The concept of having “defensible space” against wildfires around homes in or near forests, scrubland or open prairie got a major test this week.

The situation looked dicey when the Buffalo Fire blew up between a pair of subdivisions above Silverthorne. But a decision years ago to cut down nearby vegetation and trees killed by beetles made all the difference for firefighters battling the blaze.

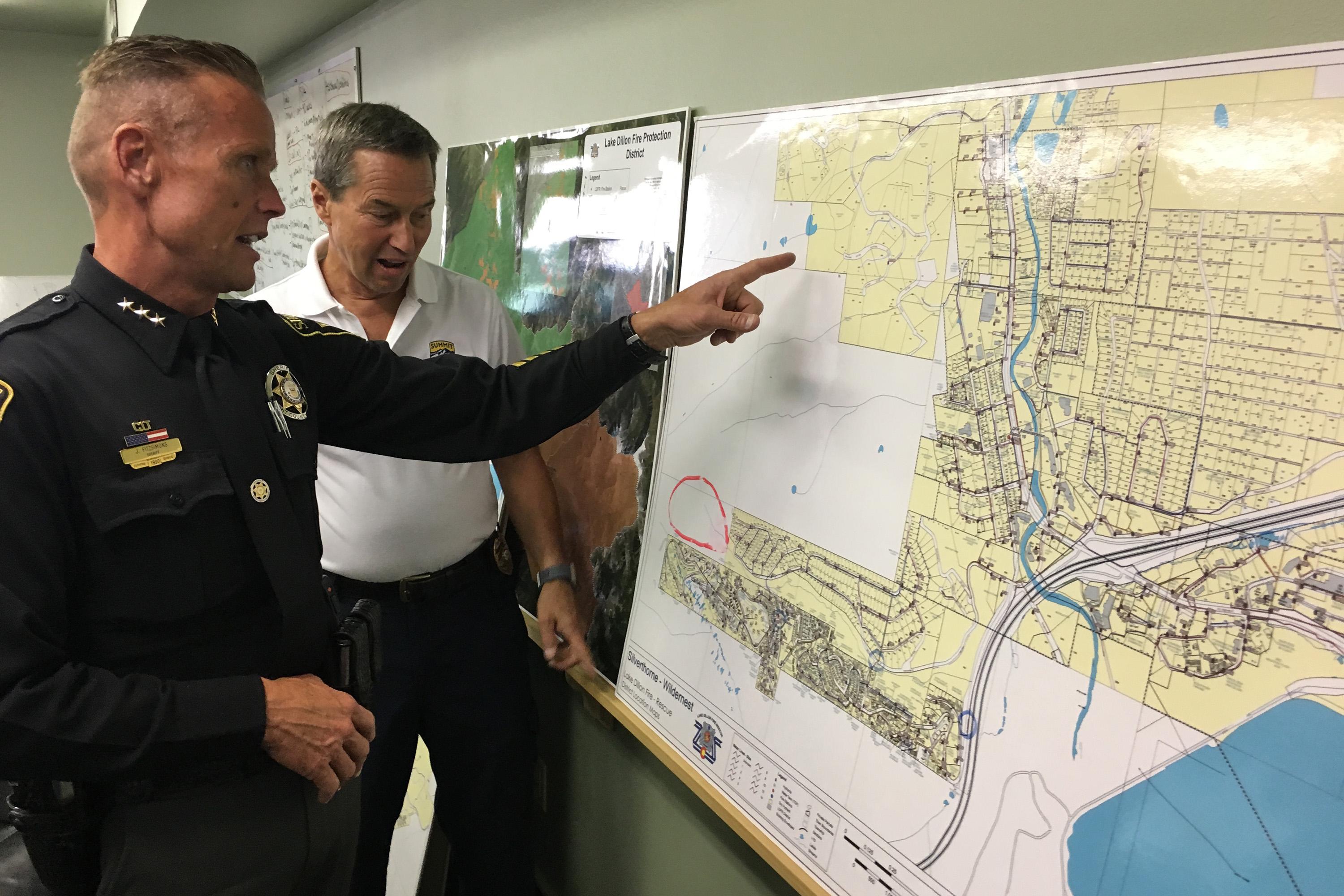

At the command center on Wednesday in Silverthorne, Summit County Sheriff Jamie FitzSimons looked at a map with the county’s Fire Chief, Jeff Berino. The focus of their attention: two densely-built subdivisions filled with condos and single family homes, just up the hill from town.

The fire made its way between the neighborhoods, just 250 feet from homes, and Berino worried that if it grew and turned and started burning into what he calls “garbage wood on both sides,” it could make a “significant run, make a run to Silverthorne, make a run to Frisco.”

Related Links:

- Wildfires: The Air Is Bad And It May Get Worse. Here's Where

- What Top Do Do If You Get An Evacuation Notice

- Department of Public Health and Environment Smoke Monitor

- EPA’s Air Quality Guide and Forecast Map

A dry spring, unseasonably warm temperatures, and days of gusty winds created an explosive situation above Silverthorne. And the Buffalo fire did blow up, doubling in size in the first 10 minutes to nearly 100 acres. Officials quickly evacuated nearly 1,400 homes in the area and called in air support -- firefighting helicopters and air tankers -- and more than 150 firefighters on the ground.

“It was a tactical nightmare right between two subdivisions. The good news is there were some clear cuts around them which bought us some time,” Berino said.

Clear cuts there created areas known as defensible space -- areas with no natural fuel for fires The Mesa Cortina and WilderNest subdivisions are adjacent to land controlled by the U.S. Forest Service and a few years back, out of concern for fire danger, the service cut 300- to 500- foot wide fire breaks in between the forest and the homes. Many of the trees there had already been killed by beetles.

“At the time, people were opposed to cutting down the trees,” he said.

Without the fire breaks crews would have been trying to save people’s homes instead of battling a wildland fire, and the results “could have been catastrophic,” FitzSimons said. The defensible space “gave us time, obviously, to evacuate people too.”

Up at the fire scene on Wednesday, at 9,600 feet, resident Janet White watched helicopters dump water from the sky as hand crews worked on fire lines and jumped to extinguish hot spots. A layer of red fire retardant coated the mish mash of stumps, branches and debris that the crews call jackstraw. Homes sat unscathed just a few hundred feet away.

“I saw the smoke and I thought it was gone. I thought we were gone, I thought this whole little area up here was burnt or going to be burnt,” White said.

The flames sent her into a scramble for a few possessions just before the evacuation order came. Her place is a few hundred feet from the fire. She and her husband had originally pushed for the fire breaks, worried a blaze here was inevitable, just a stray cigarette butt away.

“We breathed a sigh of relief when it was done because that was just a tinderbox.”

Her husband, Richard, says it was fascinating watching the crews feverishly work a blaze that surely could have destroyed their home, if not for the defensible space around the subdivision.

“If it had not been for the fire break these 200-300 homes would be gone,” he said.

The fire breaks saved this neighborhood this time, but the summer is just starting. Combine hot, dry conditions with wind and fire danger will be high for months ahead. That’s why Stage 1 fire restrictions will take effect for this part of the state: that means no campfires, campers must use stoves, and no personal fireworks.

On Thursday, FitzSimons announced the evacuation had been lifted.