Back in 2005, Denver Public Schools became the first large urban school district in the nation to experiment with an incentive pay system. Bonuses, for example, are awarded to encourage teachers to take hard-to-staff positions, placement in high poverty schools or high priority challenged schools.

Before long, the system became unwieldy, complicated and unpredictable — and now lies at the core of the dispute between Denver teachers and the district.

With both sides poised to meet on the cusp of a strike, the question is can the incentive system be reformed to drive the results DPS wants and ensure the financial benefits teachers seek?

Public bargaining session between @DenverTeachers and DPS, 5:00 p.m., 1617 S Acoma St, Denver on Friday. Union says teachers are preparing to picket/strike Monday at 7:00 a.m. #edcolo #coleg #copolitics #teacherstrike pic.twitter.com/YaEcBUbhNI

So far, both the union and district have streamlined incentives and made some of them more reliable. But the one of biggest gaps between the district and the teachers remains the amount paid for high poverty schools and the $2,500 incentive for teachers at the district’s 30 “high priority” schools.

These Denver schools have significant academic challenges, high concentrations of students living in poverty and many English language learners.

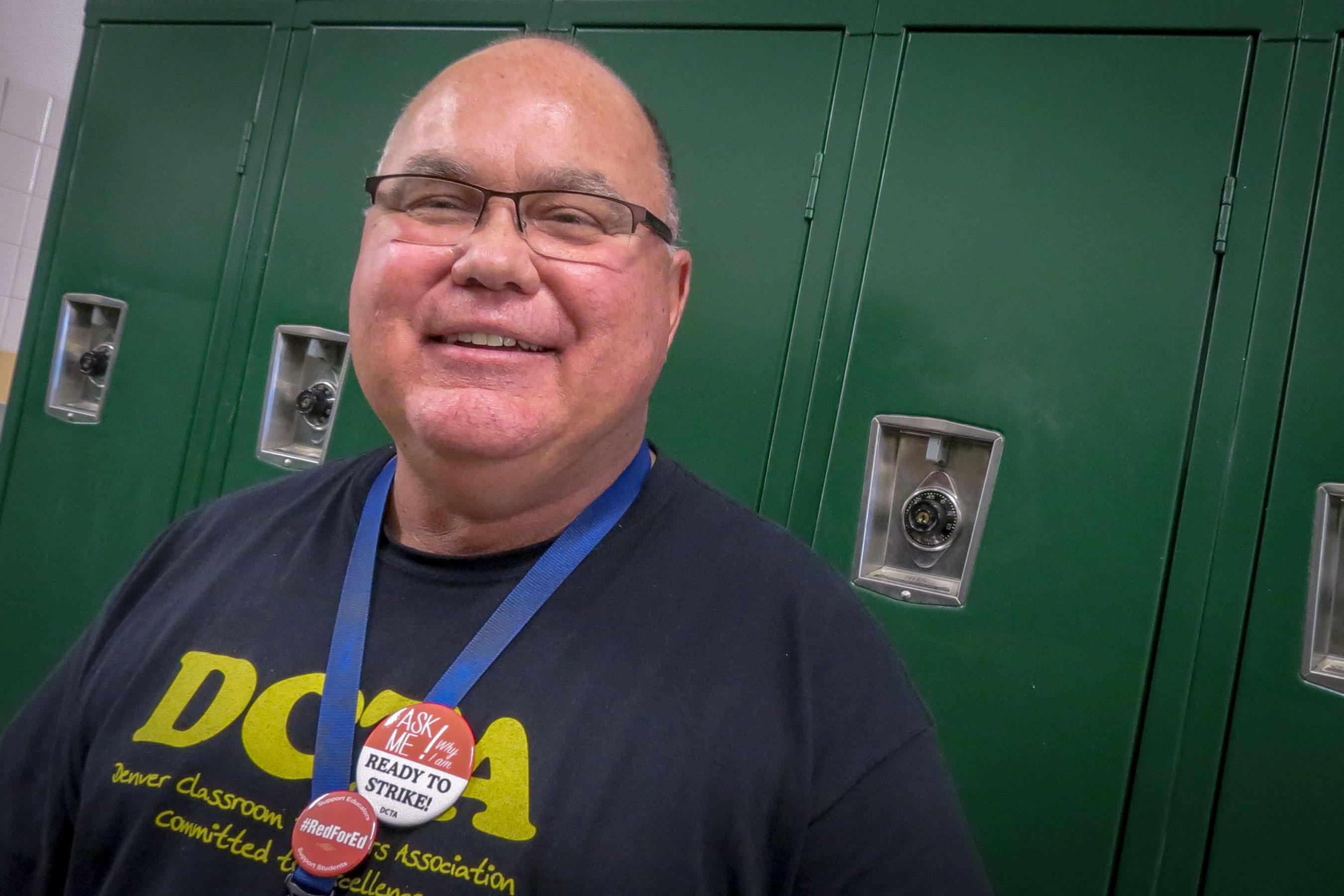

Joe Waldon, a social worker at Skinner Middle School, acknowledges he’s benefitted from the incentives. Back in 2011, then-superintendent Tom Boasberg gave one of those giant commemorative checks to the staff. The total on the check was $233,711.58, the amount of incentive pay earned by Skinner teachers.

Waldon was happy. As he said at the news conference with Boasberg and that big check, the incentives reward “me for my hard work when we see results with the kiddos.”

That was more than seven years ago. Today, it’s a different story and Waldon’s incentives have undergone many twists and turns. Skinner teachers used to receive a monthly bonus for serving in a school where more than 75 percent of students qualified for federal free and reduced price lunch.

At the time, Skinner was struggling and on the brink of closure. But gentrification in Denver’s Highlands was just ramping up. Waldon said teachers worked hard to regain the community trust and attract children from the affluent families that filled the trendy neighborhood.

The school’s population doubled and Skinner fell below the high poverty threshold that qualified teachers for the incentive. That meant Waldon “basically took a salary cut of $206 a month,” he said. Other incentives came and went as standards and the school changed.

The fortunes of Skinner Middle School improved, but for Waldon, “it really felt like a slap in the face in regard to we’ve met the goal and now that we’ve met the goal, we’re going to take away the reward that we were giving you for trying to achieve the goal and that didn’t feel good.”

The teachers union wants to scrap the $2,500 high priority incentive and has offered $1,750 for the high poverty schools, with the difference poured directly into teacher base salaries. The district is adamant the $2,500 incentive is critical to teacher retention in these schools. DPS said their data has shown a 4 percentage point increase in retention since that incentive started.

Before she was the Denver superintendent, Susana Cordova was a principal at a high priority school, so she’s acutely aware of the teacher recruitment challenge. Some teachers even agree that the incentives should remain. Rhonda Jackson, an African-American special education teacher at Hamilton Middle School, worries that high priority schools that primarily serve students of color will lose effective teachers if the bonus goes away.

For her, the bonus “is a deciding factor in attracting quality teachers” to schools in northeast Denver.

Jackson receives an incentive for teaching at a high poverty school. Her colleagues at other high priority schools, some of which are even more challenged, have told her if they lose the incentive, they’ll move.

“We’re talking about already underserved schools and we’re talking about positions that are already understaffed,” she said. “So, immediately I think that’s going to have a huge effect on these schools in these positions.”

Part of Jackson, however, dislikes the incentives. She’d prefer teachers at schools with big academic and social challenges get a higher base salary.

Alison Corbett, a high priority school educator, said teachers work there for the right reasons. But if they see a monetary acknowledgement of the huge challenges in their work, there’s more of a reason to stay.

“If you could make the exact same amount of money at a building where there are less challenges versus at a building then there were there more challenges than other than a moral purpose, it [the incentive] helps the teacher make that decision,” she said.

Corbett said their most of their highest quality educators have stayed since the bonus started. A soon-to-be-published study from the University of Colorado Boulder backs up those claims. Study author Allison Atteberry said the data reviewed between 2000 and 2016 suggests teachers who rate more effective are leaving Denver half as fast as teachers rated as less effective.

“While we don’t see any evidence that teachers are moving into these kinds of schools we may see some evidence that they are staying so they’re making decisions to stay in those schools,” Atteberry said.

The effect of the size of the bonus wasn’t part of Atteberry’s study. However, a national study and a separate study in Washington D.C. both indicate that incentives in the range of $5,000 to $10,000 do have an appreciable effect on teacher recruitment in challenging schools. Those cash figures are much higher than what Denver’s incentives are.

“I think teachers are already working pretty much as hard as they can,” Atteberry said. “Instead, the more promising way financial incentives to have an effect is by acknowledging and valuing the hard work teachers are already doing.”

A strong body of research suggests that school culture, environment and leadership are reasons why teachers stay. One study suggests that any benefit that comes to retention through incentives is overcome by those more important factors.

DPS has said more than half of teachers surveyed in high priority schools said the incentive influenced their decision to stay.

Morgan Mendez wasn’t one of them. She taught in a high priority school that was about to close. She said the children were demeaned, there was no library and teachers weren’t held to high standards.

A $2,500 bonus wasn’t enough to keep her there.

“Good leadership keeps people there,” she said. “Equity, one of our core values, would keep people there. Integrity would keep people there.”

Prior the arrival of Principal Felicia Manzanares in 2016, there was lots of leadership turmoil at Cheltenham Elementary, a high priority school, which caused many teachers to leave. Many students there are children in poverty, who have experienced trauma and have mental health issues that play a big role in their ability to learn. Cheltenham students are among the districts most vulnerable.

All Manzanares’ teachers appreciate the bonus. As the strike approached, about half of the staff told her they’d still be there without it.

The other half of the teachers are there for the same reasons, but are fiscally aware. They come to the principal with their calculators and tell her the incentive is very important and remind her that “Denver is not an inexpensive place to live.” Manzanares is afraid she may lose some of those teachers if the incentive goes away.

She believes all teachers should have a competitive salary. But what all her teachers would argue, she said, “is the work is not the same in a high priority school. It takes a toll on teachers’ personal lives.”

“We all have hurdles no matter who we serve,” the principal said. “[But] the work is harder in our school. It just is. It is remarkably different in this building than it is in schools that are just blocks from us.”

Manzanares believes the dispute over incentives asks teachers to pit their work against each other. “We don’t want to say that we’re better than anybody else or that we work harder than anybody else, and I’m not saying you’re better, but I’m saying you’re committing to harder work.”

Atteberry, the CU Boulder researcher, said that a confluence of factors means that, in a way, everyone is correct. Skyrocketing home prices and low teacher salaries both added fuel to the labor dispute. It can be true that for most teachers the incentive system is broken and for others in a limited number of select schools, some of the bonuses worked as intended and teachers felt rewarded.

Atteberry noted that the perfect storm has led to DPS teachers’ very real experiences with compensation and the current standoff. Teacher retention has dropped overall in Denver and Colorado as has the number of people entering the profession in the first place. At the same time, this is a labor market with a huge demand for teachers and Atteberry said that one study shows the state ranks last in the nation for wage competitiveness.

“Given the confluence of factors, I think that uncertainty [of bonuses] is particularly painful for teachers,” she said.