On the third floor of the Pueblo County Jail, Detention Bureau Chief Jeffrey Teschner leads the way to a small cell in a wing for women.

The room is meant for a single inmate. In Pueblo, almost all of the cells like it hold three people. Two women bunk against a wall. The third is said to “roll on a boat,” meaning she sleeps on the floor on a blue plastic cot.

“This is the standard,” Teschner says. “This is the triple bunking right here.”

One inmate agrees to talk about her life inside the cell. “It’s claustrophobic,” says Savannah Sandoval. “You feel smothered.”

More blue cots line the open area at the center of the cell block. Inmates often end up here as they ride out withdrawals, says Cricket Dordy, another inmate and a self-proclaimed heroin addict. She says she has some first-hand experience.

“If you’re out here they put you out here because you get sick,” she says. “You get nausea. You get diarrhea. Because it’s quicker for you to go to the bathroom.”

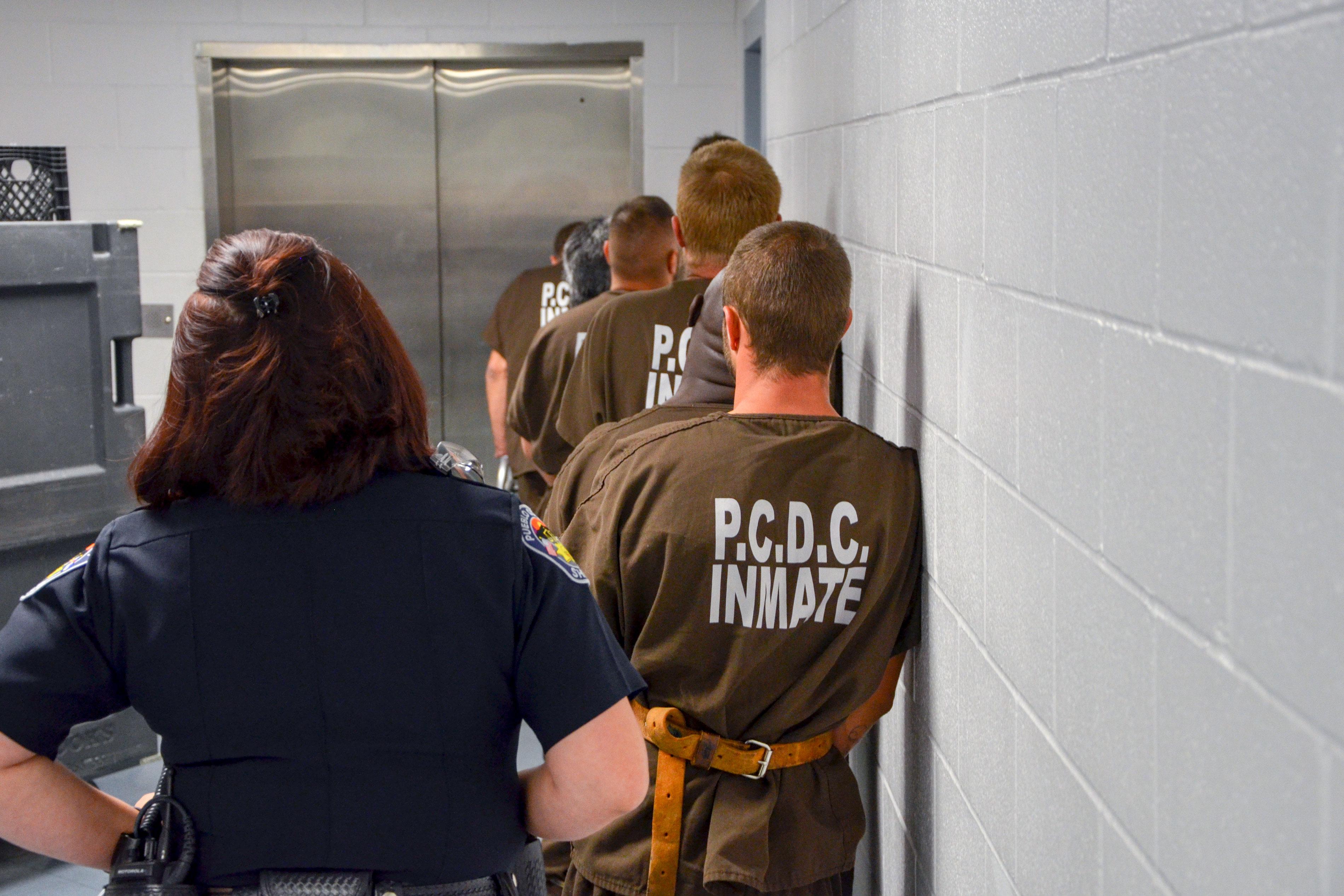

A recent report found the Pueblo County Jail operates at an average of 145 percent of its intended capacity. It’s the most extreme example of a statewide issue. A survey of 20 Colorado county jails identified seven as overcrowded.

To understand the reason behind the problem, a good person to start with is Pueblo County Sheriff Kirk Taylor. He explains the situation as a riddle. Bookings into the jail have been more or less static over two decades. What has gone up is the time people spend in the facility, which he says has now reached 38 days.

Sheriff Taylor points out a few reasons particular to Pueblo. The local district attorney has stepped up prosecutions of certain crimes. Pueblo County also has a high rate of opioid use and drug-addicted inmates tend to stay in the jail longer.

But Taylor traces many of causes to the State Capitol in Denver. With a degree of pride, Taylor takes out a binder the size of a phone book. It holds all the legislative changes he thinks have packed more people into the jail.

“There are numerous statutory changes that have culminated in exactly what you are seeing. Three empty prisons. County jails are full,” he says.

Taylor has examples at the ready. A few laws have reclassified certain drug felonies as misdemeanors, which can be served in county jails. Parole violations often now result in a jail stay instead of a return to state custody.

Over the last few months, state lawmakers have been looking into jail overcrowding and funding for county justice systems. The interim committee is now considering solutions. It will vote on a set of five bills to recommend in October.

Meanwhile, Pueblo County is going to the voters this November for a county-wide sales tax increase of 0.45 cents to build a new jail. Part of the existing facility would be refurbished into space for detox and addiction treatment.

“We need to take control of this situation before we are having to react to it,” says Commissioner Garrison Ortiz, who is leading the campaign for the ballot initiative.

Ortiz sees the jail as a financial time bomb. Not only do the conditions put inmates and staff into routine danger. The cost to repair the aging facility keeps going up.

For proof of the deterioration, county officials offer a piece of surveillance tape. It shows bats flying around the inside of the building. The critters make it in through cracks in the exterior of the vintage-1980 jail tower. “Every month we have an exterminator come and look for bat nests,” sighs Detention Bureau Chief Teschner.

The jail also presents a legal liability to the county, according to Commissioner Ortiz. Civil rights groups in Nebraska and New York have sued counties over conditions in overcrowded jails. If the same happened in Pueblo, he fears the county could no longer address the problem on its own terms.

Sheriff Taylor agrees conditions inside the jail have reached a legal breaking point.

“If we don’t get to where we need to be as a community soon, I anticipate a large lawsuit. And unfortunately, I’ll be their best witness.”

Mark Silverstein, the legal director the ACLU of Colorado, could be the one who calls Taylor to the stand. He is no fan of the current plan to address the jail in Pueblo. For him, building an expanded facility is “absolutely the wrong answer and the wrong solution.”

His preferred approach would be to see the county address the detention of pretrial inmates with outstanding bonds. If people could afford to leave as they await trial, they would stop overburdening Colorado sheriffs, says Silverstein.

The move has some precedent. Over the last year, New Jersey has all but eliminated cash bonds in favor of a risk assessment tool. The result has been a 30 percent reduction in the jail population as of July. Crime is also down for the year.

Sheriff Taylor thinks such programs are part of the solution, but not all of it. Pueblo has one of the few pretrial services programs in the state. The system works to determine if someone accused of a crime presents a risk to the public. If they don’t, they can be released to await trial. Taylor is unsure if judges currently have confidence in the system. He also thinks pretrial services should be primarily used to insure public safety — not to reduce the population of the jail.

Still, discussion of pretrial inmates goes to what Sheriff Taylor sees as the most important thing to understand about jails. Unlike prisons, not everyone is there to be punished.

“If you believe in our form of justice, then 75 percent of people in this building are innocent because they have not been proven guilty yet. I mean think about that,” he says.

It’s a lesson Taylor hopes lawmakers keep in mind this winter as they consider ideas from the interim committee on jail overcrowding.