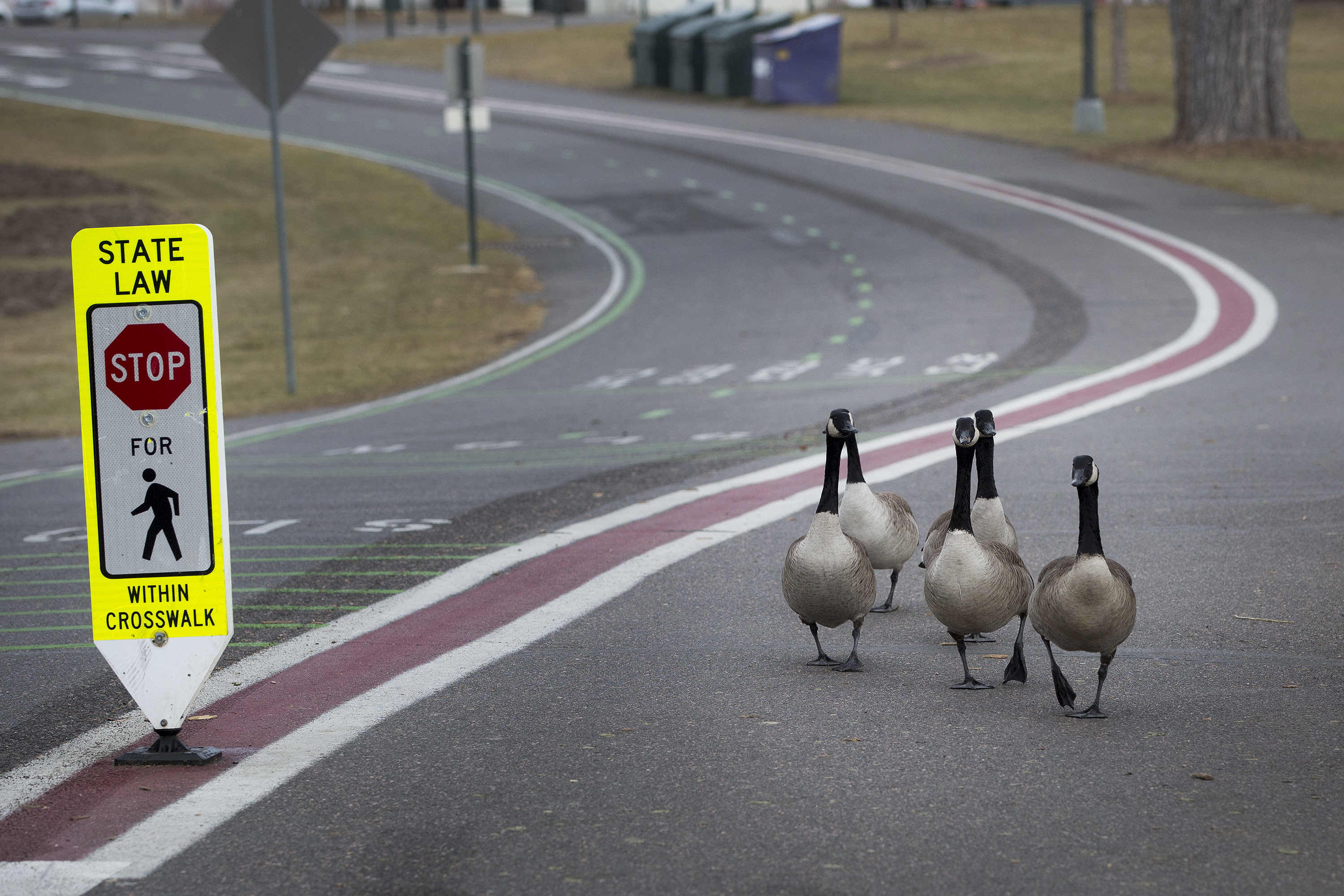

Hundreds of thousands of Canada geese flock to Colorado every year and Denver has fast become one of their favorite places to roost. Like most who move to the Centennial State, they’ve identified a plethora of reasons to post up in Denver.

Dave Stuart, like his avian transplant-brethren, hails from the northern United States. When he moved here from Minnesota three years ago, he was astounded by the sheer number of geese that blanket the city. His question for Colorado Wonders: Where are all these geese coming from and why are there so many of them?

Do We Have A Lot Of Geese?

The short answer is yes, but we didn’t used to.

In the early 1900s, the Canada goose population was nearly eradicated across the nation and Canada because of overhunting. In the 1950s there was a combined effort throughout the states to bolster goose numbers by placing goslings and eggs in areas that were habitable.

“If you release young geese in an area where they can successfully live, they get attached to that area,” said Jim Gammonley, the avian research chief for Colorado Parks and Wildlife. “They stay there, they nest there, their young come back to that area and nest.”

And so, the goose gentrifiers grew from a couple of hundred local geese in the ’50s to nearly 5,000 by the mid-’70s. Growth has slowed, but today the Canada goose population has doubled.

In many instances Gammonley said we’re coming to them — not the other way around.

“Remember, back in the 50s and 60s there was a lot more rural country up and down the Front Range that had good habitat for geese,” he said.

The sizeable resident goose population is stable. The migrant goose population, on the other hand, has seen exponential growth.

Each winter an average of 180,000 geese descend on our state, Gammonley said. The word is out among the birds: Denver is legit. When the geese start south, hundreds of thousands of them have Colorado in mind. And because Canada goose are very site faithful, they tend to migrate to the same place every year — with grandma, grandpa and creepy uncle Carl in tow for the entire holiday season. Some even stay for good because they’ve found love in the eyes of a local (Parks and Wildlife says don’t feed the birds) or they can’t get enough of the beautiful mountain views or the swanky parks.

Is Climate Change Affecting Goose Migration?

Colorado weather is getting warmer, bit by bit.

“Currently, 1954 to 2017, there’s been an increase of average temperatures by 0.4 degrees Fahrenheit per decade,” said Klint Skelly, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service in Pueblo. “Looking at the data it does have a pretty distinct upward trend, 0.4 degrees a decade which is quite a bit if you think about it.”

Those numbers are rough estimates and while a higher average temperature might equate to lakes freezing later or thawing quicker, Skelly doesn’t think it affects the geese. Gammonley agreed.

“Birds up in Canada will stay there until weather drives them out and then they tend to go just as far as they need to,” Gammonley said. “So, if we have a mild winter a lot of those geese will stay well north of us until very late in the winter before the majority of them make it down here.”

Warmer temperatures in cities do affect where geese will roost and whether or not the will leave. Garth Spellman, the curator of ornithology at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science, called this the urban heat island effect. Temperatures in city centers tend to be higher because the buildings create something of an impenetrable area where you have asphalt and other dark surfaces that heat when exposed to the sun and retain that energy.

“So even in our deepest winter, in our coldest times, the City Park lake, Ferril Lake, stays open for most of that year,” Spellman said. “Most of the year, it might freeze over for a couple of days, but they can hold on for a short period of time. And so it makes it a quite accommodating area for these geese and they’ve chosen not to migrate because of it.”

Why Do The Geese Like Our Parks So Much?

Vicki Vargas-Madrid, the wildlife specialist with Denver Parks and Rec, has watched the geese numbers burgeon over the years.

“It’s the habitat that we provide for them, which is mowed green grass, water features, open areas where they have the view of their surroundings and not enough natural predators to keep their populations down,” she said.

Like everyone else moving to Denver, it’s all about location. For a goose, water is the most important factor when deciding where to settle. Geese roost on water at night and in a dry state like Colorado, that immediately starts concentrating them in certain areas. During the day they won’t wander too far from water. It’s why you see relatively large groups at places such as Wash Park or City Park and far fewer at Cheesman or Southmoor parks. They can be seen in those parks to eat, but they will head back to parks with water features each night.

Gammonley said Canada geese are also pretty darn smart.

“Once the hunting season gets going and the geese get down here, they learn fairly quickly that if they move into town they can avoid being hunted and so we get concentrations of birds in the city,” he said.

While eastern plains geese are prime targets during hunting season, the city geese are very well protected. In fact, they have legal protection; it’s against the law to harm a city goose. That’s just reminder, since not everyone is a park goose fan.

“They’re annoying and gross,” said City Park resident Ashley Marsh. “They honk so loud you can’t even sit in the park in peace and there is poop everywhere. They poop on my car, my dogs eat the poop, you can’t avoid it. It’s disgusting.”

In the way of goose complaints, Vargas-Madrid said poop tops the list. In fact, geese are so prolific that the daily routine of park maintenance staff includes sweeping up goose waste. A Canada goose can eat up to four pounds of grass each day and will deposit an average of two pounds right back onto it. And in case you were wondering, a goose poops about once every 12 minutes.

Hazing is the most effective way to get geese to “move along.”

“So what we use is a machine called a goosinator,” Vargas-Madrid said. “It’s a big, huge, foam looking like type of machine that looks like a predator. It’s painted in fluorescent orange color with an ugly face painted on it to scare the geese and we use it to haze the geese off of our park properties.”

This method takes some time. Canada geese typically have to be hazed multiple times before they decide to find other places to hang out. Parks can also alter their landscapes with taller grasses, which break up a goose’s line of sight, or they can mow less often, making it a less desirable place to be.

However, many park-goers aren’t ready to brand the geese as a nuisance. Karen Trierweiler and Karen Osthus rather enjoy their walks through Wash Park where geese — and their poop — abound. They acknowledged that dodging the poo can get old, but not seeing the birds would be strange.

“You’re just used to them if you walk in Denver parks,” Osthus said. “They’ve been here for so long that they’ve just become a part of the landscape. I think the geese and the people have found a good balance and they’re pretty.”