Aspen is a place known for jet-setters come from across the world to ski and play. And where worker bees come from across the Roaring Fork Valley to cook and serve wealthy second-home owners and tourists alike.

What’s less well known is that wind, hydropower and biogas — all renewable sources of energy — keep a lot of Aspen’s lights on every day.

“In 2015 we reached 100 percent renewable powering our electric utility. It took 10 years,” said Aspen Mayor Steve Skadron. “Getting the last 25 percent was a huge challenge for us.”

Today more than 30 cities across the United States have pledged to find a path toward 100 percent renewable energy. Many more are mulling their own goals after President Donald Trump announced plans to pull out from the Paris climate agreement. Whole states want to get into the mix, too. California could set a 100 percent renewable energy goal if the state legislature passes a proposal now being debated. Two Democrats in the race to be Colorado’s next governor, Mike Johnston and Jared Polis, have said they want the Centennial state to pursue similar action.

How might the pieces of the puzzle come together?

Aspen set the 100 percent renewable goal in 2006 as part of its Canary Initiative, a climate action plan aimed at reducing the city’s carbon footprint 30 percent by 2020. But the story goes all the way back to the 1980s, when the city built the Maroon Creek and Ruedi hydroelectric plants.

Aspen’s municipal utility promoted energy efficiency with residents through voluntary programs and home energy audits. It mapped out a course to reach the 100 percent goal by making power purchase agreements, and hatched plans to build a third hydroelectric power plant, the Castle Creek Energy Center.

In a land of seemingly limitless resources like Aspen, where the median home sales price is $750,000, the fight over the Castle Creek Energy Center stands out. Between 2007 and 2012, the city spent $7 million on legal fees, studies, equipment and a custom turbine and generator. Several environmental groups opposed the measure out of concern for aquatic life and low river flows. Other groups supported the plan. But Aspen voters decided narrowly to nix the project in 2012.

Today Aspen still owns a $1.4 million hydropower turbine and generator. Dave Hornbacher, director of Aspen’s utilities and environmental initiatives, is in charge of finding a willing buyer or project to use the equipment. The city won’t disclose its location.

“Let’s just say it’s here in Aspen. It’s close by,” Hornbacher said.

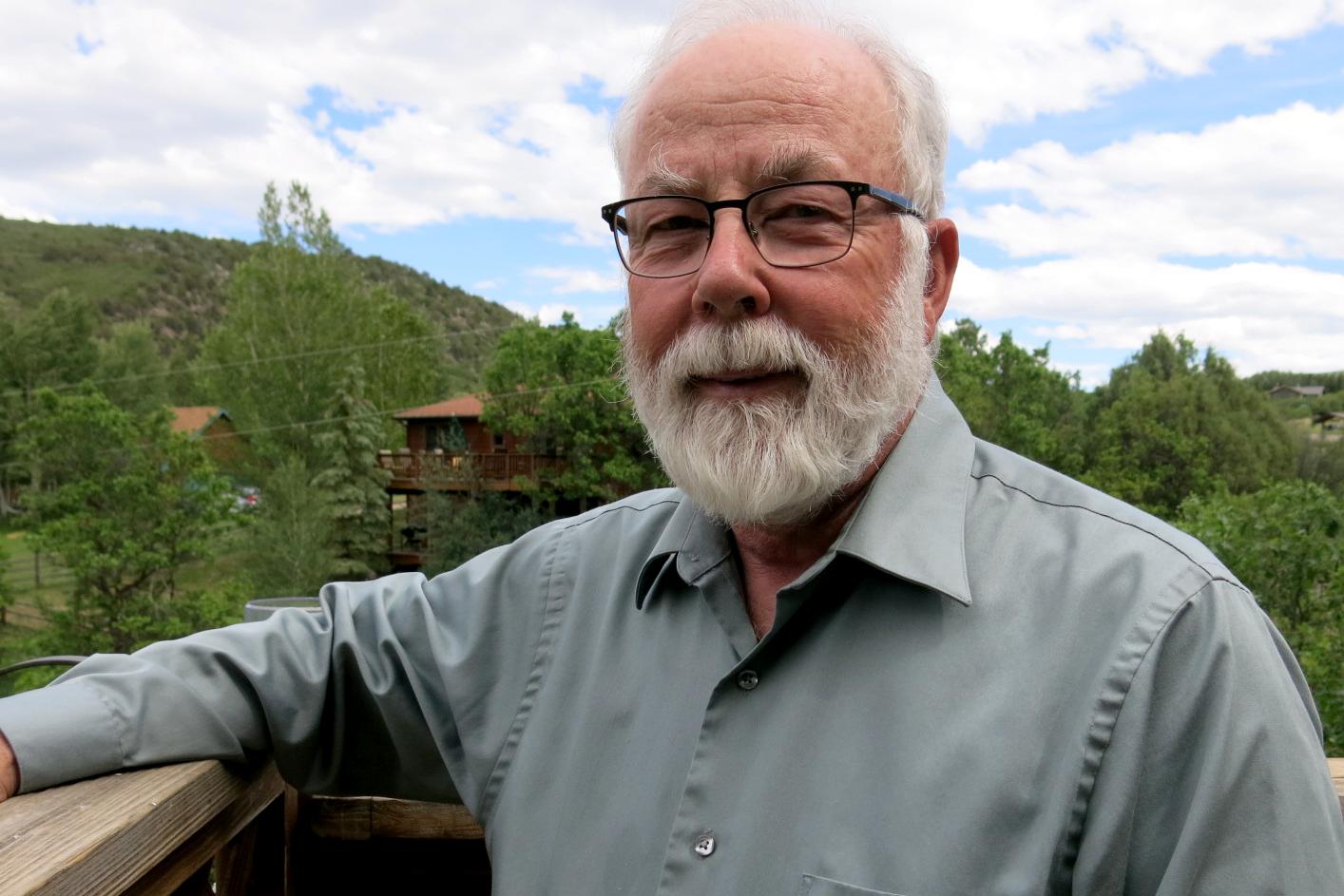

Ken Neubecker, an environmentalist who opposed the Castle Creek Energy Center, said there’s a lesson in all this for other cities on the road to 100 percent renewable energy. By his estimate, Aspen got too invested in the specific project early on. He said it wasn’t able to change course when it became clear the plan didn’t address environmental concerns.

“You’ve got to go to the community upfront and say, ‘This is what we want to do. How do you think we might get there?’” said Neubecker. “Be open to new ideas and new ways of thinking. That’s what Aspen didn’t do.”

There’s an argument that Aspen was up-front about plans. In 2007 it asked voters for more than $5 million in bonds to build the hydroelectric center. Voters overwhelmingly approved the idea back then, before eventually nixing plans.

Power Purchase Agreements Prove Key

Ultimately Aspen got its electric utility to 100 percent renewable energy through the use of power purchase agreements. Hornbacher said signing agreements can lock in low prices for decades. There’s also a benefit for companies seeking to build projects. At Ridgeway Reservoir, an Agreement with Aspen to buy electricity for 20 years helped the project’s owner, Tri County Water Conservation District, secure loans.

Nearby Aspen Skiing Company spent many of the same years working in tandem on its environmental goals. While Aspen Skiing Company gets power from another utility Holy Cross Energy, the company cut its carbon footprint by incorporating more renewable energy. Aspen Skiing Company also built a power plant to convert coal-mine methane into natural gas.

Today, only about half of Aspen residents technically get electricity that’s 100 percent renewable energy. That’s because Aspen’s municipal utility only supplies power to half of residents. The other half get power from Holy Cross Energy, whose power mix is about 30 percent renewable energy. Overall, the energy mix now comes from 53 percent wind, 46 percent hydropower and 1 percent landfill gas.

Outside Aspen, two other Colorado cities have declared 100 percent renewable goals: Boulder and Pueblo. While Aspen was driven by its own environmental goals, Pueblo and Boulder have received guidance from the Sierra Club’s Ready for 100 Campaign.

“Cities represent typically a large percentage of a utility’s energy demand,” said Jodie Van Horn, director of the Sierra Club campaign.

Just like Google uses its buying power to ramp up its clean energy use, Van Horn said cities from Atlanta to San Diego have their own economic might. But every path will look unique.

One of the easiest roads unfolds for cities, including Aspen, that own and manage their own utility. This arrangement lends maximum flexibility. Others, like Pueblo, have more complicated arrangements with their investor-owned utility Black Hills Energy that could take time to negotiate. Boulder is attempting to form its own municipal utility by breaking away from Xcel Energy, an effort that’s proved costly and time consuming.

"Cities have to take into account both the resources that are available to them — how much wind or how much solar is readily available in their area — but also the policy and regulatory frameworks in which they’re operating," she said.

The Sierra Club said most cities pair 100 percent renewable energy goals with climate action plans. A recent report estimates that the 36 cities that have already reached their goals, or have made commitments could collectively reduce carbon dioxide emissions by more than 19 million metric tons per year.

Across the country there is a more broad push to move states, and even the country, on a path to 100 percent renewable energy. But the question about how — or if — the country can get there is very open.

One concern as more cities decide to chart their own course is that they’re not coordinating closely with states and regional grid systems to think about the cheapest and most cost effective ways to deliver renewable power.

"Cities doing it on their own, states doing it on their own, will make it harder to solve our climate goals,” said Christopher Clack, who leads the Colorado-based modeling firm Vibrant Clean Energy.

What exactly the country’s mix of renewables can, and should, look like in 30 years is a source of great interest and debate. Clack and 20 other researchers initiated a lively debate when their study challenged an influential 2015 report that estimated the U.S. could reach 100 percent renewable energy with just wind, water and solar energy.

"What we're trying to say is that 100 percent renewable with a wind-,water- and sun-only scenario is actually one that makes it a lot harder and a lot more expensive,” Clack said.

On a national scale, Clack said a big challenge stems from how people get power when the sun isn't shining or the wind isn't blowing. The cheapest way to deliver reliable energy may come from small amounts of nuclear and natural gas burning if emissions can be stored deep underground.

The 2015 report’s main author Mark Jacobson has said the rebuttal was influenced by “allegiance to energy technologies that the 2015 paper excluded.”

These questions aren't weighing on Aspen Mayor Steve Skadron. He's thinking about a new course for his city after reaching the 100 percent renewable goal.

"I had a gondola conversation with a gentleman in the winter who said you got to 100 percent, now you have to go to 150 percent,” Skadron said, before pausing with a sigh at the idea.

With thousands of commuters driving into Aspen every day for work, the streets are getting more crowded. Emissions are adding up. Skadron wants the city to be more accommodating to electric vehicles while reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

"We have some really ambitious goals around mobility that speak to environmental priorities. I think that's going to be next for us."

Skadron said an electric vehicle readiness plan will help with that plan. He has the ear of top executives at major companies including Tesla. The hope is for new technologies and innovation to re-shape transportation in the city.

The larger challenge for Aspen may lie with its 2020 Greenhouse Gas reduction target of 30 percent. Thus far, the city reduced emissions 7.5 percent, and has further to go. Transportation, airport emissions and the natural gas used by city of Aspen municipal utility are significant sources of emissions.

Workers with the Canary Initiative anticipate charting a new plan with more specific steps later in the fall.

Editor's note: Owing to an editor's error, power purchase agreements were misstated in an earlier version of this story.