For years, Principal Cyrus Weinberger thought a lot about everything he wanted in a school.

His mind danced with thoughts of hard sciences, biology, physiology and chemistry. But also, computer sciences, coding, robotics, artificial intelligence and virtual reality. And yet there was more. Movement, empathy for others and service.

“All of these pieces…. the more I dug into that, I realized there was a name for that and it was called neuroscience,” he said.

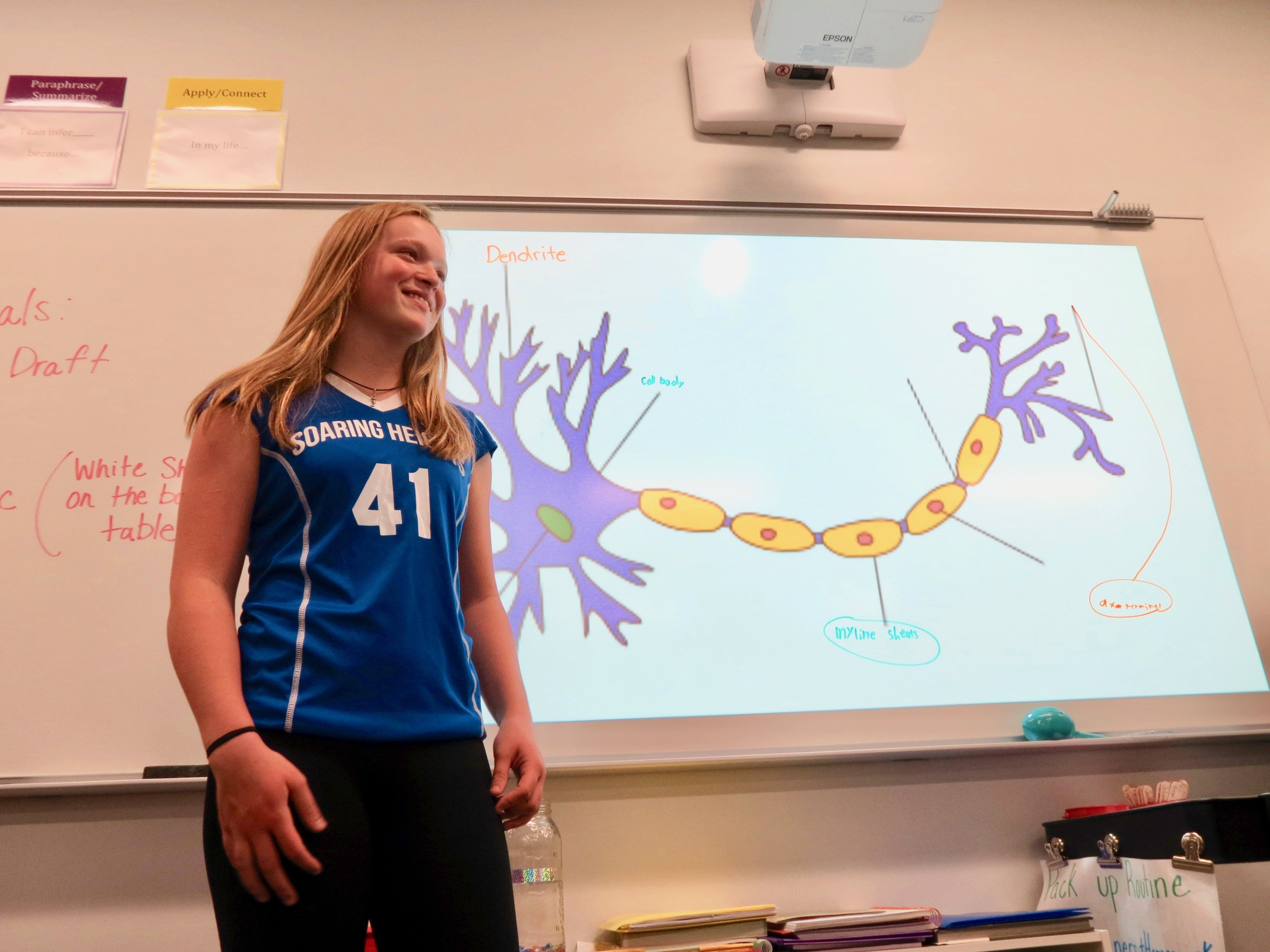

Weinberger wondered what a school that combined these things under one unifying concept would be like — and in 2016, something amazing happened. Voters in the St. Vrain Valley School District approved money to build the Soaring Heights PK-8 school in Erie, Colorado. The school opened this year.

Students at Soaring Heights learn everything kids at other schools do, but the STEM-focused school also uses principles of neuroscience to help students persevere, concentrate, unleash creativity, regulate their emotions and even develop empathy. They use the latest insights about how the brain works to inspire how the classrooms work.

Understanding how the brain works and adapts to stress, for example, increases self-awareness. In turn, that helps students navigate a test, go to a dance or understanding how their body works. It also helps with peer interactions.

“The more empathy and understanding that you have about what's going on in someone else's brain and why maybe they're acting the way they are allows you to interact in a much more meaningful and purposeful way,” Weinberger said.

An Environment Built On Neuroscience

It’s rare to experience what a new school looks and feels like. Especially one with an innovative twist. Everything from the architecture to classroom activities at Soaring Heights are grounded in neuroscience.

One the second floor of a cavernous open room, natural light streams through towering windows with Longs Peak in full view in the distance. Classroom ceilings are high; furniture is modern; walls can open and close. There are wobble stools, standing desks and skylights. There are two maker spaces, three science labs, four music rooms, two virtual reality labs, an outdoor garden and plenty of collaboration spaces.

Students digitally record and transmit morning announcements from the school’s well-equipped video room. And there are exercise bikes outside of some of the classrooms.

“If kids need to take a break or if they want to work and ride a bike, they can do that,” Weinberger said. “There’s a ton of research that correlates physical activity with brain development, attention, focus, attendance, fewer behavior issues.”

Teaching kids how the brain works is central to the school’s philosophy. Neuroscientists from Anschutz Medical Center created experiments to sprinkle throughout the curriculum. Sukumar Vijayaraghavan, director of the Neuroscience Graduate Program at the University Colorado’s School of Medicine, pitched throwing a ball into a basket. Then he said to put on prism goggles. Suddenly, you start throwing the ball at an angle.

“But what you also learn is that while you keep doing that, the brain will adapt and actually get you to the right place after a few trials,” he says. “So the idea that the brain is plastic and the brain can be trained to do stuff.”

When kids see that the brain can change and adapt it can be applied to learning challenges.

Learning About The Mind

Kids in one classroom see how a brain wave controls the body. Principal Weinberger and innovation teacher Anna Mills are hooked up to electrodes attached to a Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation machine. Mills thinks of lifting her arm. It lifts and in a split second, electrical currents pass into Weinberger’s arm which lifts automatically.

The students gasp.

“Does it hurt?” one student asked. “It doesn’t hurt, just feels a little funny,” Weinberger replied.

Just to make sure the adults weren’t tricking them, a student comes up to lift up teacher Anna Mills’ arm. With no brain waves passing electrical currents into Weinberger’s arm, his arm doesn’t move. The students are astounded and discuss real-world applications like prosthetic arms, driving a car, helping people with neurological disorders, and virtual network interfaces.

In another classroom, students are about to study how breathing and other sensory inputs affect the way the body responds to stress. A boy dons some virtual reality glasses and takes a harrowing roller coaster ride.

Kids cluster around him, iPads in hand, and measure his EKG before, during and after the ride. Sixth-grader Logan Knod sees that virtually reality “messes with your nervous system.”

Principal Weinberger believes understanding why and how people react is also the first step toward building empathy. Innovation teacher Anna Mills recalled one lesson where kids interviewed each other about what they find stressful. A big one was not having anyone to sit with during lunch, or play with during recess.

“The prototype that they came up with was a sensory buddy bench,” Mills said. “So they had a piece of lavender [kids] could smell and then a calming playlist to help the student feel less anxiety ... they were taking issues that they see everyday that are really important to them as a fifth- or sixth-grader.”

Sukumar Vijayaraghavan, of Anschutz’s Neuroscience Graduate Program, said he’s hopeful longitudinal studies on the school might reveal that that students have learned to demonstrate empathy for their pre-teen classmates who may be struggling as they embark on a roller coaster ride of new emotions.

“Looking at the mind as a product of something biological, it helps to demystify this whole process, which is for kids, very scary,” he said.

A Different Kind Of School

The real fun – and learning – is in the daily innovation time.

Students pick a challenge and design something; a play, a movie, a piece of art or an experiment. In two big makerspaces divided by age, students can glue and paint and saw. They can also use 3D printers, virtual reality and a laser cutter.

For seventh-grader Wesley Green, the chance be in a makerspace, rather than trapped behind a desk, is a relief to both body and mind.

“A lot of kids these days like to learn either digitally or they like to move around when they learn so they like to learn more physically, like hands on,” he said.

Even Kindergarteners, after reading the “Three Little Pigs,” designed their own houses and “used a blow dryer to see which design was the sturdiest,” Principal Weinberger said.

CU Neuroscience graduate student Jacki Essig said the ultimate goal of incorporating neuroscience into a school is to get students to think outside the box and practice critical and creative thinking.

“It's really just getting students to think, not just absorb information but to take that information and do something new with it,” she said.

Essig and CU Anschutz professor Sukumar Vijayaraghavan admit Soaring Heights makes them kind of jealous. They almost wish they were back in grade school. There was nothing like this school back in their day.