Mark Dorrance has been driving trucks in the Denver area for about 40 years. One common route takes him to the Magellan pipeline terminal in Aurora, just south of Interstate 70 off Chambers Road.

"I've been there thousands of times,” said Dorrance, an employee of Wyoming-based Dixon Bros., Inc.

Around five years ago, Dorrance noticed something just north of the terminal: Construction crews were laying tracks for the Regional Transportation District’s A Line train from Union Station to Denver International Airport.

"I thought, 'Well, this is going to be a traffic nightmare,’“ he said from the cab of his truck on a sunny December morning.

- RTD Is Fixing Its Commuter Rail Cars. The Issue Could've Been Worse

- A Pocket Guide To All Your Questions About RTD’s Ongoing A Line Drama

That prognostication has proven to be correct, at least in the eyes of Dorrance and other hazardous material truckers. When drivers leave the Magellan terminal with 8,500-gallon tanks of petroleum and turn north on Chambers Road to get back to Interstate 70, they have to come to a complete stop before crossing the A Line tracks. That leaves half their rig blocking traffic in the busy intersection. The frequency of A Line trains — they pass every eight minutes or so — further complicates the situation.

Hazmat trucks cross the tracks between 600 to 1,000 times a day, according to the Colorado Motor Carriers Association. The Federal Railroad Administration has described the crossing as “high risk.”

"I'm just scared of the day that a car goes under a tanker — or worse yet, a train and a tanker collide,” said Dean Teter, senior safety director for Dixon Bros. “It's going to be pretty catastrophic."

While Chambers Road isn’t a designated hazmat route, it is the shortest, most direct (and therefore preferred by state law) route between the Magellan tank farm and I-70. Truckers worry if they deviate from the route they’ll be held liable for any accidents that occur off the route.

Beyond that, any problems at the Magellan pipeline terminal could have a big ripple effect. The fuel from there goes to gas stations up and down the Front Range, and to DIA.

“If you were to cut off access to Magellan pipeline terminal, you could see bags on stations and stations running out in a fairly short order,” said Grier Bailey, executive director of the Colorado Wyoming Petroleum Marketers Association.

Bailey, along with the Colorado Motor Carriers Association, have pushed RTD, the city of Aurora, and other governmental agencies to come up with an alternative that would direct hazmat traffic away from Chambers Road. Greg Fulton, president of the CMCA, said he brought his concerns to RTD shortly after A Line testing began in 2015.

“I don't think I know of anywhere in the entire country where we have a commuter rail line carrying this volume of people built over a crossing with a hazardous material route like this,” Fulton said.

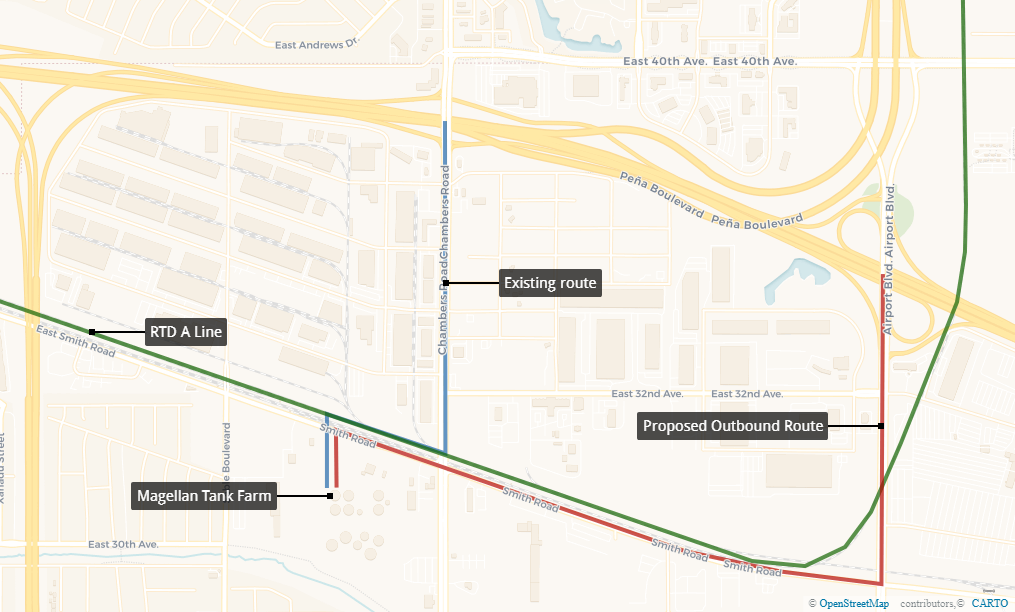

RTD, with the FRA’s encouragement, convened a series of meetings in late 2017 resulting in a draft report that recommends shifting outbound hazmat traffic to nearby Airport Boulevard. There’s no A Line crossing there; the train flies over the road as it turns north to DIA. That route may require infrastructure improvements, but the draft report doesn’t estimate a cost and doesn’t say which entity should pay for them.

“We appreciated the effort,” Fulton said of the study. “Unfortunately,” he added, “it's one that doesn't truly make sense.”

Joe Christie, project director for RTD’s A, B and G lines, said the agency has stepped up and commissioned the report, which is still being finalized. “We’re trying to address everybody’s concerns,” he said.

But, Christie said, the truckers brought their objections far too late in the process. The right time for those was back in the 2000s, he said, when the A Line project went through a major environmental impact study. He said RTD sent notifications to every business along the A Line corridor and held many public meetings.

“We didn't hide anything about the A Line from the public,” Christie said.

The Colorado Public Utilities Commission signed off on the crossing back in 2013. But PUC spokesman Terry Bote said RTD did not mention the heavy volume of hazmat traffic in their application. Asked whether having that information would have changed anything, Bote replied, in a statement, “That's not a question that can be answered. I can't guess on what a PUC decision would have been based on unknown information.”

He added: “the appropriate safety measures have been put in place.” The federal regulator, the Federal Railroad Administration, is partially closed because of the government shutdown and did not respond to a request for comment.

RTD’s Christie said passengers should feel confident in the A Line. “We strive for the highest level of safety possible,” Christie said.

The A Line is a good thing for Denver, the CMCA’s Fulton said, though he noted the line’s well-documented crossing gate troubles bolster his case. Mostly, he said, he wants truckers to be as safe now as they were before the A Line opened, adding that the situation is far riskier than it should be.

“I don’t ride the A Line,” he said. “And I don’t encourage my family to at this time.”

All the entities involved, including RTD and the city of Aurora, say they are still working together.

“Our goal is to work with all parties involved, find solutions and to maintain flexibility in routes that make the most sense for everyone based on location,” city of Aurora spokeswoman Kim Stuart said in a statement.

“Something has to be done,” added state Rep. Dominique Jackson, D-Aurora. “And I would agree that something has to be done relatively quickly.”

But a key hold up is determining who will pay for improvements; Jackson said it would be “highly difficult” to find state funds.

So in the meantime, trucks will keep crossing the tracks — hundreds of times, every day.