretty deeply into understanding, how do I empathize with this other person that may smell bad or, won't look me in the eye?” Stansbury says.

DPL social worker Elissa Hardy gets exactly where Stansbury is coming from.

“People don't go into the field of library science thinking they're going to be working in a homeless shelter essentially,” Hardy says.

In the summer, Hardy says many people without a home travel through Denver. Often the first place they go is the library. It could be to find a book. But maybe it's to ask, where are the food lines? Where can I find a shelter? And she says, the library is here to connect people to the resources they need.