Denver’s teachers union is wielding one powerful weapon in its strike against Denver Public Schools: growing membership.

For years, only about half of eligible educators chose to join the Denver Classroom Teachers Association. The union in Jefferson County was bigger, even though the district is smaller.

But in the last two years, Denver union officials say, membership has swelled to 3,800. That means 72 percent of eligible teachers, nurses, counselors and others are now choosing to pay $70 a month to belong to the union.

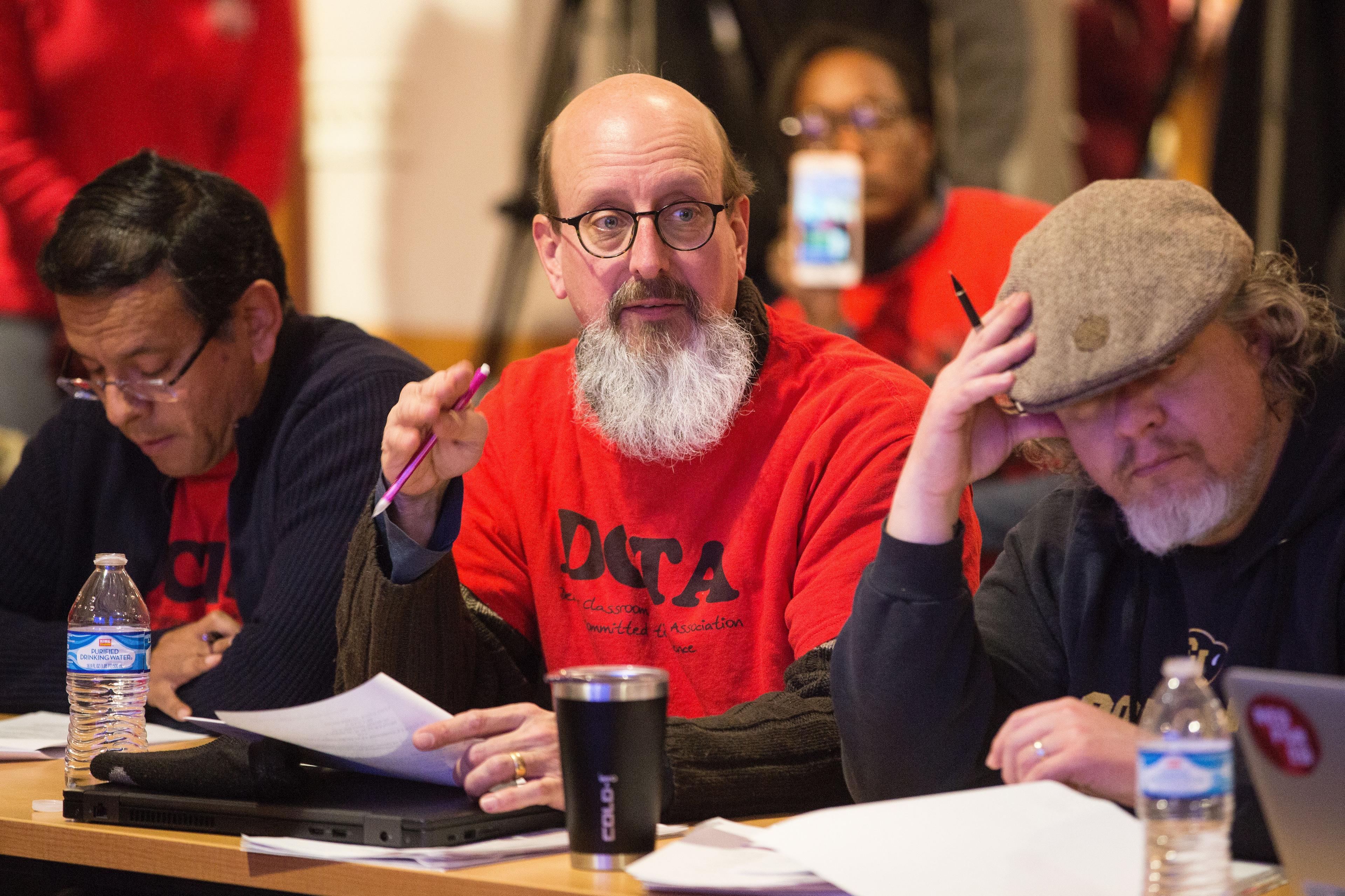

The membership surge makes DCTA the largest local teachers union in the state, president Henry Roman said.

Many forces have coincided with the membership growth, including the union’s pay dispute with the district that is the immediate cause of the strike, a national teacher activism movement, and a U.S. Supreme Court decision that both threatens unions and gives them new opportunities to organize.

Locally, an internal caucus has for years been pushing the Denver teachers union to be more aggressive and progressive in an effort to attract younger members. That effort has paid off, according to educators who have been with the district for decades.

“I’ve seen a resurgence in the union being a very popular thing for younger teachers,” said Dave Hammond, band director at Denver School of the Arts for 25 years. “It was always there but not as strong as it is now.”

Union leaders have ramped up efforts to get Denver teachers to join, adding a staff member whose job is to work with teachers in “innovation schools” and dropping indications that it might begin engaging educators in non-unionized charter schools.

In recent weeks, as a strike grew increasingly likely, Denver union leaders emphasized that only members could vote on a strike — and then made it possible to sign up on the spot as the vote was taking place. Union officials said 250 teachers had joined that way.

One big test for the expanded membership is the degree to which members participate in the strike. So far, the numbers from the district and union haven’t made that clear.

The district reported Monday that 2,631 out of 4,725 teachers — or about 56 percent — didn’t show up to work. That would represent 70 percent of the union’s current membership.

The union challenged the district’s numbers on Monday, saying that 3,769 out of 5,353 Denver educators — not just teachers but also school nurses, counselors, and others — were on picket lines on Day 1 of the strike. That would have put strike participation at 100 percent of union membership. (Some non-union members may have decided to join the strike.)

At Chalkbeat’s request, the district Tuesday provided a revised count for Day 1 that included those nurses, counselors, and other “special service providers” — and it rose to just 2,791. A spokeswoman cautioned the numbers may not provide the full picture because those staff were prioritizing support for students with special needs over reporting their own attendance.

The union and district haven’t yet offered participation numbers from the strike’s second day.

The murky numbers have drawn attention from longtime observers of teachers union dynamics. Mike Antonucci, a self-appointed watchdog who frequently criticizes teachers union leaders, wrote on his blog that the participation rates in Denver’s strike stand out.

“This divide is a significant difference from the other walkouts,” Antonucci wrote. “We should know more about it.”

What is clear is that the strike could help the union continue to grow, particularly if the ultimate deal reflects the union’s goals.

“Teachers unions are striking and winning. It provides a very viable way to show members, we have value and we can win,” Bradley Marianno, a professor at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, who studies teachers unions. “If successful, this type of activism can really rally members.”

Sarah Darville contributed information to this report.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news site covering educational change in public schools.