Change is underway at a network of Colorado Springs schools looking to break away from the traditional model for teaching. Each of these Next Generation Learning schools redesigned themselves to create more relevant, authentic learning experiences.

It’s been a radical shift from the traditional mold that created teachers who were “so worried about a test score … that we created almost robots that were afraid to create or innovate,” said Scott Fuller, the Next Generation Learning coordinator for Colorado Springs School District 11.

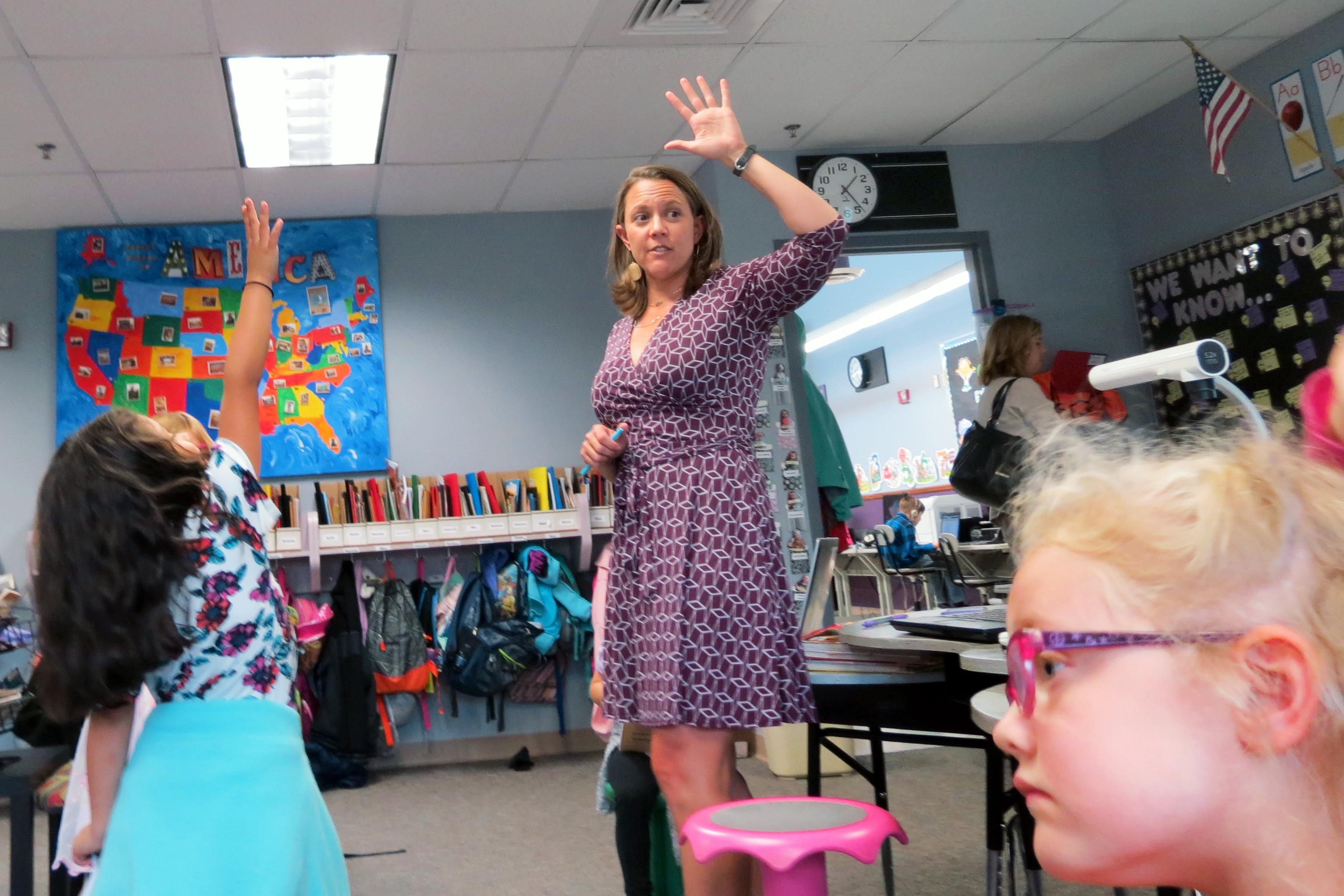

Take Trailblazer Elementary on the far northwest side of Colorado Springs. Several years ago the classrooms had kids sitting in rows. And teacher Alycia Eschler was like all the other teachers, telling the kids “exactly what we were going to do and how we were going to do it and how they would show mastery.”

Now, the school is striving to live up to its name and things are different for Eschler.

“I provide curriculum for them and standards but they’re choosing how they want to learn it and how they’re going to show me that they’ve learned it.”

Here’s how it works: At the beginning of each math class, students have to figure out four math problems written on the board. They then check in with the teacher. Third-grader Paige Pakenham likes how the school “gives us choices, multiple choices.”

Based on their answers students rotate through different stations: math activity cards, collaborative group work, or computer programs that let you advance at your own pace. It’s all very fluid and kids oversee what they’re doing.

“I like how the teachers aren’t always telling us what to do, so we sometimes figure out what we have to do on our own,” said student Nathaniel Wojcik.

Each kid carries around a folder with learning targets they’ve helped set. Teachers are in the background for kids who need to check in for help. There’s a rule: if you get stuck, you go to three fellow students before asking the teacher.

It’s a similar situation in other classes and subjects. In Mackenzie Meyer’s reading class, there’s a bell that lets kids know it’s time to rotate.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Meyer’s calls out. “[The] collaboration [table], if you did not finish it goes in your reading folder and you’ll head to tech, tech [table] you can log out it will save your place, head on over to the kidney table to work together.”

It’s not quiet and controlled, there’s lots of classroom action. Teachers say the furor means that students are learning. In the highest functioning classrooms, said coordinator Scott Fuller, the teacher is often hard to find. Sometimes it can take students awhile to get into the task before them. There can be a tiny bit of minor squabbling at one table, but remember, the students helped set their own goals and eventually they get the job done.

This big shift from the teacher deciding the direction of everything to students learning on their own had teacher Mackenzie Meyers “scared beyond all belief.”

It was overwhelming, especially for a self-described “control freak” like her. She also came from a district where half her evaluation depended on whether students hit the mark on test scores. Now, she just tells kids what the standards require.

“The kids keep that in the back of their mind and they have it in their notebooks and they know that these lessons or centers are all giving them a way to access that and they just have to choose which way it works for them, so I’ve seen it work,” she said.

Her science students last year “knocked it out of the park” in terms of how well they did on tests. But what is more important to her is, now, instead of half or two-thirds of kids engaged with the material, is that “95 percent of my students on any given day are focused.”

By ceding control, teachers have found “the kids will help you take it two steps further,” said library technology educator Nicole Ottmer.

As part of the Next Generation schools network, the staff at Trailblazer Elementary also made other significant changes in how children learn, which are being analyzed by several education think tanks. Each class has multiple grades. Special education students aren’t shuttled off to a separate room; they get support within the regular classroom.

Students even have a voice in some of the operational decisions like helping redesign the library and sitting in on teacher hiring.

Developing an entirely new model “has not been a walk in the park,” said teacher Kaylee Vasquez.

“We’ve gone into Ms. Rubio-Gurnett’s (the principal) office, guns blazing, mad and she’s like ‘what do you need next? Is it a day off to go look at somebody else’s classroom? Is it a day to spend with your team and talk and collaborate and work through the frustrations? Do I need to bring somebody in to facilitate a design thinking process with you?’”

Trailblazer’s approach to learning acknowledges that students need to think for themselves, not regurgitate academic content. There is a disconnect, though. The state says civic, personal, professional and entrepreneurial skills are equally as important as academic skills. But schools are graded on how students do on the state tests. Principal Denise Rubio-Gurnett pointed to a survey where no parents talked about wanting their kids to score high on tests.

“They said, ‘you know what, I want my child making a difference for the world. I want my child to have a global awareness for why they should leave a smaller footprint. I want my child to be a leader of themselves and others and be respectful.’ They came up with this mission for us that was much bigger than we originally could even articulate,” she said.

Trailblazer decided that state test scores were no longer going to define them. So far, whole-school approaches to more personalized learning are showing modest academic gains. But here’s the more important point: tests can’t reflect everything these kids are learning. Next Generation Learning coordinator Scott Fuller said the school is experimenting with new assessments.

“If kids can actually talk about what [they’re] learning, if you can pull up hard evidence in a portfolio and see what that looks like, most parents will say, ‘I can see exactly where my child is. My child can articulate where they are and where they're trying to get to. Then grades became less important. Those standardized test scores become less important,” Fuller said.

Parents know that grades and tests scores are part of the system students use to move on after high school, Fuller said, but that system is changing. Mostly because future employers don’t equate that with success anymore.

“Colleges are starting to shift what they equate with success and moving more towards ‘prove it to me. Prove to me you know that. Portfolios interviews what have you done with this to apply it,’” Fuller said.

At Trailblazer, learning how to apply knowledge means letting kids struggle for a while, figuring out how to find an answer on their own. During the popular “Genius Hour,” first-grader Fox Gheen gets to investigate his own research question on where computers from and how are they powered.

Fox is writing a letter to computer expert. But he doesn’t yet know how to find that person, so he turns to teacher Kaylee Vasquez.

“I don’t know the answer to that,” Vasquez tells him. “Same as Cannon’s question. I have no idea even where to search for Cannon’s question.” (Fellow student Cannon’s question, by the way is, ‘Why does it feel weird when an airplane takes off – how do they fly?’)

Fox thinks about it for a while, then the lightbulb goes on.

“I know how I can get a computer expert! Can I go online?” he asks.

Vasquez gives him permission, but also sends a small curveball asking how he will start. The little boy ponders the question then proudly states “I’m going to type it in.”

“Start there and let me know how it goes,” Vasquez said. The learning process at Trailblazer continues in that fashion. Each student finds their own way or faces some directed questions from the teacher. If the smile on Fox Gheen’s face is any indication, the teaching model seems to be working.