What do you do with expired prescription drugs?

Most people who abuse prescription painkillers get them from a friend or relative for free, according to research published in the JAMA Internal Medicine journal. Health and safety officials want to change that.

Saturday marks National Prescription Drug Take Back Day, and Colorado is in the process of ramping up with more than 100 permanent drop boxes in at least 43 counties, including at police agencies, pharmacies and health providers.

“Home medicine cabinets are really a significant source of prescription drugs that are abused nationwide, and in here in Colorado,” said Greg Fabisiak, the state’s program coordinator. “Statistics show that teens are well aware that medicine cabinets contain drugs that people no longer use or might have forgotten.”

CPR News asked our Facebook and Twitter followers about how they deal with their leftover prescriptions and the results were all over the map.

We're curious, what do you do with expired prescription drugs?

Many said they set medications aside for Drug Take Back Day. “Just had to dispose of my husband's UNused, UNopened, still sealed, prescriptions,” said Dana Jensen of Denver. “Sad there is not some way these could be legitimately used by someone else. What a waste! And some can't be dropped off — expensive inhalers for example.”

Many seemed to be aware that some pharmacies and health providers collect unwanted prescription meds. Lara Velarde pointed out that “Kaiser has drug drop off bins and places like Safeway have mail-in bags.”

“My city (Broomfield) has a drug drop off box at the police department,” said Kerry Pettis. “A great public service, in my opinion.”

Others said they did get rid of unused prescription drugs, but not at a drop box. “Chuck them in the trash,” posted Proteus Duxbury of Highlands Ranch. Wanda Emerson said she did the same, mixing them “with things like coffee grounds, etc.”

It might come as a surprise to the last two commenters, but trash cans aren’t recommended. Even mixing meds with kitty litter or coffee grounds won’t necessarily prevent drug theft, since they can still be retrieved and misused or sold illegally, according to the state of Washington. That state’s Take Back Your Meds site also notes that crushing pills and then tossing them in the trash is not a good idea, since it risks exposure to the drug via breathing in the dust or skin contact.

A third option is also frowned upon: Flushing them down the toilet can pollute water supplies, damage aquatic species and contaminate both water and food.

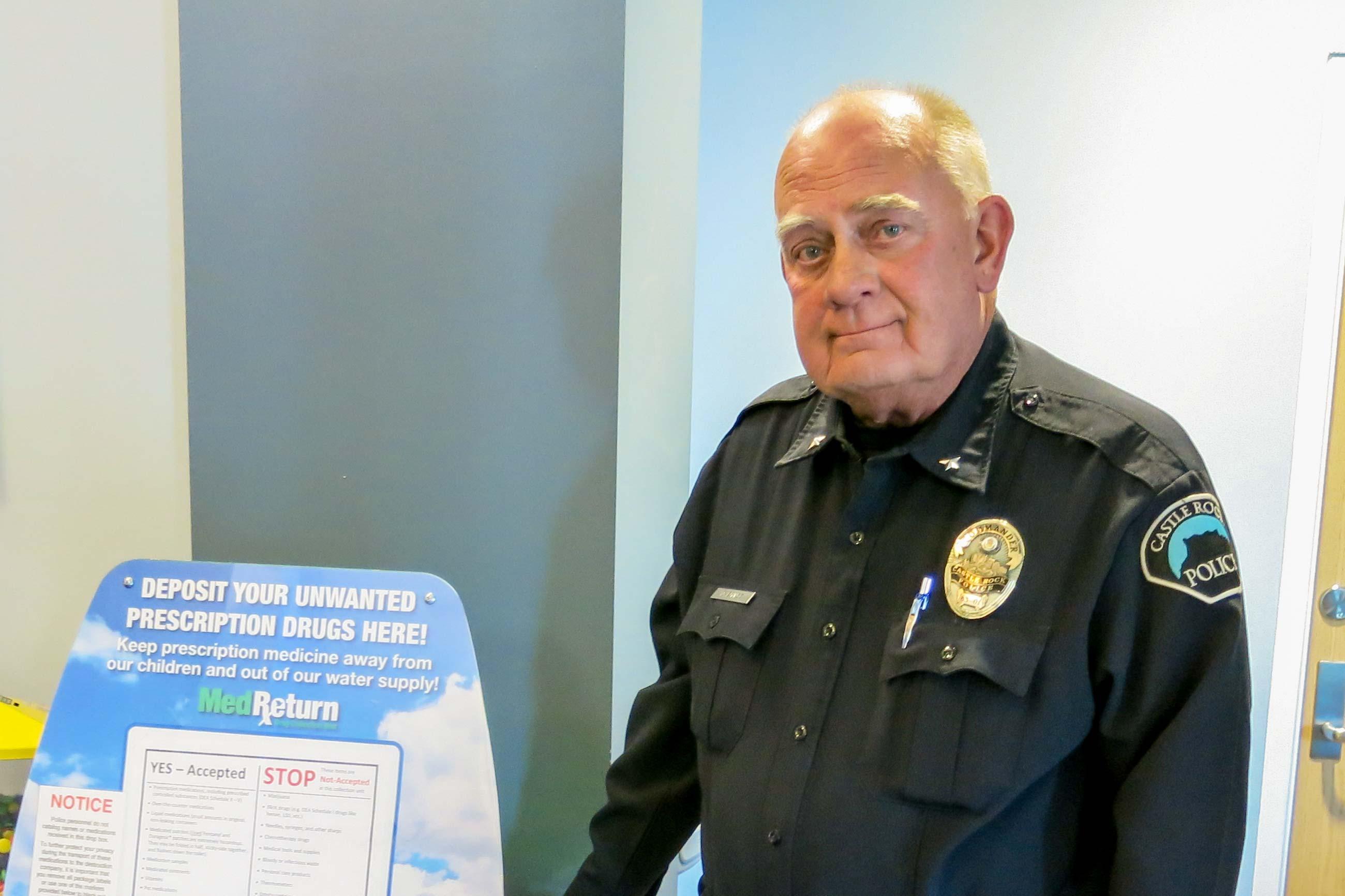

Many Colorado counties have drop off boxes for prescription drugs like the one in the lobby of the police department in downtown Castle Rock. There, you’ll find a locked green metal box that reads MedReturn Drug Collection Unit. One thing to remember when you drop off prescriptions, said commander Doug Ernst, is that residents should remove their name off the label, blacking it out with a magic market.

“They go ahead and mark off their name and whatever other information, they just go ahead and open the door, put the medication in there and let the door slam and that's a done deal,” Ernst said.

There’s also a very Colorado twist: A sign stated the box cannot be used to dispose of marijuana, or illegal drugs.

Ernst said residents drop off about 30 pounds of prescription meds a week, more than 1,200 pounds a year. The police commander couldn’t be happier with the results of the drop off.

“It takes the wrong medication out of the wrong people's hands,” Ernst said.

Robert Valuck, of the Colorado Consortium for Prescription Drug Abuse Prevention, cited the research from JAMA on people who abuse opioid pain relievers first getting them from the medicine cabinet of a friend or relative when it comes to where they can make an impact.

“We think this is the lowest of the low-hanging fruit. Just clean out the medicine cabinets,” Valuck said. Or he said, install a lock box in your home.

Mother-turned-activist Karen Hill, of Aurora, and her family learned that lesson in the hardest way possible. Five years ago, she lost her son J.P. Carroll at age 26. “It was a complete shock, I mean we had no idea that this was even an epidemic at the time,” Hill said. “So when we got the coroner report back we were 100 percent shocked.”

The coroner’s report found Klonopin in J.P.’s system. That was no surprise, as it was prescribed for him to deal with anxiety. But he often had a hard time sleeping. Hill said one night, on a family visit to his grandmother’s house, J.P. took one of her drugs from the medicine cabinet. There was a bad interaction and he never woke up.

“So it was very, very tragic,” Hill said.

She said in J.P.’s case, it was a very small dose of an opioid that caused the fatal drug interaction — and the prescription was perhaps five years old. “So it's just a real example of how easily these medications are for people to get completely unintended,” she said.

Hill, and others who’ve lost family members to an opioid overdose, are now on a mission to spread the word about the dangers. The loss of her son is the motivation behind a nonprofit, the JP Prescription Drug Awareness Foundation.

“I really don't think he had any idea that he would die from something like this,” Hill said. “And I think he would just be really frustrated that this took his life.”

Hill thinks time is of the essence. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioids, which includes prescription opioids, heroin and fentanyl, claimed more than 33,000 people in the U.S. in 2015, a record. It notes that nearly half of all opioid overdose deaths involve a prescription opioid.

In Colorado, a record 912 people died in 2016 from an overdose according to data from the state health department.