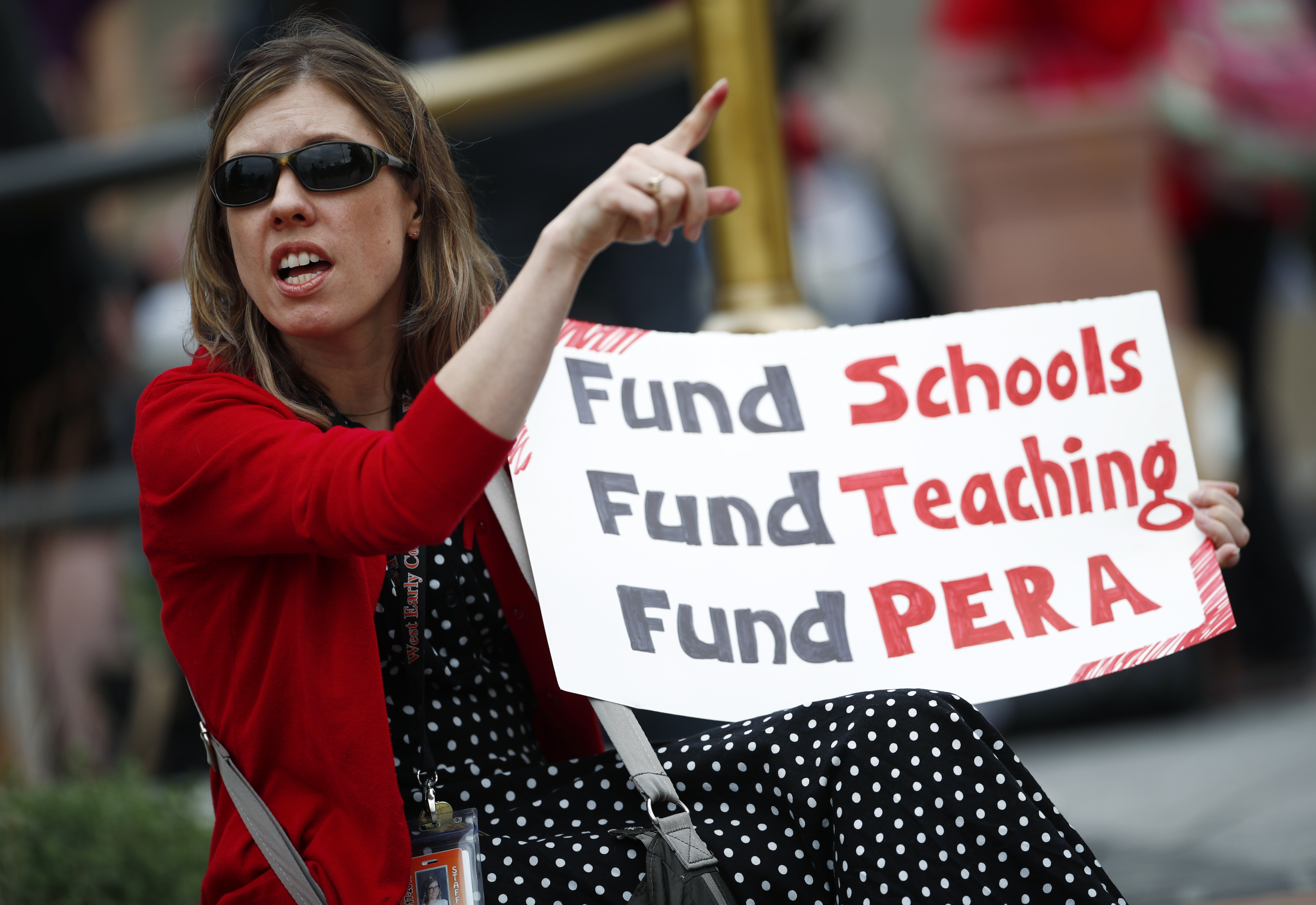

Just before midnight Wednesday, Colorado lawmakers passed a rescue package for the state public pension program that will have major ramifications for public sector workers, retirees and taxpayers across the state for decades to come.

The legislation aims to pay off the Public Employees' Retirement Association's $32 billion funding shortfall within 30 years, and calls for steep financial sacrifices from public sector retirees, workers and taxpayer-funded government agencies to do so.

The vote went down to the wire on the final day of the 2018 legislative session. After a day of frenzied negotiations and with support wavering in the Democratic-led House, Gov. John Hickenlooper made a surprise — and unprecedented in his tenure — late-night visit to his party's legislative caucus meeting to lobby for support.

On Thursday, he praised lawmakers in both parties for striking a deal.

"I think when you compare it to what other states have done it will be one of the most significant balancing acts of any state pension in the country," said Hickenlooper, a term-limited Democrat who leaves office at the end of the year.

Here's what you need to know about the final legislation, which on Friday afternoon still had not been published on the legislature's website for public inspection.

This was a nail biter.

The CO House has voted 34-29 for a plan to stabilize the state pension system, better known as PERA. Many Democrats, including Speaker Duran, voted no. #copolitics pic.twitter.com/sAgejpjH05

Why Was It Needed?

More than 566,000 current and former public employees are members of the pension system. That's roughly one in 10 Coloradans.

In 2010, the state legislature approved what was billed as a long-term fix to the pension, which was projected to run out of money after the financial crash of 2008.

Since then, the state pension board has steadily adopted more conservative financial assumptions. Retirees are living longer than previously expected. And because the last round of reforms were phased in slowly, government agencies continued to contribute less than is needed to pay for the benefits being promised to retired workers.

As a result, the pension's financial situation is among the worst in the country. The fund at the end of 2016 had just 58 percent of the money needed to pay off benefits.

It has a $32 billion unfunded debt by one accounting measure, $50 billion by another. And rating agency Standard and Poor's warned the state of a possible credit downgrade if the issue was not addressed this year.

What Do The Changes Mean For Public Employees?

Most public sector workers enrolled in the pension plan will contribute an extra two percent of their pay, phased in over the next few years, raising their contribution from 8 percent to 10 percent of pay.

Future employees will have to work longer, and their pensions won't be worth as much as prior generations because of changes to benefit formulas. Currently, state workers can retire at 60, and teachers at 58. The bill raises the retirement age to 64 for both.

The legislation allows more public sector workers to opt out of the pension and join a defined contribution plan, similar to a private sector 401(k). School district employees are still barred from doing so.

What Do The Changes Mean For Retirees?

The bill eliminates annual cost-of-living raises for two years, and then reduces them to 1.5 percent annually, down from 2 percent today.

Because pension recipients in Colorado don't pay into or receive Social Security, retiree pensions are likely to lose value over time to inflation, which has averaged close to 2 percent over the last decade.

For the average school retiree receiving a $37,000-a-year pension, the change equates to a $151,000 cut to benefits over a 30-year retirement, according to the pension system's analysis.

Before 2010, retirees received 3.5 percent raises each year.

What Will The Rescue Plan Cost Taxpayers?

The bill doesn't call for any tax increases. But it will require the government to spend more on the pension, leaving less money for public services.

Starting next fiscal year, the state will contribute $225 million yearly to pay down the pension's unfunded debts.

The state government and school districts also will contribute an extra .25 percent of payroll to the pension. Most public agencies today are already contributing 20 percent of pay. But very little of it is going to current employee benefits; the majority pays off unfunded benefits owed to retirees. Local governments were exempt from the contribution hikes, because their pension is better funded.

How Do These Reforms Differ From 2010?

Many conservatives still feel the reforms don't go far enough, but they do put some additional safeguards in place that did not exist in 2010.

Benefit cuts and contribution hikes will kick in automatically if the pension's finances veer off course. The bill also creates a legislative oversight commission to monitor the pension's finances more closely.