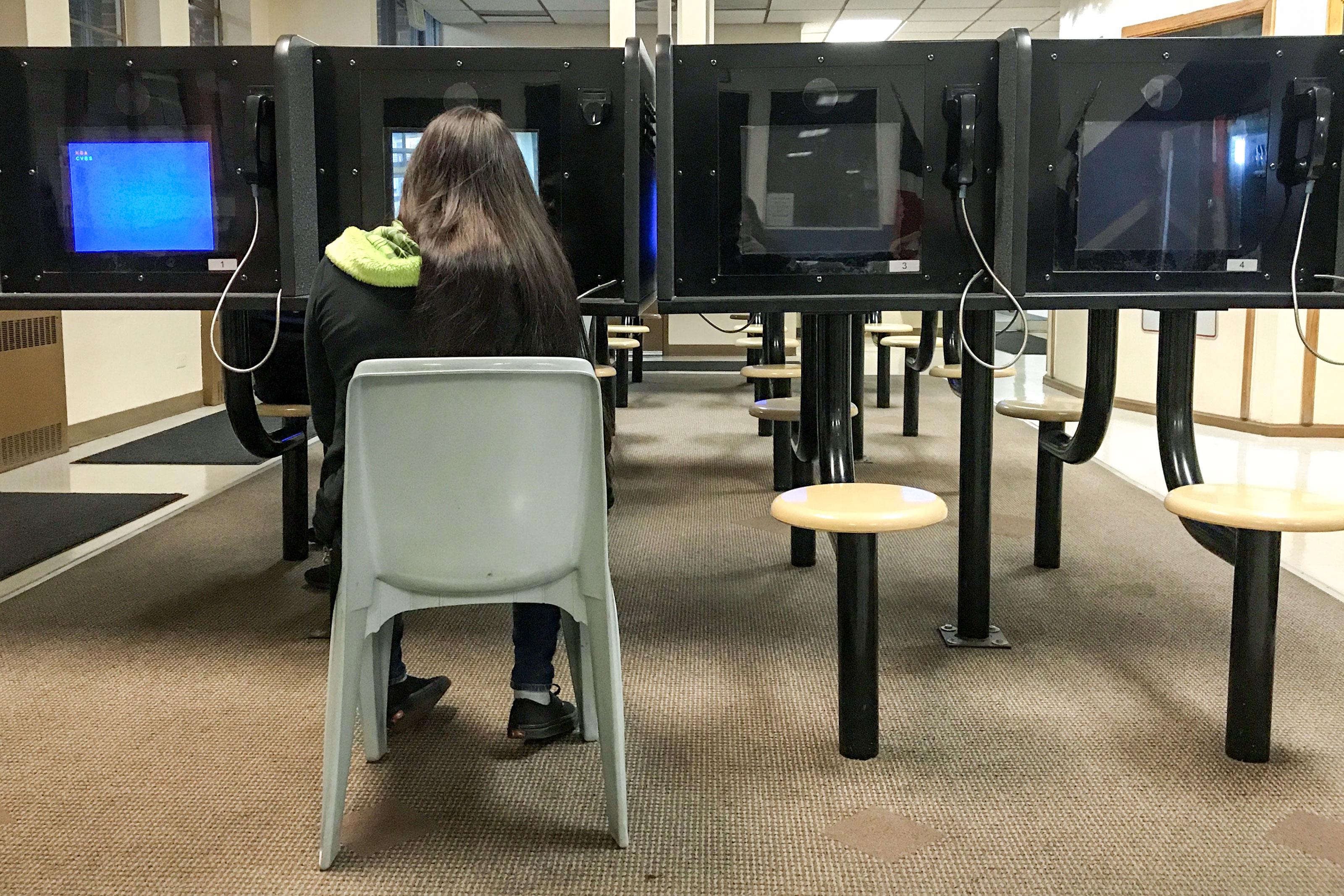

When visitors see inmates at Denver’s two city and county jails, they don’t meet loved ones across a table. Instead, they find rows of screens and telephone receivers.

Since 2005, video chat has been the only way to speak with inmates. Now there are efforts to change that, following a report from the city’s independent monitor that suggests the Denver Sheriff Department reinstate in-person visitation.

At the Denver County Jail near the East Denver Stapleton neighborhood, a woman waits for her son’s face to appear on one of the screens. To allow her to speak freely about her son’s situation, we’ve used a pseudonym — Janet — to keep her anonymous.

She says her 25-year-old son has been charged with first degree murder, and he’s been held for six months already.

“He is having an emotional breakdown right now because he can't wait to give me a hug,” Janet says. “So he wants to plead guilty because he wants to go to prison so that he can give me a hug again.”

Janet doesn’t want her son to plead guilty, but the isolation has been terrible for his mental health. He doesn’t have a cellmate at the moment. She says he’s tried to take his own life multiple times. If he pleads guilty, and is sentenced and imprisoned, he’d eventually have the opportunity for in-person visits.

“Can you imagine being in a cell all by yourself, and only being out for a couple of hours everyday?” Janet asks. “I mean, I couldn’t handle it. Could you?”

Janet’s son is innocent, at least in the eyes of the law until proven otherwise. He’s at Denver County Jail awaiting his day in court. Most of the population here is made up of pre-trial inmates. That’s one of the issues Nick Mitchell, who oversees Denver’s Office of the Independent Monitor, has with the video-only visitation policy at the jails.

“We shouldn't be punishing people who are innocent until proven guilty unnecessarily,” Mitchell says.

The policy applies to all the inmates, including some who are serving years. Mitchell says that “depriving inmates of of in-person visit simply isn't humane.” For those who are parents, their only contact with their children has been over a video screen.

“It has particular impacts on children of incarcerated parents,” he says. “And it was my view that we need to do whatever we can to minimize the trauma associated with incarceration on innocent family members and on innocent children.”

In the October report, Mitchell cites multiple studies that show the positive impacts of in-person visitation. The results of one study says they can help decrease the chance of an inmate committing another crime, by up to 30 percent.

“I think we're just not taking advantage of those opportunities to try and improve behavior while inmates are inside, and reduce recidivism through in-person visitation,” Mitchell says.

The Denver Sheriff is in agreement with the monitor. In response, jail division chief Elias Diggins has put together a 35-person working group to explore the feasibility. Their first meeting will occur in early December. There’s currently no timeline for any policy changes.

“Jails are now understanding why in-person contact visitations are so important to the folks that are in our custody, as well as their families and friends,” Diggins says. “Ensuring that they stay connected, and that they have folks that they can lean on when they're released.”

The policy of the American Correctional Association, which chief Diggins is a member of, says video shouldn’t be the only visitation option. Diggins agrees, but there’s an issue.

In 2005, when construction started on the Van Cise-Simonet Detention Center downtown, Diggins says the mindset was video-visitation only. At the time of its dedication, it was hailed as a “national model for an improved justice system.” There were issues with domestic violence, and contraband being snuck in, so the jail wasn’t built with in-person meeting spaces. Today, “it would be very expensive and very difficult to change,” Diggins says.

Democratic State Rep. Leslie Herod says that was an oversight, and she’s considering creating state legislation in response so that we’re not “creating more jails that don’t have the capabilities for in-person visitation.” Adding that, “because of that faulty design, we now have to go back to create new solutions that will cost money.”

At the county jail in East Denver, Diggins says there’s more space flexibility. It’s also where people serve longer sentences, and he thinks it’s more important for those people to have the chance for in-person visits.

Because of the physical constraints, Diggins says it’s a priority to update their more than 10-year-old video technology. The city is moving ahead with a $1.4 million-dollar contract to do exactly that. It would allow loved ones to video chat inmates from home — for a fee. It would also connect the East Denver and downtown jails, so visitors could choose whichever is closest to them.

Janet says getting to the jail isn’t the hard part; it’s only being allowed to see her son on a screen.

“I mean, to be able to hug [my son] again is just beyond belief,” Janet says. “There is not a day that did not go by that he did not give me a hug and a kiss. That was totally ripped away from me.”