Denver photographer Lewis Mitchell Neeff wants to change the way you look at portraits. He's done so by diving deeper into the lives of his subjects.

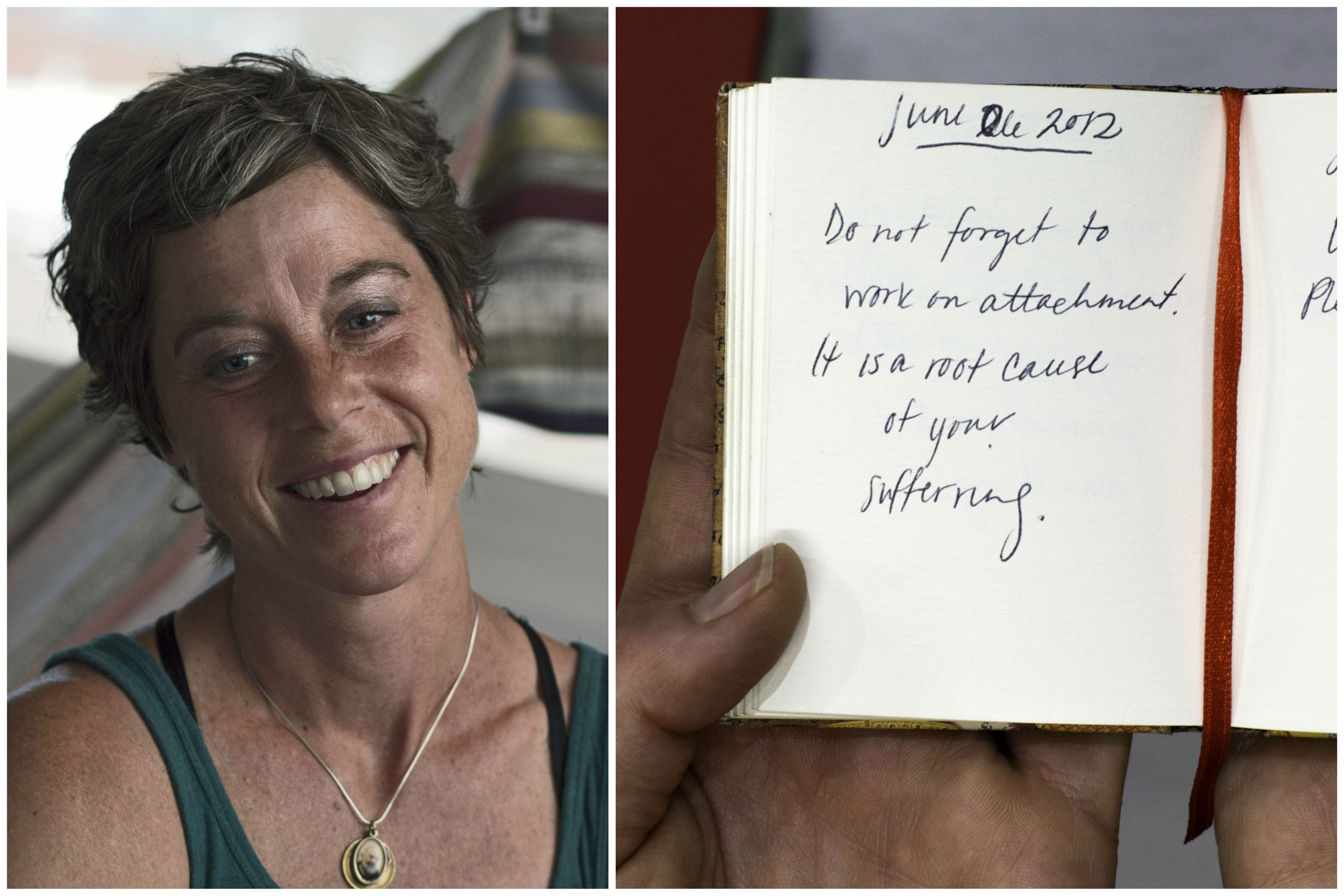

Take Tonia Crosby, an Evergreen, Colorado resident who's overcome two bouts with cancer. Her battle is shared as part of Neeff's exhibition "Vulnerable," which runs at Denver’s Dateline gallery through Aug. 20.

In the show, you'll find a small diary she kept after her first diagnosis that’s full of short inscriptions like this:

"July 3, 2012: Pain, like pleasure is a message. It is not a punishment. Be with it."

Crosby wrote that entry after her breast cancer had spread. The constant pain, she says, was unbearable. Even more, Crosby was an athlete and practiced yoga, so the disease drastically changed her routine.

"To have physical pain take me out of the game like that, that was the hard part for me," Crosby says "It really sidelined me."

After surgeries and radiation, Crosby decided to try Eastern medicine. As part of the treatments, a Tibetan physician encouraged her to pray and meditate. She created an altar in her home, where she sat with her thoughts — some of which she wrote down.

Crosby recently happened across that small diary, and thought twice about putting it on public display at Dateline. Re-reading one of the pages initially gave her pause, but “that’s what made me decide that I should hand it over. I figured, that’s vulnerable isn’t it?"

Crosby’s second bout with cancer was a stage four diagnosis. Doctors said it was terminal, but she kept fighting. Something miraculous happened in May, she says, and she's been getting better ever since. That’s why Crosby answered Lewis Mitchell Neeff’s call for stories of struggle and triumph.

Next to Neeff’s studio in Denver’s Temple artist haven sits a big, wooden photobooth that he built four years ago. It even has a name: Oz Box.

Neeff says the Oz Box experience is "like the man behind the curtain," because early on most of his subjects didn't know he was hidden away in a secret compartment behind the camera. Before Neeff had a permanent studio, the Oz Box was his makeshift one. He'd set up the mobile booth at different events. It’s how he made a living and built his reputation.

"I think it was huge," he says. "It created a space for me to break down what I thought a portrait was and see all of these candid moments unfolding."

Neeff used to slip notes to unsuspecting subjects in the booth and snap photos as soon as they reacted. The booth allowed people to be themselves, which is what Neeff wanted as a portrait photographer.

"Being able to capture moments of what is unique to that person's individual requires a moment of vulnerability," he says.

His decision to take that idea even further is how he connected with Tonia Crosby and seven other subjects. Neeff met with them, listened to their stories, and then took their portrait.

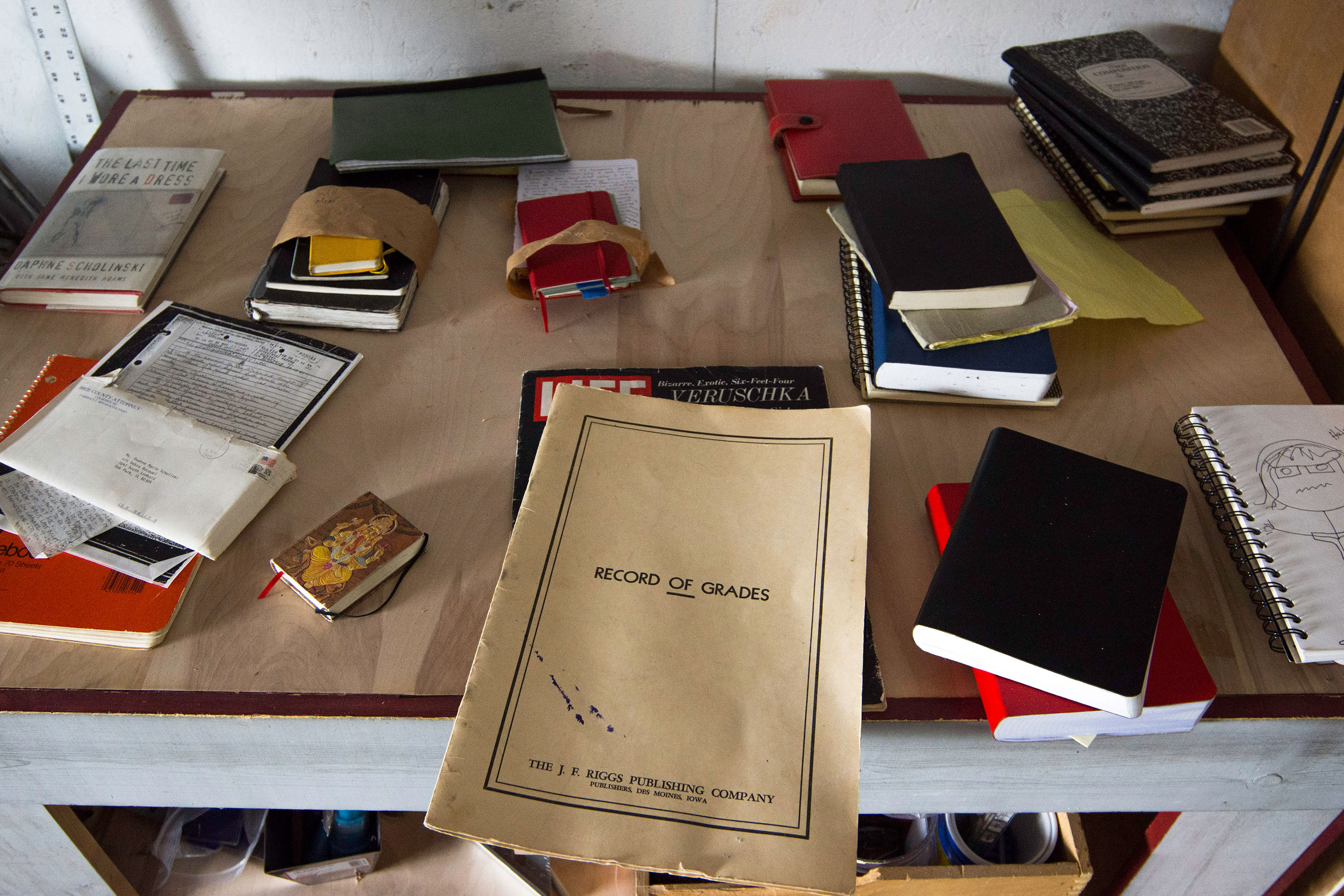

He also asked them to hand over something that documented their journey. These intimate materials, diaries, sketchbooks and other records are part of the impact of the portrait exhibition. One journal reflects on a recent move to New York City. Another, titled "Feeling Analysis" from 1982, comes from a transgender portrait subject who Neeff says was institutionalized.

What was it like to ask people to share this stuff?

"It was incredibly humbling,” Neeff answers. “It's a big ask. But I do think it's important, and I think it's important that I approach it gently."

The project is now evolving. Next, Neeff will work with a Denver group called Arthyve to create a diary library that would archive journals for people to read. It’s his hope that it would offer a deeper understanding of what it is to be human, much deeper than any 2D image can go.