When it comes to participation in their children’s education, refugee families often face overwhelming barriers. The challenges run from teachers who speak a different language to incomprehensible rules and customs.

In the end, newcomer children often slip further and further behind their peers.

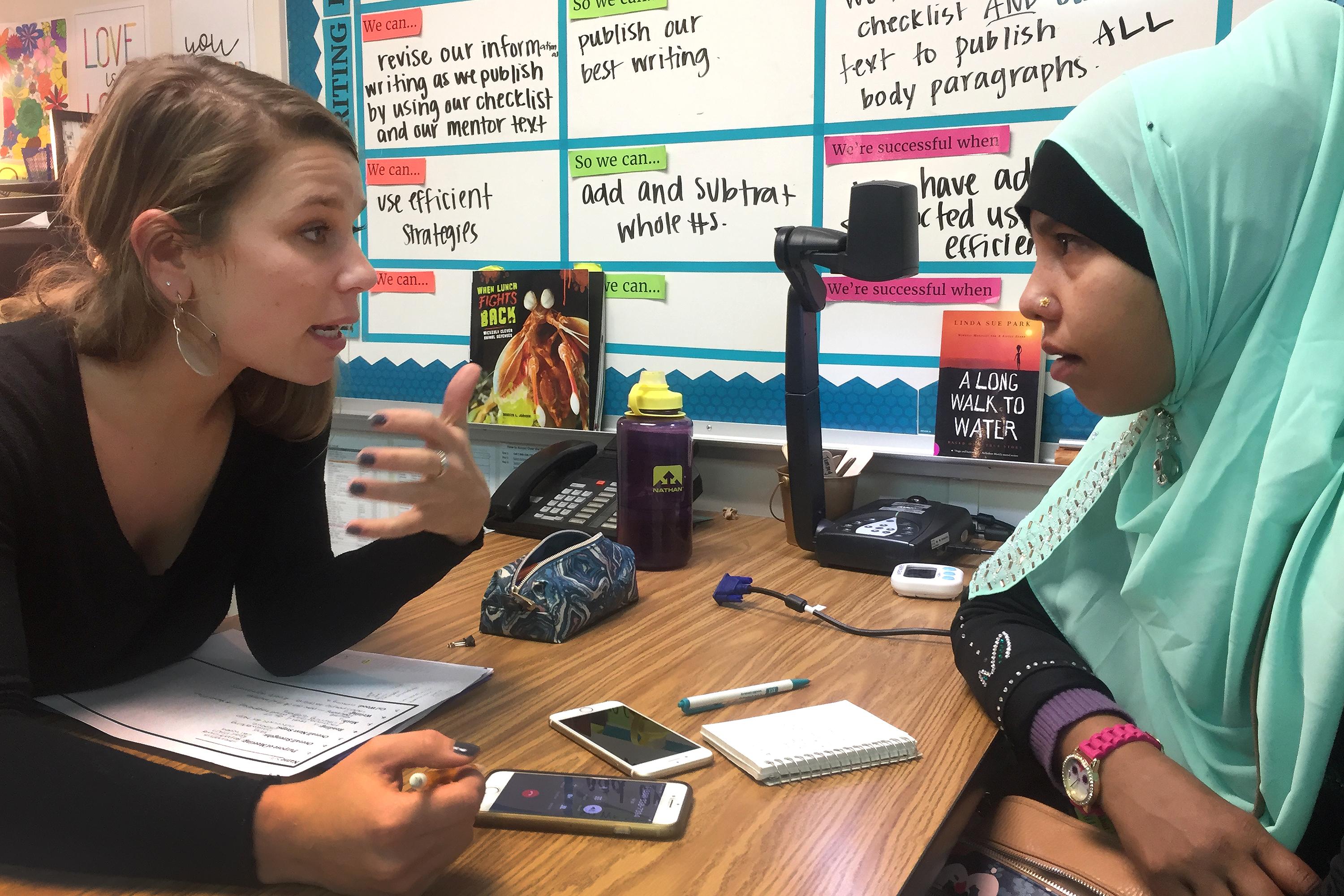

At Kenton Elementary — part of Aurora Public Schools — fifth grade teacher Gracie Binder is about to start her next parent teacher conference. First, there’s something she has to do. She needs to call for a Burmese interpreter.

The young mother in front of her is clad in an embroidered black dress, a teal hijab and in a Western touch, running shoes. Husanara Makbulhussin spent 13 years as a refugee in Malaysia as part of the severe repression of the Rohingya minority in Burma. Her family came to the U.S. in 2016. They now live in Aurora, Colorado.

Binder and Makbulhussin huddle over a phone as an interpreter comes on the line. Without them, they can’t understand one another. The parent-teacher conference started with Makbulhussin’s daughter Siti reading to her mother.

“I like to do writing because it’s my favorite writing,” Siti reads out loud. “I like to make more friend in the school.”

Binder interjects, asking the interpreter for a translation. It goes like this, haltingly.

The teacher told Makbulhussin her daughter is doing fabulous in school. Through the interpreter, she agreed when it comes to Siti’s reading and spelling, but said her daughter struggles in math. She shows the teacher a video she took of her daughter’s distress with a question. The translation comes through as “she couldn’t understand me. I couldn’t understand her … so she gets frustrated and is crying.”

In the video, a tearful Siti repeatedly erases her work and tries again. Makbulhussin knows this is her moment to push for what her daughter needs, to ask for more support.

Two years ago she wouldn’t have been able to do this.

That first day of school in a new country seemed exciting at first, but after a month Makbulhussin noticed a change in behavior. Her two school-aged daughters appeared deflated and depressed with a lack of energy. One day, Siti, the oldest, told her mother she didn’t want to go to school. Makbulhussin was crushed.

Siti, now in fifth grade, remembers how awful she felt. She was confused and didn’t know what to do. When the teacher asked her a question, she didn’t know how to respond.

Up until age eight, Siti had only a limited experience with school. In Malaysia, refugees weren’t allowed to work legally and their children couldn’t go to public schools.

Makbulhussin didn’t know what to do. It turns out, the teachers didn’t know the family had been in the country just four months. From that point on, her children received more support.

Becoming A Leader

Around the same time, Husanara Makbulhussin began her own journey after a friend introduced her to RISE Colorado.

“Families are the sleeping giant,” said Veronica Crespin-Palmer, RISE Colorado’s co-founder and CEO and currently an Obama Foundation fellow. “Once they’re awakened to the inequities that exist, the education system will never be the same.”

RISE works to empower low-income families of color, immigrants and refugees to push for equity in schools. They teach the skills families need to help their children academically. Crespin-Palmer is quick to point out that once they understand how to advocate for their children, participants “will change their life forever through education.”

Makbulhussin was one of the 1,535 families RISE Colorado has educated on a parent’s role in closing the education gap. It’s also trained 258 school staff on family engagement, race, equity and inclusion.

Once parents have some knowledge, they learn to push for district policies that help their children. Better translation services were at the top of the list. A 2017 RISE survey found 8 percent of Aurora Public School families received a report card in their language. Two-thirds weren’t aware of their child’s grades because of the language barrier.

This is where Makbulhussin kicked into gear.

It started with a school schedule that was in English, Spanish, Korean and Amharic. She didn’t see her language Burmese.

She asked RISE was there “anything they can do together to make it happen?”

Crespin-Palmer recalled Makbulhussin as shy at first. But at RISE meetings, she discovered her power and how to advocate. Makbulhussin spoke at school board meetings. She described her hopes and dreams for her children’s education and her experience coming to this country and navigating the education system with school board members, superintendents and elected officials. She also offered solutions.

“She was a force,” Crespin-Palmer said.

Makbulhussin and a team of refugee and immigrant parents lobbied for better translation services in Aurora Public Schools. Students in this district come from 130 countries and speak more than 150 languages.

If parents don’t see change, they start to shut down and confidence dwindles. But district officials were listening. Makbulhussin started getting phone calls in Burmese and official school papers came home in her language.

As Crespin-Palmer told it, she saw that she now had a “voice and people are listening. I’m stepping into my power and its working. I’m changing Aurora Public Schools. Not only for my three children, but for my neighbor, for my friend across the street, for the whole public schools community, so all of us have language equity and access to information about our children’s education in our native language.”

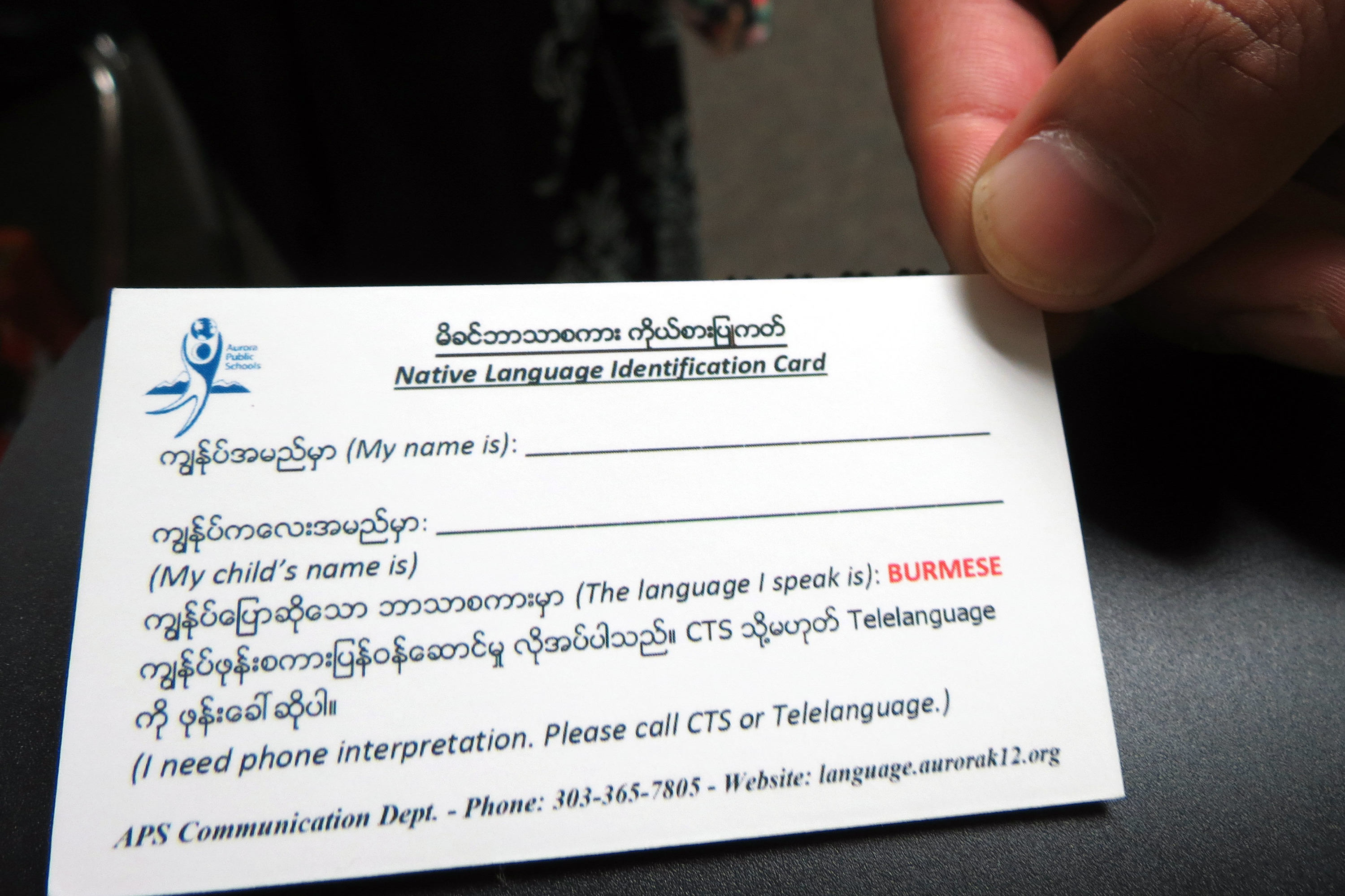

The school boosted the budget to create a centralized language services center, a one-stop shop for teachers and school staff to get help with interpretation. Parents now have language ID cards in the top 10 languages that helps parents get interpretation when they arrive at school with a question. The district passed a policy prohibiting the use of students are interpreters. So far, the district has met 11 of 12 requests of RISE family leaders.

Crespin-Palmer doesn’t believe they would have come this far without Makbulhussin.

Back At Home – And School

Makbulhussin doesn’t speak English, but she’s learned enough about the sounds and letters to help her daughters read. If they get stuck on a word she will type it into her cell phone. An app speaks the pronunciation out loud.

The teachers at Kenton are attentive and caring. Sometimes though, there are glitches. Teachers tried to translate the report card for Makbulhussin’s middle daughter Bivi with Google translate. They had the wrong language and they hadn’t yet learned that the district’s centralized language center could have helped with that.

Even with interpreters, in another language, everything takes more time. The teachers cleared up the misunderstanding and helped Makbulhussin install an app that allows the kids to document what they’re learning. Makbulhussin was gracious but wasn’t satisfied when she heard Bivi was behind in a few areas.

The teachers tried to reassure Makbulhussin that her middle child showed progress, but she pushed for more homework. RISE Colorado’s Veronica Crespin-Palmer said there’s a survival mentality many refugee parents exhibit.

“As a parent hearing your child is behind you go into panic mode of like, ‘well what am I doing wrong?’ We go into survival mode, like, ‘tell me what else I can do because I got to make sure they have every advantage of every opportunity and if there’s more I can do — give it to me.’”

Makbulhussin showed that same panic with Gracie Binder at their parent-teacher conference and the video of her eldest daughter Siti struggling with math.

In a soft voice, Binder told Makbulhussin to stop her daughter’s work if she finds her crying again, because “that should never be what homework is.”

Makbulhussin started to cry in front of the teacher because it’s hard for her to relax. Stress and feeling of lost control are common in refugee parents. At the same time, Crespin-Palmer said these same parents “are powerful, resilient and courageous, and Husanara embodies all of that.”

Makbulhussin collected herself and Binder then explained an approach to the math problem that will help Siti out.

The fifth grade teacher then returned the conference to what it was intended for — a celebration of how far Siti has come. Makbulhussin’s oldest daughter is showing good academic growth.

Binder saved the best for last. She described Siti as “kind, hardworking, friendly and creative.”

“You have an amazing daughter Husanara,” Binder said.

Makbulhussin smiled and headed for the next parent-teacher conference. She has another hour left at the school. She told the teacher for her youngest daughter how Siti helped her middle sister with homework and how the youngest daughter in turn helped out the oldest. But it doesn’t stop there. She told the Kindergarten teacher about how all the daughters help their parents with their own kind of homework: learning to speak English.