While Vermont dairy farmers are experiencing some of the hardest times in recent memory, their counterparts in Quebec are thriving. The reason is a complex system that regulates the supply of milk and sets the price that farmers receive.

It's a short drive from Jacques Rainville's place in Highgate Center to Saint-Armand, Quebec. Along the way, Rainville, whose family came from Quebec, points out yet another farm gone fallow.

"Gone! No cows here," he says. "We've got another one on the corner here, beautiful farm, nice little family farm. No cows. It's sad to see it happen."

The Vermont Agency of Agriculture says 12 farms have gone out of businesses this year, bringing the number of working dairy farms down to around 750, compared to about 1,100 a decade ago.

Many farmers in Vermont say they're getting paid less than what it costs to produce the milk.

Like his father before him, Rainville farmed for over 30 years. He drives a milk truck for work now, but says he's still a farmer at heart.

We're visiting Canada with his cousin, Phil Parent, who has a dairy farm in nearby Enosburg, Vt.

As we approach the border with Quebec, Rainville says he thinks the Canadian system — which balances milk supply with consumer demand through production quotas — offers a valuable lesson for Vermont.

"The answer is managing our supply in this country to the demand of our people. Buyers react to oversupply because they know we have to get rid of it. And it's a downward spiral," Rainville says.

Just a few miles from the Morses Line border crossing, Hans Kaiser and his son milk about 95 cows in Saint-Armand.

A tall silo next to the barn bears the farm's name — Hepatica — for one of the first wildflowers of spring.

The senior Kaiser is tall; he wears overalls and rubber boots and has an accent that doesn't sound Quebecois. He came here from Switzerland in the 1970s.

In the barn's milk room are six people with strong ties to the land: The Kaisers, two other farmers from Quebec, plus Rainville and his cousin. Introductions happen in French and English.

The Canadians practically talk over one another as they explain and praise their system of supply management.

Hans Kaiser says when he came to Canada in 1975, he was able to establish a farm with his family.

"We always had this quota system," he says. "I believe we have the best system in the world. I have no doubt about this."

The quotas in Canada can be bought and sold; they're quite valuable, several million dollars or more for an average farm. The price that farmers are paid is also controlled: It's established based on the cost of producing milk on what's deemed to be an economically efficient farm.

The system is not financed by the government, although it has led to higher retail prices for milk than in the U.S. And even though the quotas are expensive, banks lend money to buy them. Quebec farmer Gerard Vermeulen says why wouldn't they lend?

"They know you're going to have that revenue. They're going to get paid," he says.

The farmers do a rough calculation to compare the price the Canadians receive with that paid to their Vermont counterparts.

It turns out the Quebec farmers are getting the equivalent of $24 for 100 pounds of milk, while a few miles over the border, Vermonter Phil Parent is paid about $14 a hundredweight from the cows he milks in Enosburg.

The math is sobering for Parent.

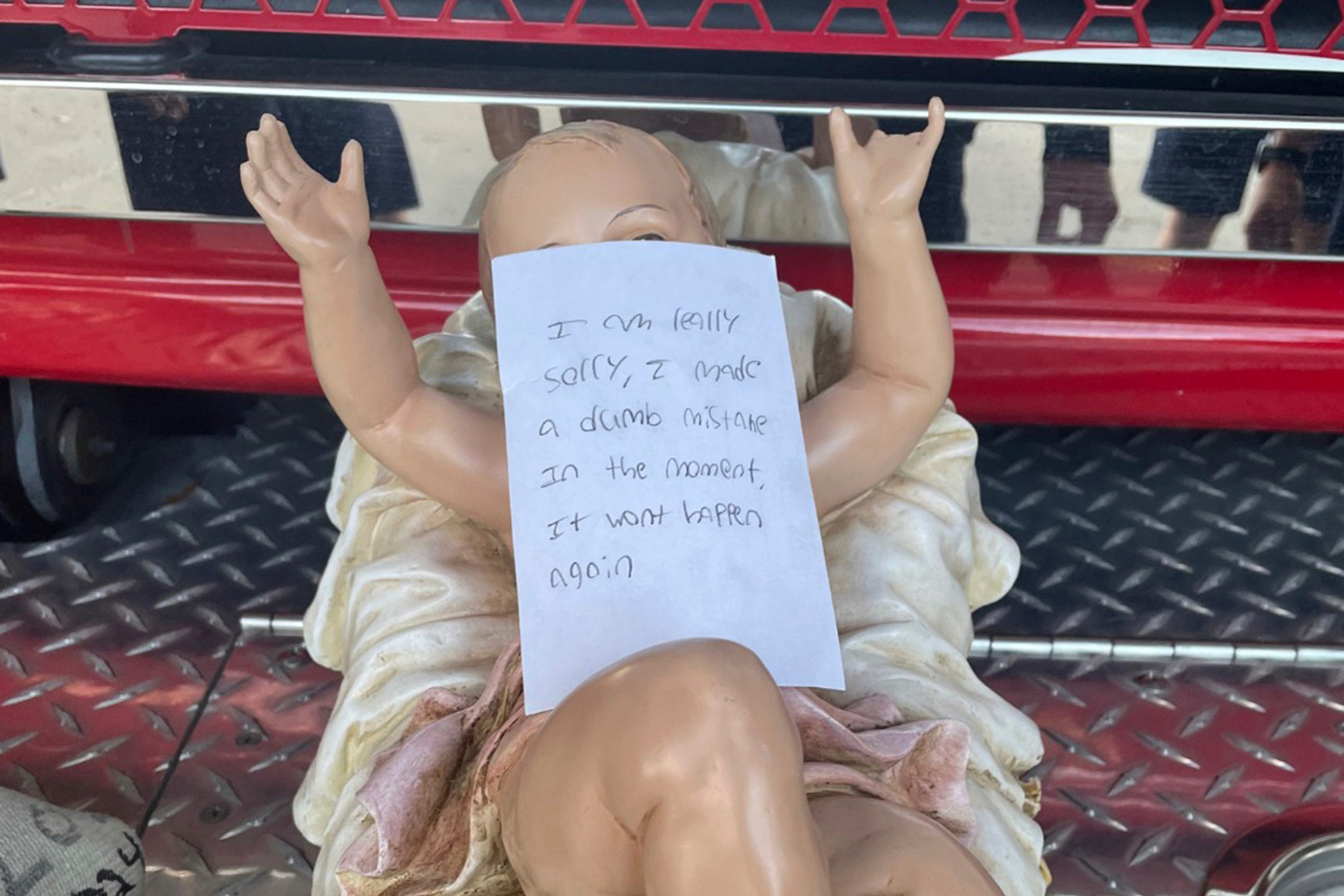

He says the Agri-Mark dairy co-op told him recently that milk prices were headed down in 2018. Included in the letter were numbers for a suicide hotline.

"So how do you feel when you see that? I was a little taken aback by that. I know they meant well, but there [were] four farmers in New York that killed themselves," he says. "They felt they had no recourse. Something's wrong with this industry, very wrong."

For Jacques Rainville, the crisis also hits close to home.

His son took over the farm several years ago when prices were high. He borrowed to buy a herd but couldn't cover his debts when the price plummeted. So he sold his cows to a startup dairy in Canada.

"I'm the one who ended up buying his herd," says Phillipe Swennen, who also farms in Saint-Armand.

Swennen is 39, and says supply management in Quebec allowed him to get a start in agriculture.

"We started from nothing," he says. "You can ask anybody in here. And today I bought two more farms. I'm up to 47 cows, I'm going to be up to 60 cows in next six months."

Dairy farming is a business that demands attention at least 12 hours a day, 365 days a year.

But these four Quebec farmers say they can balance their work so they get at least one day off a week, plus vacation.

Vermeulen says there's something else he notices about farms in Quebec.

"This is not nice what I'm going to say, but I think you people need to hear it," he says. "Go in Quebec, drive around the countryside, look at the farms. The tin is painted; the tractors are put away. There are a lot of nice farms in the States, I'm not saying they are all run down, but there's a lot more farms that are run down in the States than Canada."

As the conversation winds down, Hans Kaiser gives a tour of his barn where about 90 Holsteins lie on bedding or munch their midmorning meal.

The place is astonishingly clean. And Parent notes that it's about the same size as his farm in Vermont.

"Numbers-wise, we're very similar," he says. "But I hate saying it — my place isn't as immaculate as his place. We try to do what we can with what we have."

Parent would love to work under a supply management system like his fellow farmers in Quebec do. But that's proved politically impossible in the U.S., where the free market value is valued.

Nearly a decade ago, Vermont farmers led an unsuccessful effort to get a supply management system through Congress.

In the early 1980s, Roger Allbee was an aide to then-Vermont Rep. Jim Jeffords. Allbee, who later served as Vermont's secretary of agriculture, says Jeffords was very close to getting supply management into law.

But it was blocked by milk industry lobbyists, and he predicts the same forces would be aligned against it today. Farmers in areas where dairy farms are still expanding — such as South Dakota – always oppose production controls, Allbee noted.

"I suspect there'd be a lot of farmer opposition where there's a growth in production taking place," he says.

Congress did recently add about $1 billion to fund an insurance program designed to help farmers when milk prices fall.

Jacques Rainville says it might be easier for Washington to spend a big chunk of taxpayer money than adopt a Canadian system.

This story comes from the New England News Collaborative: Eight public media companies coming together to tell the story of a changing region, with support from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))